How the Wall Street Journal made Facebook Inc. release an internal research

In the middle of September of 2021, the Wall Street Journal added an article to their ‘Facebook files’. This article surrounded Facebook’s internal research on Instagram and the negative effects it might be able to have on its users, especially on teen girls. Facebook’s research indeed confirmed that Instagram contributes to the negative self-image of teen girls (Wells, Horwitz & Seetharaman, 2021). In the end, the findings were not the issue for The Wall Street Journal, it was action – or rather the lack of action – Facebook took after the research was done. The article raised a lot of questions, reaching as far as the US Senate, who later on scheduled a hearing for Facebook Inc. talking about the harmful effects of a teen’s mental health (Seetharaman, 2021). In 2012, a research article was published by boyd and Crawford about Big Data. They describe Big Data as “a cultural, technological, and scholarly phenomenon…” It is a network consisting out of three parts: technology, analysis, and mythology. This essay is mostly focused on the analysis, where data sets are used to find connections to create claims regarding the economic, social, technical, and legal topics. Their research asked six critical claims about some of the issues within Big Data. Three of the claims in the text are relevant for this essay: “Claims of objectivity and accuracy are misleading”; “Taken out of context, Big Data loses its meaning”; and “Limited access to Big Data created new digital divides”. On the basis of these claims, I am going to look at Facebook’s research and the publications from the Wall Street Journal and base these claims on what happens after Big Data is already applied to the research, trying to see if these claims not only withstand during the research process but also when the Big Data research is already released.

Facebook’s research

Facebook’s research, which was internally released in 2019, consisted out of focus groups, online diary studies, and in-depth interviews and additionally “it also includes large-scale surveys […] that paired user responses with Facebook’s own data about how much time users spent on Instagram and what they saw there.” (Wells et al., 2021) The conclusions were stated and possible solutions to the issues were made by the researchers. Facebook’s internal research on Instagram’s negative impact on body image and mental health issues on young girls and women are not groundbreaking findings. An example of this is the 2017 research done by Cohen, Newton-John and Slater called The relationship between Facebook and Instagram appearance-focused activities and body images concerns in young women who concluded that “appearance-focused content on Instagram, relate to various body image concerns, whereas overall SNS consumption may not.” Even back in 2017, it was known to the public that the mental health of teenage girls was greatly affected by Instagram.

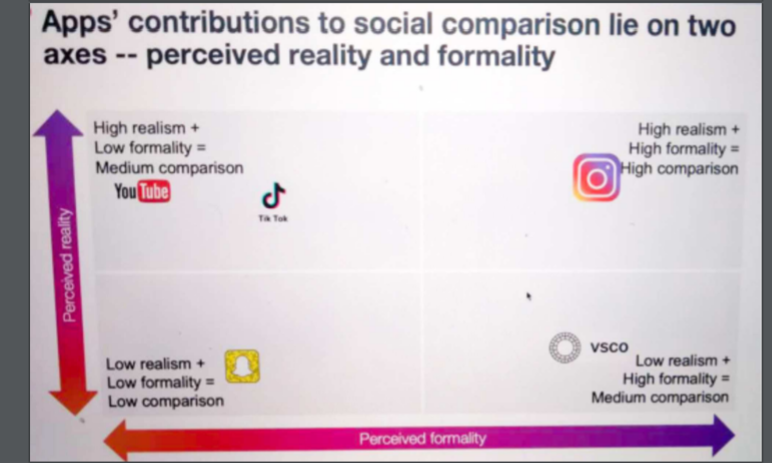

Following Facebook’s research Instagram contains a high perceived reality alongside a high perceived formality, meaning that even though the pictures on the app are edited, one still sees them as reality. This explains why teenage girls have a higher tendency to social comparison when a photo is manipulated than when a photo is not manipulated (Kleemans, Daalmans, Carbaat & Anschütz, 2016).

