Like, swipe, match… “you vaxxed?”

How Hinge and Tinder have adapted their affordances to the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic caused a spike in dating app usage while simultaneously altering the standard dating practices. To analyze how dating apps have responded to this change, we used an affordance analysis walkthrough method, as well as secondary sources, to look at the popular dating apps Hinge and Tinder. We found that these apps adapted their features to accommodate dating in a pandemic. These changes fit three overarching themes: facilitating the sharing of pandemic experiences, easing the online dating experience, and promoting healthy pandemic habits. Ultimately, the two apps demonstrate a clear stance on public health, which they promote to their users.

By Aaron de Rijke, Sheng Wong, Simran Tamber, and Tom Weber

Introduction

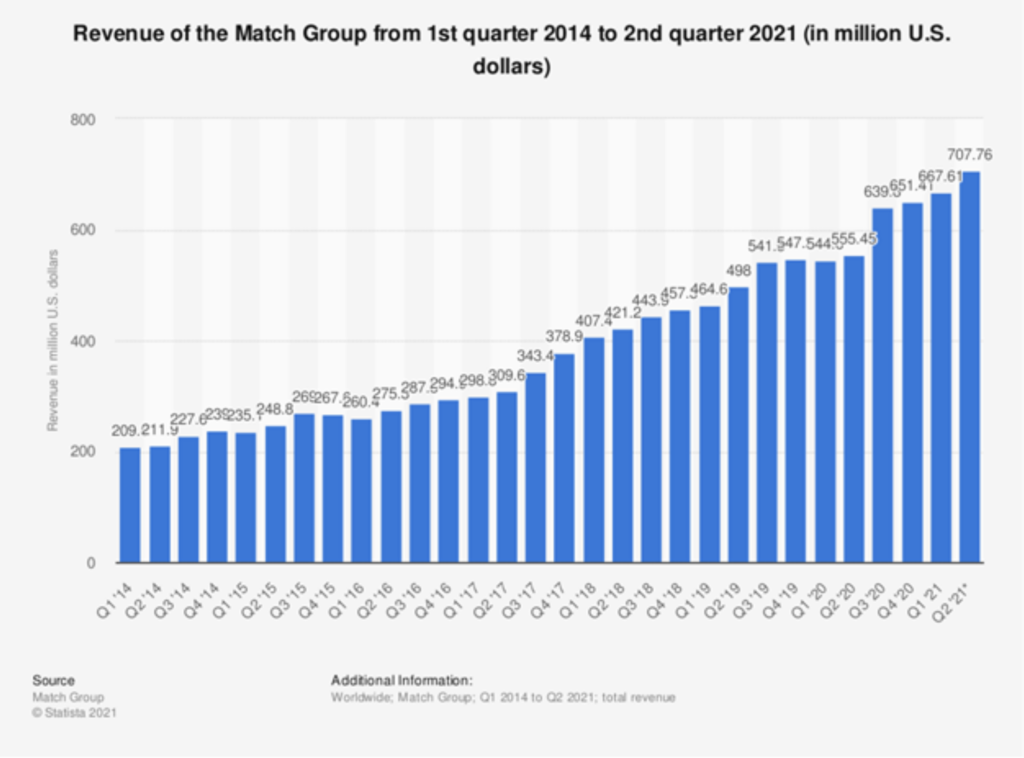

2020 was the busiest year for Tinder, the most popular dating app, with a 42% increase in matches (‘The Future of Dating Is Fluid’). The record for most swipes on one day, three billion, was broken on March 29th, around the start of worldwide lockdowns due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Dating app Hinge, which presents itself as more relationship-oriented than Tinder, saw downloads increase by 63% and ad revenue triple during the pandemic (Saner 2021). Both apps are a part of Match Group, which saw a significant increase in revenue in the latter half of 2020 (see figure 1).

However, the traditional cycle of dating app usage (connecting, chatting and meeting up in real life) wasn’t possible due to worldwide lockdowns. To keep the increasing number of members engaged in this changing dating landscape, dating apps have understandably adapted their strategies and features. This blog will attempt to map some of these key changes on Tinder and Hinge by answering the following research question: How have the affordances of Hinge and Tinder adapted to the COVID-19 pandemic? Further, we strive to analyze how these changes affect contemporary dating by exploring how these modifications shape contemporary online dating. We aim to answer these questions via an affordance analysis of Tinder and Hinge, supplemented by primary and secondary sources.

Theoretical Context

The notion that online platforms, mobile or not, are not neutral, naturally evolving “media ecologies,” but are instead developed to further a range of personal, corporate, or financial interests, has been at the center of scholarly attention in the field of new media studies for a number of years already (Venturini et al.; Davis and Chouinard; Poell et al.; McVeigh-Schultz and Baym). Scholars acknowledge the multitude of ways in which platforms exert power over users by means visible and invisible to them, and, in return, how users renegotiate those multi-layered power relationships through interactions on said platforms and in interaction with their features and other technological affordances.

