Stories as Specters of our Past: Evaluating the Impact of Ephemeral Media on Research Practices.

Snapchat’s iconic ghost Chillah is the perfect mascot to represent what helped make the company such an important contributor to the fast-paced, short snaps of content that appear across screens globally today. Snapchat helped lead the way for other apps in mastering the art of ephemeral media – full-screen, short clips – with an added level of transient privacy included.

Chillah, the ghost mascot, is likely attributed in part to their previous app name Picaboo, however using a ghost icon also ties in nicely to the app’s unique technical distinctions – disappearing, self-destructive photos, and videos – only viewable for limited periods. Not only was this a fast, short format to consume media – but it was also easy to use privately.

Very quickly, the appeal of Snapchat’s disruptive and disposable form of social media started to catch onto other platforms. Soon, many other prominent social networks followed suit introducing transient ‘story’ content – including Google, WhatsApp, YouTube, Facebook, Linkedin, Twitter Fleets, TikTok, etc. The appeal of large companies and apps adopting this reflects the significant increase in the user’s preferring shorter ‘bite-size’, 5-7 second, full-screen content. The drawback to this easily accessible format, however, is the inability to look back or search through past content. Not only do they expire – but the user-experience is suited towards new, popular, and promoted content. As Van Dijk (2010) illustrates when looking at Google Search’s commercial biases:

“In a network society, search engines like Google Scholar constitute a nodal point of power, while the mechanism of knowledge production is effectively hidden in the coded mechanisms of the engine… [This becomes] significant when we look at how other public values of information search, such as relevance and privacy, are incorporated in this new powerful network of knowledge production.”

(2010: 579)

Much like Google’s black boxes of algorithms and protocols – Instagram Stories adopt similar practices, by acting as prominent information switchers (Castells, 2009: 46), in that they “handle many specific interface systems that relate and connect a variety of user contexts, which are all crucial to the formation of knowledge.” (Van Dijk, 2010: 583)

What makes platforms like Instagram Stories important to address is not only our general inability to look at past media artifacts – but also the impact in terms of scholastic research throughout a variety of disciplines – as these social networking tools – in a similar way to Google, maintain control over a large cloud of user data. Facebook’s access to both meta-data, as well as visual content – is akin to owning a “mind-map of the collective unconscious’ (Van Dijk, 2011).

It is important to also acknowledge these novel platform practices are an unmapped legal and moral territory where issues are somewhat “unregulated in the virtual bonanza of the Internet” (Van Dijk, 2011). This untapped and unregulated space of media consumption is also why it is vital to consider the relevance of these spaces for researching commercial, political, or otherwise malicious use of story content while they are key switchers of knowledge production and social capital.

Paradoxically, while most of the story content or user data is often hidden, inaccessible, or lost over time from the public sphere or research-data compiling technologies – it is simultaneously better recorded and archived (by private businesses) than previous analog media forms, due to its digital nature. As Grainge (2011) explains:

“All digital inscriptions leave a nanotechnological trace and can therefore never be lost entirely, the web is distinguished by its fast, fleeting, and upgradable nature. As a media environment, the web is ephemeral in its volume and variety of content, but also in its temporal structures of viewing and interaction”

(Grainge 2011: 9)

Given the success of story content, it is no surprise too that this includes a large adoption by online marketing companies – who both want to feature their marketing content within the fast-moving and fleeting cloud of User’s story content – but also want to tap into the ‘virtual bonanza’ by learning user behavior and targeting them through the available data. Story platforms in this way are both in control over which content is played to us when or where – as well as acting as prominent profilers – compiling our behaviors into grouped categories for unique media suggestions. Like the power of search engines, this involves a collective profiling of users and “may eventually shape the production of knowledge,” and an “unfair competitive edge over (public) researchers when it comes to the availability and accessibility.” (Van Dijk, 2011: 585)

