Presearch: challenging the current framework of proprietary search engines and production of knowledge.

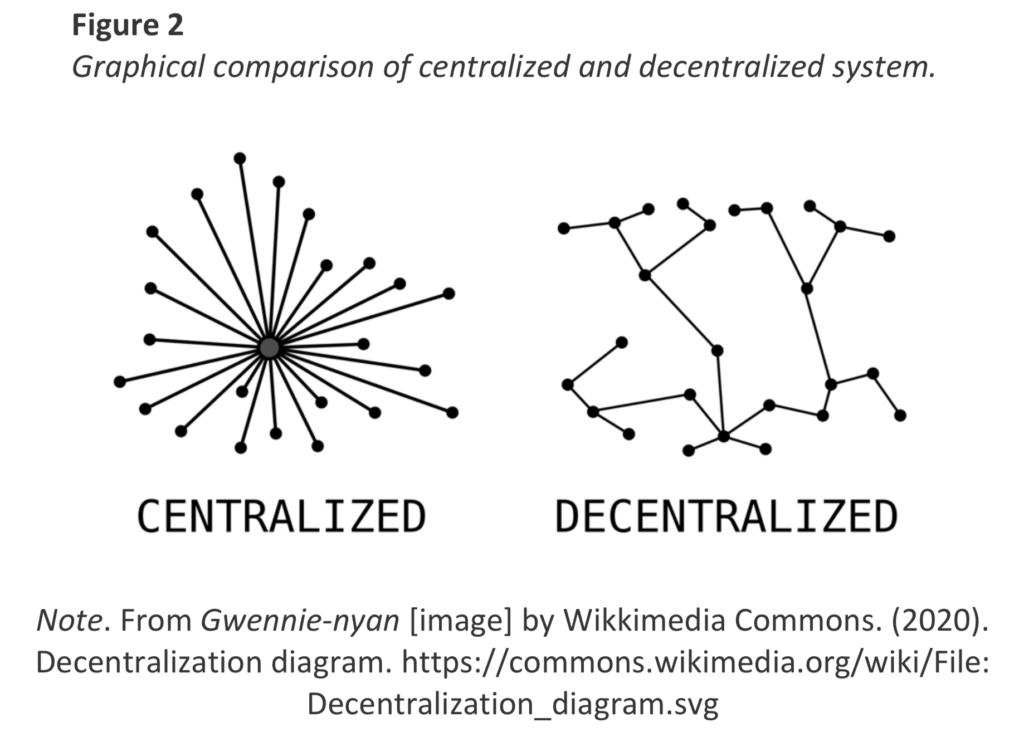

As the current proprietorship search engine providers are not open and fully transparent and their technologies are influenced by economic, political and social factors, the framework for information literacy becomes more and more complex. Distributed search engines aim to replace conventional search engines by redistributing power and control of information networks.

The debate on conventional search engines and Van Dijck’s call to information literacy