Poell et al. coin the term “platformization” to highlight the “penetration of the infrastructures, economic processes, and governmental frameworks of platforms in different economic sectors and spheres of life” (Poell et al. 5). Here, a focal point of their definition of platforms is the systematic collection, processing, and monetization of data that organize interactions in digital infrastructures. The authors argue that this dynamic results in an inherently imbalanced power relation between platform owners and users, as the former have exclusive access to the technological substructures of said platforms and are in control of their techno-economic development (Poell et al. 6).

Davis and Chouinard suggest an understanding of the ways in which technological artifacts shape the experience of their user through the lens of their affordances. They define affordances as “the range of functions and constraints that an object provides for,” distinguishing between real affordances as all potential functions an object offers and perceived affordances as the set of functions visible to the user (Davis and Chouinard 244). McVeigh-Schultz et al. employ the term to “account for the ways that technological artifacts or platforms privilege, open up, or constrain particular actions and social practices” (2). Suggesting the notion of “vernacular affordances,” the authors emphasize the complexity of affordances, in that they are not experienced in isolation as a single piece of material structure or distinct feature of an artifact, but make meaning as part of a complex ecology of other affordances on various levels (McVeigh-Schultz and Baym 10).

Building on the notion of technological affordances, and in accordance with Poell et al., Mel Stanfill argues that they are an expression of the underlying assumptions, ideals, and norms that shape the way in which a user interacts with a platform, and, in turn, contribute to the production of a “normative user” (Stanfill 1065). Through their affordances, technological artifacts offer users varying degrees of freedom and determine their use through request, demand, encouragement, and discouragement.

In the past, other scholars have applied infrastructure studies approaches to understand interrelations and interdependencies between platforms, operators, and users. Star and Bowker highlight that infrastructures are inevitably interlinked with those who create, maintain, and use them. They are deeply embedded into other structures and technologies, are designed to be largely invisible to the user, and only render themselves visible when they break down (Susan Leigh Star and Geoffrey C. Bowker 233).

In their study of Google and Facebook, Plantin et al. combine both infrastructure studies and platform studies. The authors argue that, in essence, both frameworks represent the study of underlying, supporting substructures, but that their differing methodological approaches and historical origins conceal their relationship – “digital technologies have made possible a “platformization” of infrastructure and an “infrastructuralization” of platforms” (Plantin et al. 294).

Similar to Plantin et al., Esther Weltevrede applies a hybrid approach of infrastructure and platform studies to examine inbound and outbound data flows of dating apps. The author characterizes dating apps as “data objects that engage in multiple relationships, bringing together data from heterogeneous origins and simultaneously making those data available to external stakeholders” (Weltevrede and Jansen 1). She proposes the notion of “intimate data” to account for the ways in which the deep embeddedness of mobile devices in daily lives and practices allows for the generation of data that depicts a representation of our everyday habits more accurately than ever before (Weltevrede and Jansen 4).

Methodology

Hinge and Tinder, two of the most popular dating apps, saw their usage drastically increase when the pandemic started, bringing new features and affordances that represented a shift in online dating practices. We will apply an affordance analysis via technical walkthrough, coupled with primary and secondary sources around Hinge and Tinder, to assess features created, adapted, or made accessible as a result of COVID-19.

Affordances

According to Davis and Chouinard, the concept of different affordances illustrates that these individual assets are one cluster of what are considered ‘interrelated mechanisms.’ These ‘artifacts’ have the ability to request, demand, allow, encourage, discourage and refuse, with artifacts defined as what the app provides the individual (Davis and Chouinard 242).

Requests and demands are types of actions that the artifact affords — for example, a request would be a notification asking users to upload a profile picture on Tinder, while a demand would be the app requiring them to input a phone number. Encouragement, discouragement and refusal are other ways the artifact may respond to users, based on their desired actions — for example, swiping for more profiles on Tinder is an encouragement, Tinder discourages careful selection, and a refusal is how Tinder caps the number of swipes in a period of time. Allow refers to when an artifact is “ indifferent to if and/or how a particular feature is used, and to what outcome “ — for example, Hinge allows its members to scroll through a match’s profile (Davis and Chouinard 242).

The walkthrough method

Further, a method to study software applications coined by Light et al. is the “walkthrough method,” which they created as “a way of engaging directly with an app’s interface to examine its technological mechanisms and embedded cultural references to understand how it guides users and shapes their experiences” (Light et al. 2).

The walkthrough method is conducted through a step-by-step observation which entails gathering evidence from app screens, features and flows of activity, and simple interactions (such as screenshots of the interface, audio recordings, and video recordings). This meticulousness ensures that intricate details are mapped out in a way that mimics an app’s stages, everyday use, and even discontinuation of use, but also takes into account ethical considerations and is careful not to include any living subjects in the research (Light et al. 6).

Primary and secondary sources

The analysis will also look at primary and secondary sources of information such as official social media accounts, websites, news articles, and press releases to garner a contextual understanding of how the pandemic circumstances drove changes in how both dating apps adapted. It is important to note that features of dating apps vary from country to country and that the focus of this analysis isn’t limited to one geographical location. Rather, we will highlight examples of how the apps have adapted during the pandemic in varying situations.