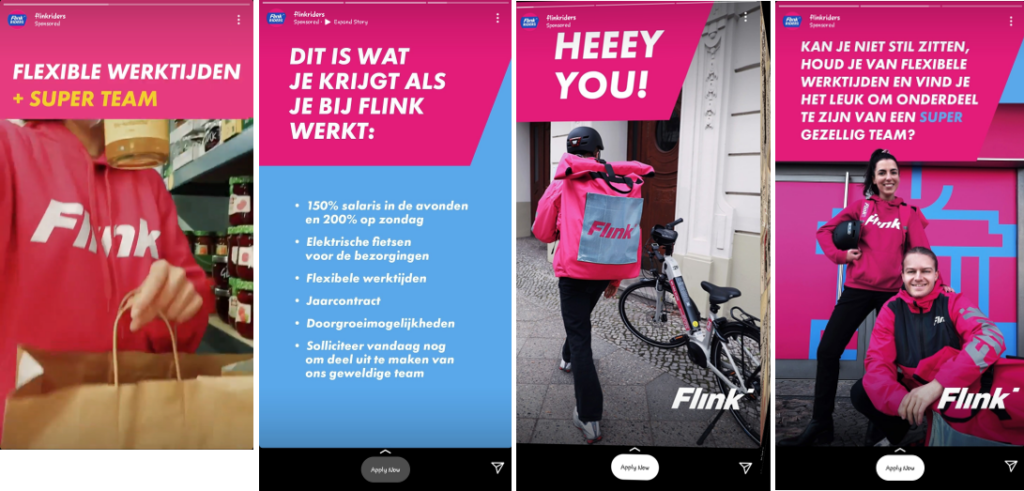

The commercial successes gained from user data combined with promoted content helps reinforce the privatization of data and a lack of transparency of knowledge production. On Instagram, there exist over 8 million business accounts, and over 1 million clients paying to have their advertisements rank higher-up in the algorithm’s flow of content. A large part of this appeal beyond reach and engagement for marketers – is the numerous levels of online behavioral targeting (OBT) plays in allowing you to profile and switch content tailored for specific audiences. This is usually done with a combination of audience segmentation as well as split testing of promoted advertising content – all of which Facebook makes easily accessible via their gatekeeping business enterprises.

This is amplified when considering the role of anthropomorphism that is being leveraged for commercial interests. Anthropomorphism refers to the way in which we attribute human characteristics towards machine actors – and in this regard, onto the algorithms designed to curate your social media feeds as well as promoted content. Studies have shown that anthropomorphized technology creates a higher level of social presence, engagement, purchasing intent, and brand trust (e.g., Choi et al., 2011; Verhagen et al., 2014, Skalski & Tamborini, 2007, Lui & Wei 2021).

In a recent study, Lui & Wei (2021) show how “we treat computers like persons only when we do not have sufficient knowledge about their algorithms.” Their results find that the highest level of social presence and social influence happens when users do not have access to how their data is being analysed – or are made unaware of any actor ranking, selecting, and personalizing content for them (Lui & Wei, 2021). Because we, by default, “respond to the machine gaze similarly to how they respond to the human gaze” we are also by default more inclined to engage, interact, and ultimately purchase thanks to a heightened level of anthropomorphism. (2021)

In this sense, it is in the benefit of commercial enterprises to maintain hegemonic control over the black-box algorithms that profile and curate our story content – with the inner workings swept up in the transient nature of these media platforms. One final complication that deepens this transience is the increasing use of split A/B testing and ‘smart selections’ for content creators and online marketers. The consumption space and process are now entirely personalized and private. Instead of the one-to-one model – it has become a one A/one B-to-exactly-this-one model. Facebook, Google, and similar platforms afford advertisers with the function of uploading multiple iterations of a piece of media to test and adapt it based on real-time performance diagnostics. Because of this – we are at any time seeing only one version of many possible iterations – sometimes uniquely created – or other times algorithmically generated from separate elements like font, copy, images, and layouts, etc.

While there are many challenges in terms of accessing and researching ephemeral data sources like Instagram Stories or Snapchats– there are still many different insights we can distill – even without having access to the full map. Rogers (2021) outlines many ways that smaller samples of data can carry relevant visual insights when looked at in different ways. Likewise, we need to find creative ways to research, analyze and open up the black boxes of ephemeral media that fly in and out of our screens and lives – like tiny ghosts – disappearing as fast as they seem to manifest.

Bibliography

Castells, Manuel (2009) Communication Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Charteris, Jennifer, Sue Gregory, and Yvonne Masters. 2018. “‘Snapchat’, Youth Subjectivities and Sexuality: Disappearing Media and the Discourse of Youth Innocence.” Gender and Education 30 (2): 205–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2016.1188198.

Choi, Jaewon, Hong Joo Lee, and Yong Cheol Kim. 2011. “The Influence of Social Presence on Customer Intention to Reuse Online Recommender Systems: The Roles of Personalization and Product Type.” International Journal of Electronic Commerce 16 (1): 129–54.

https://doi.org/10.2753/JEC1086-4415160105.

Grainge, Paul, ed. 2011. Ephemeral Media: Transitory Screen Culture from Television to YouTube. Houndsmill, Basingstoke, Hampshire ; New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Liu, Bingjie, and Lewen Wei. 2021. “Machine Gaze in Online Behavioral Targeting: The Effects of Algorithmic Human Likeness on Social Presence and Social Influence.” Computers in Human Behavior 124 (November): 106926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106926.

Rogers, Richard. 2021. “Visual Media Analysis for Instagram and Other Online Platforms.” Big Data & Society 8 (1): 205395172110223. https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517211022370.

Skalski, Paul, and Ron Tamborini. 2007. “The Role of Social Presence in Interactive Agent-Based Persuasion.” Media Psychology 10 (3): 385–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213260701533102.

Verhagen, Tibert, Jaap van Nes, Frans Feldberg, and Willemijn van Dolen. 2014. “Virtual Customer Service Agents: Using Social Presence and Personalization to Shape Online Service Encounters.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 19 (3): 529–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12066.