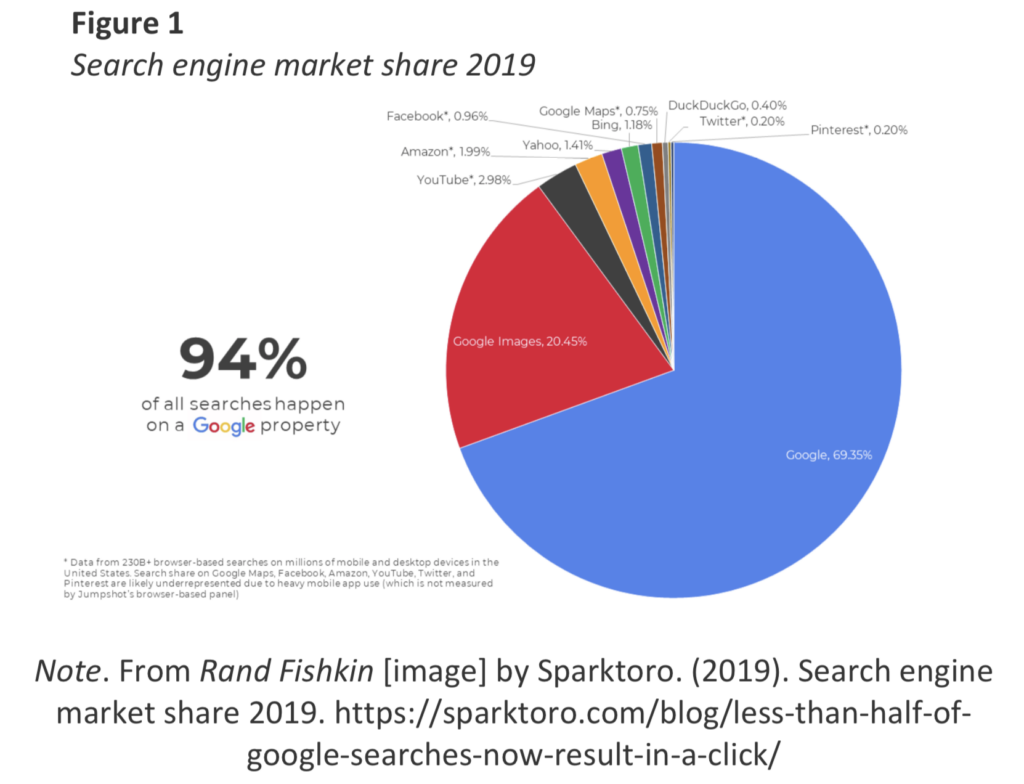

In the last two decades, search engines have become fundamental and irreplaceable tools in the creation of knowledge. Critiques and discussions around the debate of search engines, especially that of Google, have been at the heart of information media studies due to the influence they exert to information access and knowledge production.

Van Dijck in “Search engines and the production of academic knowledge” has elaborated further on this topic, focusing on the implications proprietary search engines have in construction of scholarly knowledge. In the author’s critique to proprietorship search engines, Van Dijck underlines the importance of information literacy in the process of knowledge production, which is defined as a set of technical skills but also including the social, political and economic forces of proprietary search engines that affect construction of knowledge.

Although Van Dijck’s article focuses mainly on the knowledge production within the scholarly context her critique to proprietary search engines raises points that appear to be relevant at all levels of production of knowledge. The author affirms: “If Google has become the central nervous system in the production of knowledge, we need to know as much as possible about its wiring.”

But the question raises spontaneous: how effective can information literacy be in the current centralized framework? how much could we ever know about these black boxes?

In contrary to Van Dijck’s vision of Web 3.0 as the Semantic Web where knowledge is redefined by algorithms infinitely more complex calling to the importance of information literacy, the rise of peer-to-peer distributed search engines as technologies of Web 3.0 are reshaping the distribution of power among the users accessing and delivery of information in much more transparent, democratic and unbiased ways.

In light of the Van Dijck’s critique this article will analyse the vision of Presearch (a blockchain-based decentralized search engine) that seems to be challenging Google search and other proprietary search engines more than any other technology, by developing a modern distributed architecture, reshaping the current paradigm that currently defines knowledge production.

Presearch – A vision that challenges and reshapes the frameworks of proprietary search engines

Presearch is a distributed search engine that utilizes peer-to-peer and blockchain technology that aims to create a community driven search engine framework.

Although Presearch’s engine interface appears just as straightforward as that of Google, providing users with an interface with a simple search bar, in contrary to how Van Dijck has described Google’s interface, this simplicity seems to resonate with values of transparency and openness rather than “complex and invisible underlying algorithms” (Van Dijck, 2010). As decentralized search engines’ challenge in reconfiguring centralized digital environments heavily rely on users’ participation to the network and people ‘accept greater control in return for greater convenience’ (Nicholas Carr, 2010), Presearch’s vision and growing community are challenging this statement. Presearch presents itself as a community-powered, distributed search engine “that provides better results while protecting your privacy … [it] offers its users increased search choice and active personalization, where they are in control of their experience, rather than automated personalization built upon a foundation of tracking and profiling users.”