Findings

Using the methodology described above, we found that Hinge and Tinder have added, disabled paywalls to, and removed numerous features in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. These features fit three overarching themes:

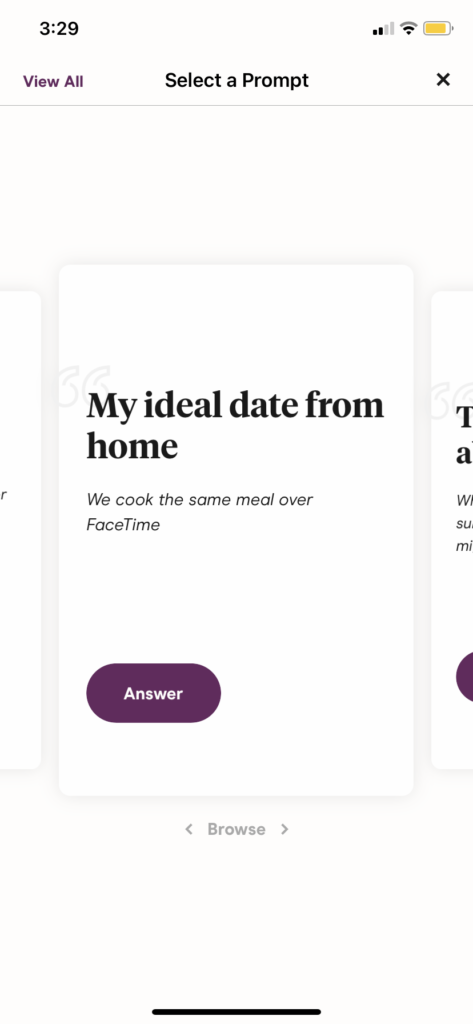

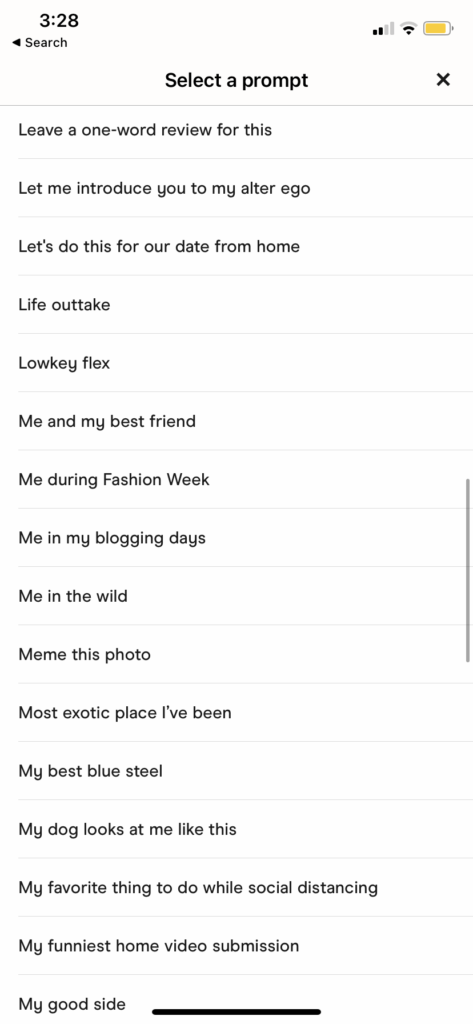

Facilitating the sharing of pandemic experiences

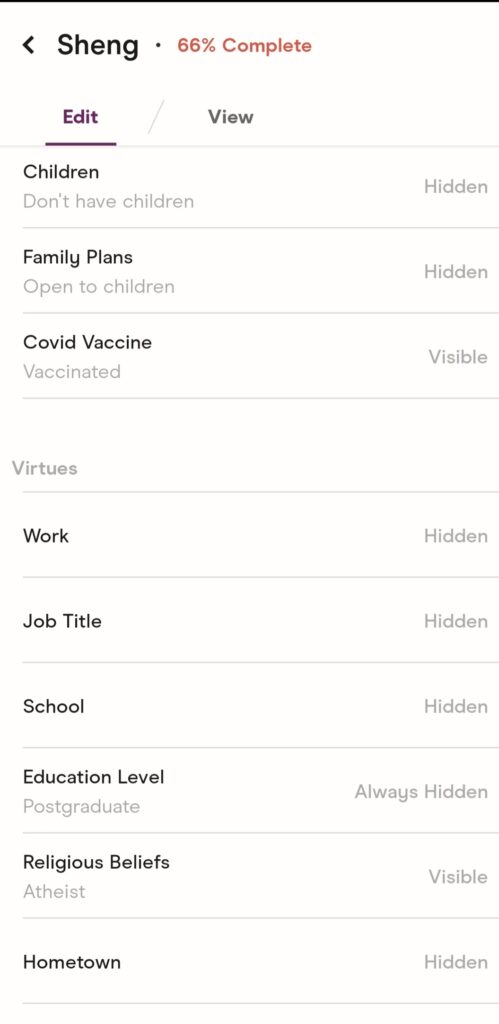

Hinge is well-known for its expansive member profiles: users can add up to three written prompts, six photos with captions (also known as prompts), ‘virtues’ (including work, education, and religion), ‘vitals’ (or basic profile information such as name, gender, and location), and ‘vices’ (with drinking, smoking, marijuana, and drug habits). After the pandemic, Hinge updated its prompts section to include their ‘ideal date from home,’ allowing users to offer virtual dating ideas. Similarly, the app added ‘let’s do this for our date from home’ in the photo caption prompt section (see figures 2 and 3).