The aftermath

The Wall Street Journal did not only take issue with the research itself as mentioned before; Facebook had downplayed the negative effects of the app (Wells, Horwitz & Seetharaman, 2021). One of the issues within Big Data is the “claims to objectivity and accuracy are misleading”. Crawford and boyd discuss the interpretation of Big Data during the research process. Naturally, after the research is published the results are open for interpretation as well. The interpretation process continues from the researchers trying to make the patterns and the claims to the Facebook executives who get the end result. As Crawford and boyd quote Gitelman (2011): “every discipline and disciplinary institution has its own norms and standards for the imagination of data”. Following Instagram’s head Adam Mosseri the effects of Instagram on teens’ mental and physical health are not that big (Wells et al., 2021). Continuing that he does not want to diminish the results of the research, saying that some of the issues can impact one greatly, nonetheless, it is not a universal concern. This part clearly shows that Mosseri had other interpretations of the research than what the Wall Street Journal addressed. He admitted that some of the features are harmful, continuing to balance it out with the quote “There’s a lot of good that comes with what we do.” Along with the researchers’ biases and subjectivity during the research process, they likewise need to take them into account for the readers after the research is published.

Facebook’s response

Eventually, Facebook Inc. itself released the two pieces of research that were the main focus of the Wall Street Journal’s articles. They criticized the Journal, claiming that on eleven of the twelve areas – such as anxiety and eating disorders – Instagram made the teenage girls feel better while struggling with these issues (Raychoudhury, 2021). Raychoudhury, head of research, clarified in the article where the researches are enclosed, that only the worst results were displayed on the slides in order for them to focus on the things they can improve. It also touches upon the claim “Taken out of context, Big Data loses its meaning”. Raychoudhury wrote that the researchers added annotations to provide more context for their findings and called the Wall Street Journal’s interpretations of Facebook’s research mischaracterizations. The Journal came with their own claims after they were not provided with the extra context. The possibility could be that the Journal drew other conclusions if they were provided with these annotations.

“In public, Facebook has consistently played down the app’s negative effects on teens and hasn’t made its research public or available to academics or lawmakers who have asked for it.” (Wells et al., 2021) This quote brings us to the sixth provocation: “Limited access to Big Data creates new digital divides”. Crawford and boyd discuss that large data companies can choose not to publicize their data. Therefore, Facebook can control who and who does not have access to their database; and who eventually is able to read the results.

Conclusion

In conclusion, boyd and Crawford’s claims on Big Data can be used in the context of the research results after the research is published. These claims point out the tension between Facebook Inc. and the Wall Street Journal surrounding the results of Facebook’s internal research. Several types of research can be dedicated to these topics, but I wanted to focus on the surface-level interaction between the two sites.

References

boyd, danah & Crawford, Kate. ‘Critical Questions for Big Data’. Information, Communication & Society 15, no. 5 (1 June 2012): 662–79.

https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.678878.

Cohen, Rachel; Toby Newton-John & Amy Slater. ‘The relationship between Facebook and Instagram appearance-focused activities and body image concerns in young women’. Body image 23 (19 October 2017): 183–87.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.10.002.

Facebook researchers (2020) ‘Teen Girls Body Image and Social Comparison on Instagram – An Exploratory Study in the U.S.’

Kleemans, Mariska; Daalmans, Serena; Carbaat, Ilana & Anschütz, Doeschka. ‘Picture Perfect: The Direct Effect of Manipulated Instagram Photos on Body Image in Adolescent Girls’. Media Psychology 21, nr. 1 (2 Januari 2018): 93–110.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2016.1257392.

Raychoudhury, Pratiti. About Facebook. ‘What Our Research Really Says About Teen Well-Being and Instagram’, 26 September 2021.

Seetharaman, Deepa. ‘Senators Seek Answers From Facebook After WSJ Report on Instagram’s Impact on Young Users’. Wall Street Journal. (15 September 2021): sec. Tech.

‘The Facebook Files’. Wall Street Journal, 1 October 2021, sec. Tech.

https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-facebook-files-11631713039.

Wells, Georgia; Horwitz, Jeff & Seetharaman, Deepa. ‘Facebook Knows Instagram Is Toxic for Teen Girls, Company Documents Show’. Wall Street Journal. (14 September 2021): sec. Tech.