My Fitness Pal; the power of search engines and world building

Jasmin

Figure 1

In 2021, the Fitness market (estimated by The Wellbeing Creative Co.) was valued at $96.7 bn. This calls into question for us as media scholars; how does the fitness market manifest and present itself within the context of digital media? Furthermore, what can we as scholars contribute to understanding this digital phenomenon; both the virtues and the vices that come along with it.

One example of the fitness world manifesting on digital platforms is the My Fitness Pal app which was sold by Under Armour for $345 million in 2020, according to Tech Crunch. My Fitness Pal is a free app for tracking calories, exercise, and habits in order to lose, maintain or gain weight. Recommended by the New York Times in 2021 for it’s ability to act as a personal coach. One of the main advertised functions is in its ability to track calories. Citing on its website as having a database of over 11 million foods with the portions and calories pre-calculated.

Figure 2 Home page of myfitnesspal.com

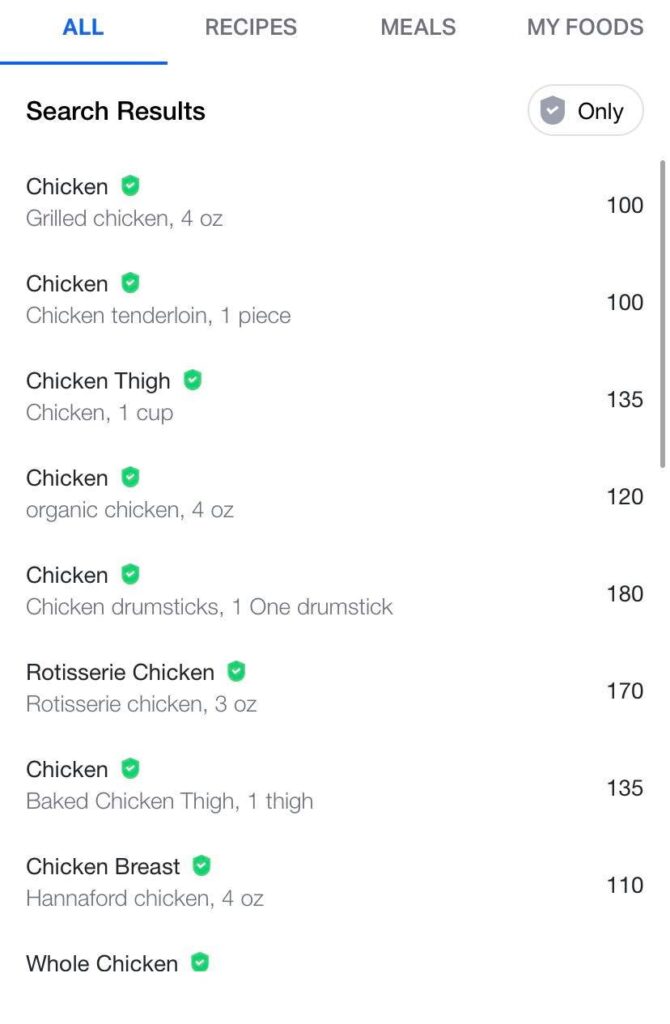

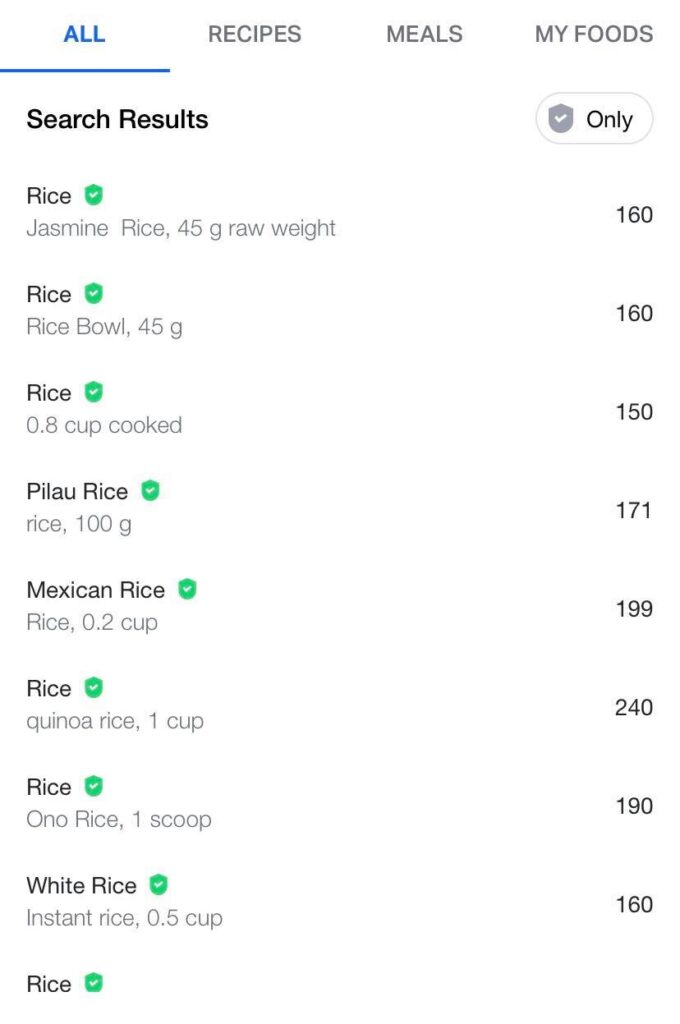

In order to log your meal, you search for each individual ingredient, and they offer you which food type to log alongside a pre-calculated calorie count (figures 3 and 4). This is reminiscent of José Van Dijck’s research regarding search engines and the production of knowledge. In this paper she argues that search engines have the power to sort and value search results, and in turn academic papers. This gives search engines the power to shape how the user digests and understands information within the context of that database, making these search engines ‘nodal points in networks of distributed power’(579). Ultimately arguing that these search engines have the power to shape which papers are easily accessible according to their own algorithmic logic. Van Djick (557) argues that as this search engine algorithm ranks papers according to their popularity, number of citations and number of clicks. This in turn, according to Van Djick, makes the search engine the mediator between the knowledge and the researcher. Allowing the search engine to control visibility and relevance with regards to academic publications. Giving therefore, the search engine both an invisible and influential powerful position. Van Djick then goes on to say that as a result of this power, the search engine creates an eco-system of knowledge and knowledge production, effectively world building.