Hinge refuses to provide users with an option to write their own prompts, whereas Tinder’s ‘bio’ option is considerably more flexible. Consequently, Tinder users created their own pandemic identities by tailoring bios to timely issues: in America, “in the early days of March, people bragged about stockpiling toilet paper and hand sanitizer. Mask-wearing became a prominent bio feature in April … The words ‘Zoom’ and ‘socially distant’ were equally prominent on Tinder as they were everywhere else online” (Molla 2021).

While Hinge specifically adapted to the pandemic by adding date-from-home prompts, Tinder’s ‘about me’ section encouraged users to get creative in the ways described above. Still, the affordances of both apps meant that they facilitated shared pandemic experiences. Users were able to express their pandemic self, find bits of humour amid a global catastrophe, and connect over commonalities in the way that they lived through it.

Easing the online dating experience

One shared experience characteristic of COVID-19 was dubbed ‘Zoom fatigue,’ used to refer to the burnout that came from being on camera and, more broadly, having the entirety of one’s experiences conducted in virtual format. Hinge and Tinder both recognized this digital exhaustion, tailoring their features to combat it in the realm of online dating.

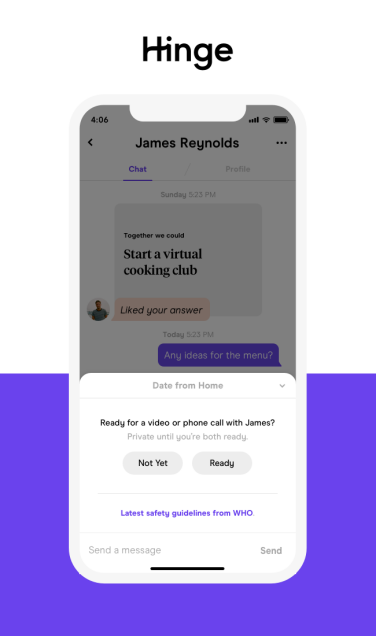

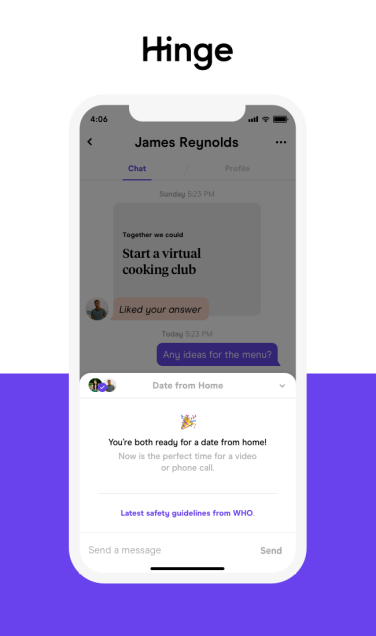

Attempting to smooth “potential friction and awkwardness,” Hinge introduced a ‘date-from-home’ feature, where people messaging receive a private pop-up menu requesting an indication of whether they are ready to call or video chat (Lovine 2020). If both parties answer that they are, they are notified via another pop-up notification and encouraged to switch over (see figures 4 and 5).

Additionally, the app launched an icebreaker feature called ‘video prompts,’ allowing users the option to select from one of eight themes and then encouraging them to pose five prompt questions to one another (Goulopoulos 2021) (see figure 6).