Even though Presearch is still of its way of becoming a fully distributed platform, it has already achieved significant steps in terms of decentralization. As it is stated on Presearch’s whitepaper published in 2017, their vision of a community-powered search engine consists on “enabling users to participate in the creation and success of the platform … for instance, teams of data scientists could contribute algorithms, subject matter experts could curate collections of content, UI designers could create novel interfaces, and those running nodes could crawl and index the web. All would be rewarded with tokens based on the value of their contributions.”

When using conventional search engines, users don’t only lose ownership of information but they also allow others to profit from that data. Presearch alters this model putting the users in control of their data and making them benefit from their activity within the network; whether sensitive data is revealed or kept private, searches create tokens for the querying users. As in distributed networks the absence of a central authority implies an active participation of users in sustaining the network, constituents are incentivized to do so through economic rewards either by acting as nodes in the network or through their search activity.

Presearch’s model a decentralization of power also implies an economic redistribution (allowed by blockchain technology and digital ledgers), positioning itself in complete contrast with the idea of communicative capitalism (Dean, 2016) that governs the current digital landscape of the conception of search engines as a service.

Decentralized search engines and Web 3.0: reducing the barriers to information literacy

The idea of proprietary search engine has been strongly criticized in an era where information networks are owned by private companies that operate not necessarily in benefit of the user and adhere to specific values governed by political, social and economic interests (Van Dijck, 2010). In the vision of an internet where information systems and their data streams and algorithms become more and more connected and complex, the discussion of the importance of information literacy in information search has become more and more relevant in the digital era.

Van Dijck in this vision of Web 3.0 as the Semantic Web affirms with a slightly negative connotation that production of knowledge is becoming increasingly automated: “intelligent systems based on tracking, interpreting and predicting intuitive behaviour of human actors”. The Semantic web, as envisioned by Berners Lee has lost stream and turned out to be not as popular as the decentralization perspective of Web 3.0 that we are living in. In a way, we are going back to the original concept of web as theorized by Berners Lee, where there is no central controlling node, no points of failure, where no central authority needs to grant permission to act within the network and no ‘kill switch’ that could shut it down.

In fact, the rise of decentralized systems is based on a vision opposed to this idea of automated knowledge production, where users are profiled and constantly tracked. Decentralized web is creating transparent, neutral, and democratic environments in full control of the user.

With decentralized search engines the external forces that determine and influence the construction of knowledge in what Van Dijck defines as the “dynamics of network connections and their intersections” do not represent anymore that of single private entities but are community driven. In this way knowledge production is not anymore coproduced by proprietary search engines but is produced both by users and the community itself.

As with the vision of Presearch of a distributed search engine the framework of information literacy is freed from political, social and economic forces of single private entities, the tools for information literacy slowly start to become much more accessible, destroying the barriers that untransparent practices of proprietorship search engines have raised.

Bibliography:

Anderson, M. (2019, February 7). Exploring Decentralization: Blockchain Technology and Complex Coordination. Journal of Design and Science. https://jods.mitpress.mit.edu/pub/7vxemtm3/release/2.

Carr, G. N. (2010). The Shallows”: This Is Your Brain Online. W.W. Norton.

Dean, J. (2016). Faces as Commons: The Secondary Visuality of Communicative Capitalism. Open! Platform for Art, Culture, and the Public Domain.

Presearch.org Global Limited. (n.d.). Presearch – A Better Search Engine For We The People. Presearch.org Global Limited. Retrieved Semptember 28, 2021, from https://www.presearch.io/about.

Presearch.org Global Limited. (2017). Presearch Whitepaper [White paper]. Presearch.org Global Limited. https://whitepaper.io/coin/presearch.

Presearch. (2017, July 8). Presearch Demo [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BfslE5GPKYM.

Rayan, J. P. (2019, September 30). Why decentralize. Medium. https://medium.com/decentralized-web/why-decentralize-5d8e9dcedb2c.

Rilley, G. (2012, September 6). Man who invented web: “No, there is no button to kill the internet.” The Journal.ie. https://www.thejournal.ie/tim-berners-lee-no-kill-switch-586056-Sep2012/.

Van Dijck, J. (2010). Search Engines and the Production of Academic Knowledge. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 35 (6), 574–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877910376582.