Figure 3 + 4 Search results within My Fitness Pal

The questions here relating to My Fitness Pal are two-fold then, what amount of power does presenting food understood in terms of calorie count imply, and how does this kind of search engine therefore, begin to create a digital world understood through the app?

My Fitness Pal is marketed as a companion to a healthy lifestyle, however, the only diet tracking option is to see meals as individual ingredients, and then ultimately, numbers of calories. This infrastructure pushes the user into understanding their meals not in terms of their holistic value as numbers on a plate, of which one can only eat so many. This practice is aligned with diet culture and can be harmful, as opposed to intuitive eating, where food is not approached as a calorie -count or labelled good or bad (Carbonneau et al. 207). This approach has been reported by Van Dyke (8) as being effective in adults, teens and children to decrease practices of disordered eating and increase a healthier diet. Additionally, here is a wealth of research tying the use of calorie counting apps with eating disorders with Hahn et. al (2) reporting that;

“in a sample of females seeking treatment for an eating disorder, 75% reported using MyFitnessPal to count calories and 73% of those who used MyFitnessPal to count calories believed the app contributed to the development of their eating disorder.”

However, as Hahn et. Al (10) then research a randomised sample of college students with low risk of developing an eating disorder, they found no great increase in the risk of development of signs of disordered eating after a month of online calorie tracking. The operational condition being a low risk of developing an eating disorder. This study concludes that calorie tracking apps may not increase the chances of developing an eating disorder if calorie tracking is not already a ‘pre-existing harmful behaviour’. This does however offer an interesting insight into the development of eating disorders and how online behaviour can affect and amplify pre-existing behaviours.

This then brings to mind; how can online search engines affect the consumption of knowledge in areas other than academia and google search results? In the case of My Fitness Pal, presenting food options to only be understood within the context of calories brings into question how applications can build a world fashioned in the image of the designer’s vision. Giles and Guattari (21) would argue that self-making should be seen as a process that is affected by outward forces, shaping desire and the aspirational being. Ultimately arguing that the social will always affect desire, and desire shapes the way people choose to live their lives. Therefore, begging the question, can the mediated approach to understanding food be shaped by these processes? It seems, that according to Van Dijck’s theoretical work regarding the knowledge building power of the search engine, and recent research on fitness apps and calorie counting, that indeed, it seems as though they may influence each other.

This blog post has explored one aspect of how the digitisation of fitness apps can affect one’s attitude towards food, as well as considering how José Van Dijck’s criticism of the search engine as an invisible power structure can be applied in to further enhance knowledge regarding this media object. The question remains, how should we as media scholars, and as stewards respond?

Works Cited

“Fitness Market Size, Revenue & Growth 2021 [+ Research Report]”. Wellness Creative Co, 2021, https://www.wellnesscreatives.com/fitness-market/.#

“Photo By Dan Gold On Unsplash”. Unsplash.Com, 2021, https://unsplash.com/photos/4_jhDO54BYg?utm_source=unsplash&utm_medium=referral&utm_content=creditShareLink.

Carbonneau, Noémie et al. “From Dieting To Delight: Parenting Strategies To Promote Children’S Positive Body Image And Healthy Relationship With Food.”. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, vol 62, no. 2, 2021, pp. 204-212. American Psychological Association (APA), https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000274.

Etherington, Darrell. “Techcrunch Is Now A Part Of Verizon Media”. Techcrunch.Com, 2020, https://techcrunch.com/2020/10/30/under-armour-to-sell-myfitnesspal-for-345-million-after-acquiring-it-in-2015-for-475-million/?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmllLw&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAIzivC0XOzR6XcnOr0mgWRYXEOglp_a-F6060J_uIongPR_wQEzteQTlVkzW5615sj3_DuKxl_8RqRykucOo2G1RHd-klEfPQBV5Rgjcd8GETjOS-Djih1k7_mg2_CwncaGJuSQrljUKemM5PER2Pv8-3garEnLsE012PQFhuIeE.

Hahn, Samantha L. et al. “Introducing Dietary Self-Monitoring To Undergraduate Women Via A Calorie Counting App Has No Effect On Mental Health Or Health Behaviors: Results From A Randomized Controlled Trial”. Journal Of The Academy Of Nutrition And Dietetics, 2021. Elsevier BV, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2021.06.311.

Hipfl, Brigitte, and Elena Pilipets. “Digital Youth Assemblages: Affective Entanglements Of Sharing (Anti-)Selfies On Instagram”. Medienjournal, vol 44, no. 2, 2020, pp. 19-32. Facultas Verlags- Und Buchhandels AG, https://doi.org/10.24989/medienjournal.v44i2.1948.

van Dijck, José. “Search Engines And The Production Of Academic Knowledge”. International Journal Of Cultural Studies, vol 13, no. 6, 2010, pp. 574-592. SAGE Publications, https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877910376582.

Van Dyke, Nina, and Eric J Drinkwater. “Review Article Relationships Between Intuitive Eating And Health Indicators: Literature Review”. Public Health Nutrition, vol 17, no. 8, 2013, pp. 1757-1766. Cambridge University Press (CUP), https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980013002139.