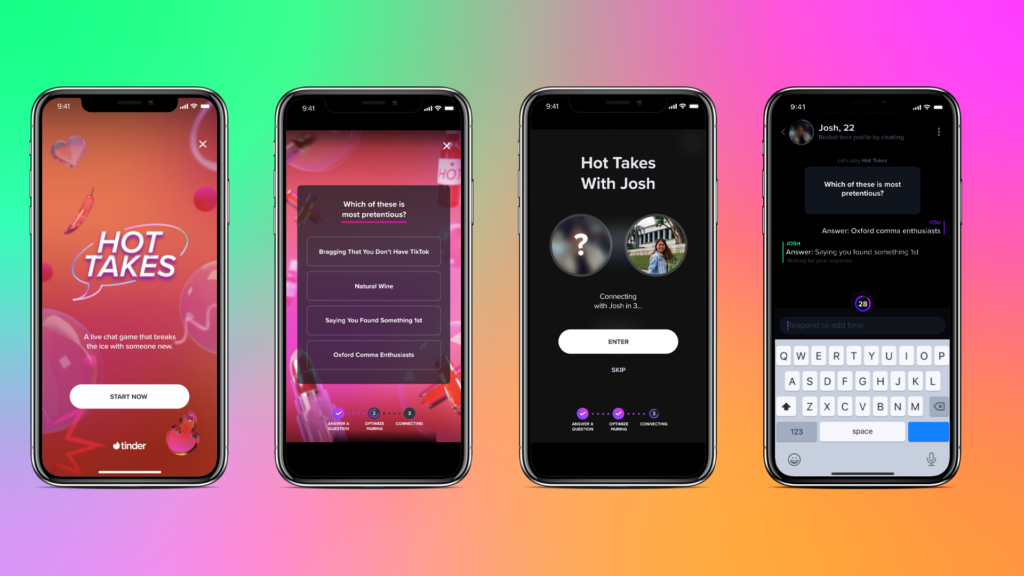

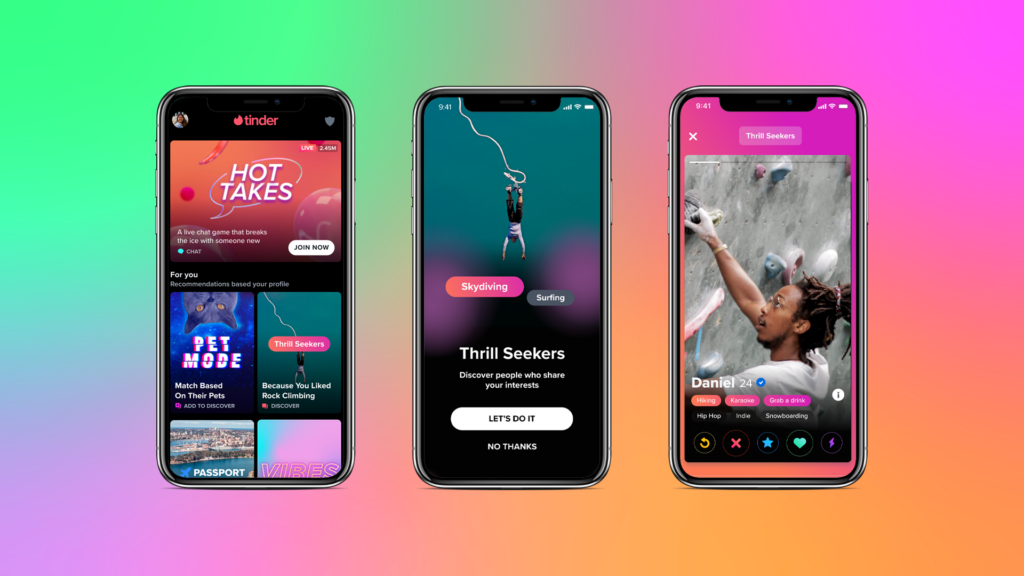

Meanwhile, Tinder turned to features inspired by their large Gen Z audience: in June 2021, the app “announced a pack of new features including the ability to add videos to profiles, and social experiences like Hot Takes and Explore” (Wynne 2021). While video posts encourage users to, as Tinder proclaims, “bring the main character energy,” the ‘hot takes’ section “gives members the opportunity to chat with someone before they match in a low-stakes session” (‘Tinder Expands Into Video and Social Experiences’ 2021). Then, as the timer counts down, each user decides whether to match with the other or move into a new round with a new person. ‘Hot takes’ is housed in the ‘explore’ section of Tinder, also born in the pandemic. As yet another feature to retain attention spans, ‘explore’ encourages Tinder users to “discover matches who share similar passions” by swiping through sections like ‘thrill-seekers,’ ‘foodies,’ and ‘entrepreneurs,’ (2021) (see figures 7 and 8).

Additionally, the goal of these changes was not exclusively to prevent digital pandemic fatigue but also to keep the user experience fresh for long-time dating app members. Tinder’s ‘passport’ feature, for example, was previously hidden behind a Tinder Plus and Tinder Gold paywall but became free for all users amid the pandemic. Removing traditional geographic radius barriers inherent to freemium dating apps, the ‘passport’ allowed members to “search by city” and change profile locations “to match up with people across the globe” for a limited time (Romano 2020) (see figure 9).

