How to Study Shadow Curators? Biases in the YouTube Algorithm

It is getting harder to pinpoint the interferences when it comes to our experience in digital media. We are constantly living under the flood of content the internet has to offer, never really realizing that our choices are being manipulated by human and non-human actors. So how do you really study the shadow curator that is the YouTube algorithm?

Introduction

In the field of new media research, various collective phenomena can be explored by different means of investigating the digital traces found on online platforms. Digital methods is a research approach that makes use of the engravings provided by digital platforms and repurposes them in order to explore a specific digital media object. The strength of digital methods lies in their ‘’capacity to take advantage of the data and computational capacities of online platforms’’ (Venturini 4195). When studying a digital object, however, it is a challenge to separate the phenomena arising around the object from the features of the platform that they arise in. In his article ‘’A reality check(list) for digital methods’’, Venturini proposes a number of measures that can be used as a checklist in order to deal with these methodological difficulties (4221). These measures consist of defining the object of a study and reflecting on its manifestation within the medium that it arises in, aligning the relation between the object of study and the research question, and checking whether this process is attuned to the formats and the user practices of the medium, investigating whether the phenomenon you are studying spills across different media and demarcating the digital findings. Digital methods have been used by various scholars in researching digitally traceable social phenomena. It would be challenging to ask ourselves whether digital methods and Venturini’s guidelines would be fitting in order to put a nonhuman phenomenon under the researcher’s lens.

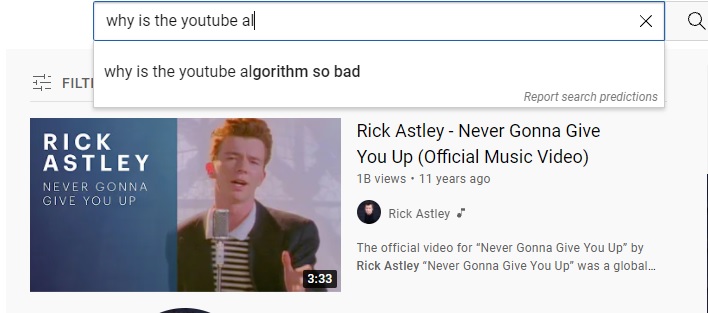

The Object: YouTube’s Search Algorithm Bias

For the purpose of this study, the nonhuman object chosen for discussion through the lens of the difficulties of doing digital methods is the bias of the YouTube search algorithm towards marginalized creators. In order to understand why carrying out research about algorithms may be problematic, we would have to be able to explore the nature of the algorithm that would help us demarcate the phenomena of bias more clearly. When conducting research about algorithms from the perspective of new media studies, scholars might be tempted to view them as mere products of technological applications. However, as Gillespie states: ‘’Algorithms need not be software: in the broadest sense, they are encoded procedures for transforming input data into a desired output, based on specified calculations’’(67). Whereas the end-users may experience algorithms as a simple and integrated feature, the database and the algorithm can be treated as distinctive elements since ‘’Before results can be algorithmically provided, information must be collected, readied for the algorithm, and sometimes excluded or demoted.’’ (Gillespie 74) In a database created by supposedly independent publishers, and claims to be ‘’open for everyone’’, this distinction between database and algorithm becomes more visible and important since the algorithm is created by the platform itself. Although YouTube representatives seemingly introduce key indicators such as retention and watchtime for the sake of transparency, these statements provide little information on how different types of metadata work and their importance in the algorithmic process. (Southern)

How To Best Apply Digital Methods to the Object?

The YouTube search algorithm has been studied and researched by many scholars in terms of bias. Because the algorithm itself is not openly shared because of economical implications, it is to an extent inevitable for scholars to focus on the outcomes of the algorithmic data rather than speculating how the algorithm works only through the statements by the platform. Since the platform is most likely to share the changes in the database that will help the company building an image that will help enhance the platform’s political economy, (Such as YouTube declaring it has ‘’banned all anti-vaccine misinformation(Davey)) it is vital to develop a suitable methodology, define the purposes of the research and the aspects of the algorithm that are being researched clearly, and analyze the phenomena through the lens of the generated data without forgetting the features of the medium that produces the phenomena. In terms of methodology, focusing on a specificity related to the genre of the information provided by the platform would help a researcher by solidifying the digital traces the researcher is looking for. One such study claims that ‘’YouTube intentionally scaffolds videos consistent with the company’s commercial goals and directly punishes noncommercially viable genres of content through relegation and Obscuration’’ (Bishop 71). The method used by Bishop is ‘’reverse engineering’’ where the focus is on three types of data included in the experience of the YouTube users (73).

Venturini’s checklist can be used in order to solidify the claims of this type of research in my opinion. The operationalisation process introduced in the article allows the researcher to relate the digital traces a study finds to the research question, as Venturini states ‘’the key to securing the adequacy between observed phenomenon and repurposed medium is to handle with care the relation between the scope of your research questions and the traces that you will use to investigate them’’ (4204). Furthermore, the checklist provides an opportunity to define a clear-cut definition of what the digital traces related to the object of study could be. To illustrate, it would enable the researchers to specify whether they are focusing on the search algorithm or recommender algorithm of YouTube, which is useful considering the deceptive nature of studying more or less ‘’unseen’’ digital objects. A checklist when researching phenomena generated in digital media will provide the researcher with valuable, self-reflective questions, although it should be noted that such a checklist would also need to be aligned with the scope and purpose of the study.

Conclusion

Studies in new media focus on phenomena that call for adaptability, modifiability, and awareness in terms of methodology. It is therefore vital to develop research methodologies that address the fast-paced and massive structure of the digital culture. The approach presented by Venturini provides a list of questions whose answers would allow scholars to define and demarcate their findings in the field of new media studies.

References

- Bishop, Sophie. ‘’Anxiety, Panic and Self-optimization: Inequalities and the YouTube Algorithm.’’ Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, vol. 24, no. 1, 2018, pp. 69-84. DOI: 10.1177/1354856517736978

- Gillespie, Tarleton. ‘’The Relevance of Algorithms.’’ Media Technologies, edited by Tarleton Gillespie, Pablo Boczkowski, and Kirsten Foot. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014

- Venturini, ‘’Tomasso et al. A reality check(list) for digital methods.’’ New Media & Society, vol. 20, no. 11, 2018, pp. 4195-4217. DOI: 10.1177/1461444818769236

- Alba, Davey. ‘’YouTube bans all anti-vaccine misinformation.’’ New York Times, 29 September 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/29/technology/youtube-anti-vaxx-ban.html

- Southern, Matt. ‘’How YouTube Recommends Videos.’’ Search Engine Journal, 17 September 2021, https://www.searchenginejournal.com/how-youtube-recommends-videos/420288/#close