Promoting healthy pandemic habits

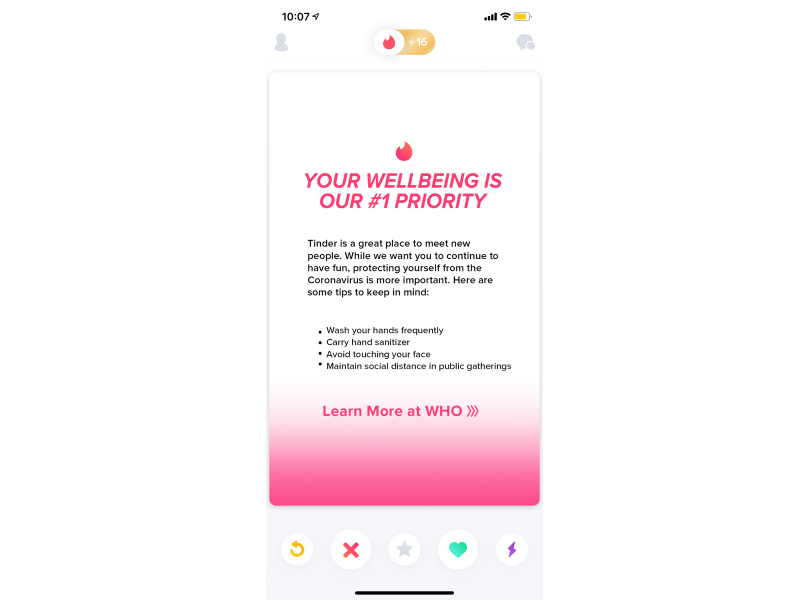

Most notable among our findings was Hinge and Tinder’s active and conscious promotion of healthy pandemic habits, including vaccination against COVID-19. Both apps requested users to follow safety guidelines, with Tinder adding a safety pop-up after “several minutes of consistent swiping” that linked to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) guidelines (Meisenzahl 2020). The screen interrupted matching altogether, effectively refusing to let the user proceed without (at least) glancing at the guidelines (see figure 10).

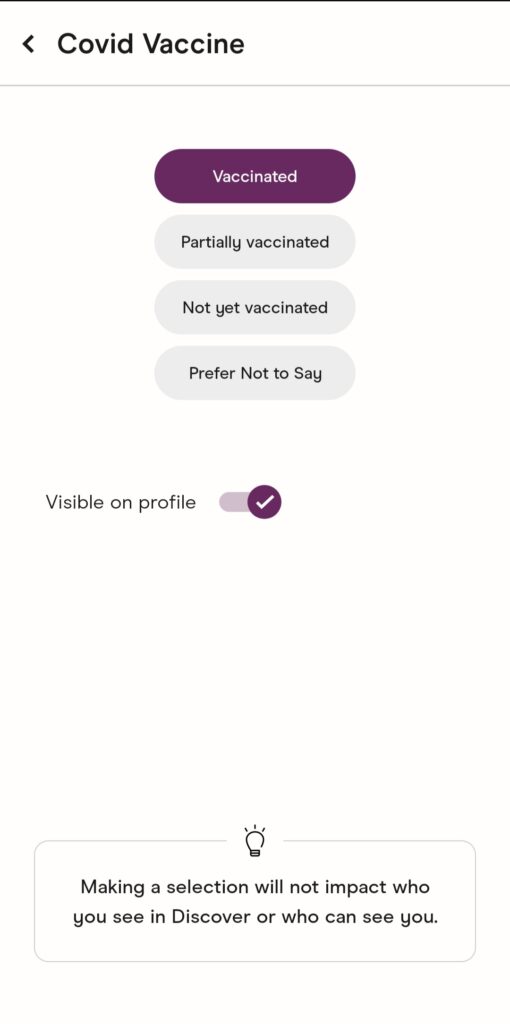

Hinge similarly included links to WHO information in parts of the app, especially those pertaining to their ‘date-from-home’ feature. The app was also quick to formalize vaccination status by adding it to the ‘vitals’ section of the user profile, allowing members to choose between ‘vaccinated,’ ‘partially vaccinated,’ ‘not yet vaccinated,’ and ‘prefer not to say’ (see figures 11 and 12).

While the app reassures its members that their selection will not impact potential matches in the ‘discover’ section and allows them the choice of making this status visible, the language in this section is noteworthy. Implicitly, these first three choices are worded to indicate that a user has the intention to get vaccinated.

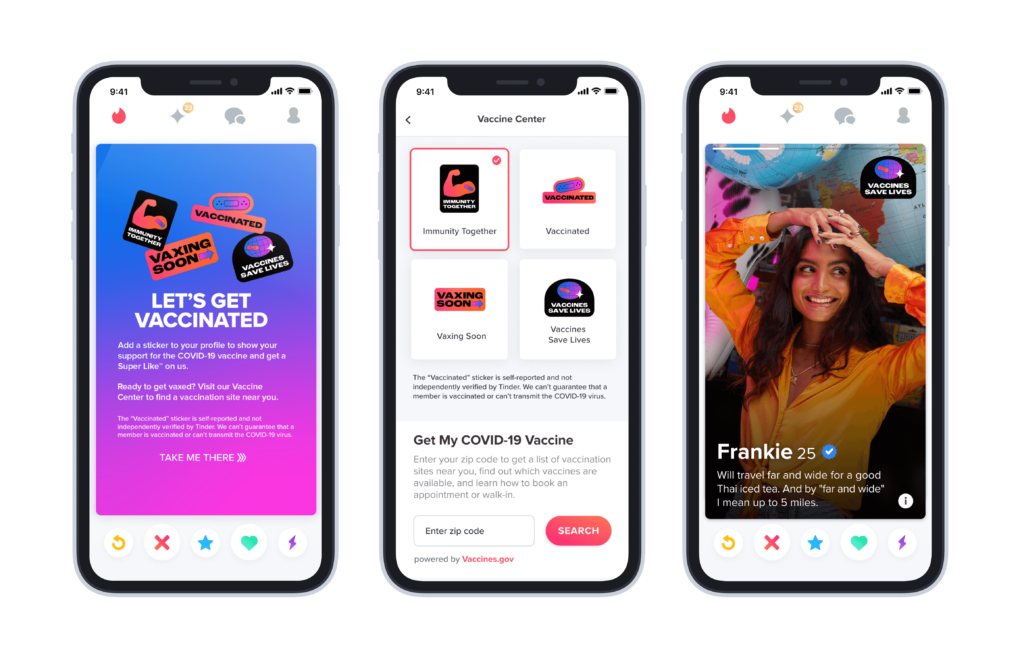

Despite vaccine status not being built into Tinder’s profile options, the platform introduced ‘stickers,’ encouraging members to “display their vaccination status and advocate for their potential matches to get vaccinated by adding new stickers” (D Cruze 2021). These included badges like ‘vaccinated,’ ‘vaxing soon,’ ‘immunity together,’ and ‘vaccines save lives,’ with loaded language similar to that of Hinge’s vaccination statuses. Tinder also opened an official ‘vaccine center’ housing these stickers, which users could visit from the app (see figure 13).

Finally, both apps encouraged users to get vaccinated and update their status through perks within the platform itself. Hinge members who participated in the vaccination received a free ‘rose’ to indicate special interest in another user, whereas Tinder members received a free ‘super like’ to similarly “help them stand out among potential matches” (GOV.UK 2021). A cry from remaining neutral in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, Hinge and Tinder adapted with their platforms, tailoring affordances to encourage their users to practice healthy habits and, ultimately, get vaccinated.

Conclusion

In this blog, we set out to examine how two of the largest dating apps, Tinder and Hinge, have adjusted to the COVID-19 pandemic. This was done through affordance analysis of both apps and supplemented by primary and secondary sources. We found that Hinge and Tinder adapted their affordances to better fit the virtual pandemic dating environment. These pandemic-related changes to features fit three overarching themes: facilitating the sharing of pandemic experiences, easing the online dating experience, and promoting healthy pandemic habits.

Further areas of study

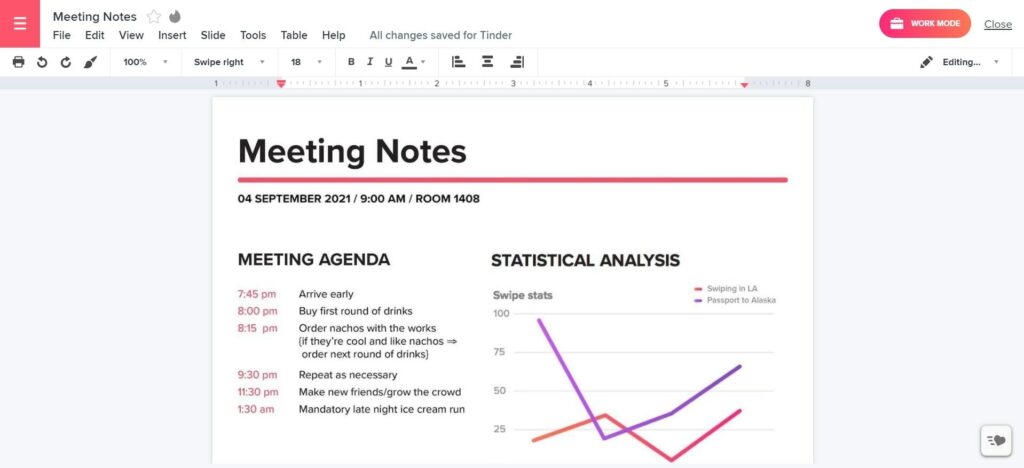

Dating apps’ response to the COVID-19 pandemic is a phenomenon that can be theorized from lenses this blog was unable to touch on. For instance, vaccination perks on dating apps were part of larger campaigns in partnerships with national governments and public health organizations in many countries. Hinge and Tinder also drastically changed their advertising strategies: the former removed all physical advertising in favour of stealth marketing on social media, and the latter turned to TikTok to market to Gen Z (Barwick 2021). Hinge users looking for deeper connections took to ‘voice noting’ on other apps such as WhatsApp, and Tinder went as far as to offer “1000 free mail-in tests for COVID-19” to 500 lucky matches so they could meet safely in person (‘Tinder Gives Away Free COVID-19 Mail-in Tests’2021). These apps are continuing to plan for the post-pandemic world as well: Tinder, for example, recently relaunched ‘work mode’ so that members returning to the office can continue to swipe from their desktops under the guise of a fake project management tool (Thompson 2021) (see figure 14).

Work Cited

Barwick, Ryan. ‘LOVE AND LOCKDOWN: DATING APPS FOUND NEW WAYS OF ATTRACTING USERS DURING THE PANDEMIC’. Adweek (2003), vol. 62, no. 2, Adweek, LLC, 2021, pp. 5.

Carman, Ashley. ‘Tinder Is Letting Everyone Swipe around the World for Free to Find Quarantine Buddies’. The Verge, 20 Mar. 2020, https://www.theverge.com/2020/3/20/21188029/tinder-passport-subscription-free-covid-19-coronavirus-quarantine.

Davis, Jenny L., and James B. Chouinard. ‘Theorizing Affordances: From Request to Refuse’. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 36, no. 4 (December 2016): 241–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0270467617714944.

D Cruze, Danny Cyril. ‘Tinder to Introduce New Covid-19 Vaccination Status Feature on Profiles’. Livemint, 15 June 2021, https://www.livemint.com/technology/tech-news/tinder-to-introduce-new-covid-19-vaccination-status-feature-on-profiles-11623766967790.html.

Department of Health and Social Care, and Rt Hon Matt Hancock MP. ‘Leading Dating Apps Partner with Government to Boost Vaccine Uptake’. GOV.UK, 7 June 2021, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/leading-dating-apps-partner-with-government-to-boost-vaccine-uptake.

‘For Everyone Who Supports Getting Their Shot, The White House and Tinder Will Help You Shoot Your Shot’. Tinder Newsroom, 21 May 2021, https://www.tinderpressroom.com/2021-05-21-For-everyone-who-supports-getting-their-shot,-The-White-House-and-Tinder-will-help-you-shoot-your-shot.

Goulopoulos, Sophie. ‘Hinge Makes Video Dating Less Awkward with New Icebreaker Prompts’. Bodyandsoul, 15 Apr. 2021, https://www.bodyandsoul.com.au/sex-relationships/relationships/hinge-makes-video-dating-less-awkward-with-new-icebreaker-prompts/news-story/9ff90e5028c83ac4c5926751a2daed4b#.pqs8m.

Light, Ben, Jean Burgess, and Stefanie Duguay. ‘The Walkthrough Method: An Approach to the Study of Apps’. New Media & Society 20, no. 3 (March 2018): 881–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816675438.

Lovine, Anna. ‘Hinge Launches “Date From Home” Feature to Help Users Do Just That’. Mashable, 7 Apr. 2020, https://mashable.com/article/hinge-date-from-home-feature.

McVeigh-Schultz, Joshua, and Nancy K. Baym. “Thinking of You: Vernacular Affordance in the Context of the Microsocial Relationship App, Couple.” Social Media + Society, vol. 1, no. 2, SAGE Publications, 2015, pp. 205630511560464-. lib.uva.nl, https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305115604649.

Meisenzahl, Mary. ‘A popup on Tinder is warning users to protect themselves from coronavirus which is “more important” than having fun’. Business Insider Nederland, 3 Mar. 2020, https://www.businessinsider.nl/tinder-warning-about-staying-safe-coronavirus-2020-3/.

Match Group. “Match Group: Quarterly Revenue 2021.” Statista, https://www.statista.com/statistics/449390/quarterly-revenue-match-group/. Accessed 24 Oct. 2021.

Molla, Rani. ‘Tinder Data Shows How Pandemic Dating Was Even Weirder than Regular Dating’. Vox, 25 Mar. 2021, https://www.vox.com/recode/22348298/tinder-data-video-online-dating-pandemic.

Plantin, Jean-Christophe, et al. “Infrastructure Studies Meet Platform Studies in the Age of Google and Facebook.” New Media & Society, vol. 20, no. 1, SAGE Publications, 2018, pp. 293–310. lib.uva.nl, https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816661553.

Poell, T., et al. “Platformisation.” Internet Policy Review, vol. 8, no. 4, Alexander von Humboldt Institute for Internet and Society, 2019. lib.uva.nl, https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1425.

Romano, Andrea. ‘Tinder Just Made Its Passport Feature Free, so You Can Match with People from All over the World’. Insider, 10 May 2020, https://www.insider.com/tinder-passport-free-lets-you-match-with-people-around-world-2020-4.

Saner, Emine. “‘People Are Looking for Something More Serious’: The Hinge CEO on the Pandemic Dating Boom.” The Guardian, 21 May 2021. The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2021/may/21/people-are-looking-for-something-more-serious-the-hinge-ceo-on-the-pandemic-dating-boom.

Sonia Livingstone and Leah Lievrouw. How to Infrastructure. SAGE Publications Ltd, 2010. lib.uva.nl, https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446211304.n13.

Stanfill, Mel. “The Interface as Discourse: The Production of Norms through Web Design.” New Media & Society, vol. 17, no. 7, SAGE Publications, 2015, pp. 1059–74. lib.uva.nl, https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814520873.

Star, Susan Leigh, and Geoffrey C. Bowker. “How to Infrastructure.” Handbook of New Media: Social Shaping and Social Consequences of ICTs, 2006, pp. 230–45, doi:10.4135/9781446211304.n11.

Thompson, Rachel. ‘Tinder Brings Back Work Mode for Daters Returning to the Office’. Mashable, 14 Sept. 2021, https://mashable.com/article/tinder-work-mode-back.

‘The Future of Dating Is Fluid.’ Tinder Newsroom, https://www.tinderpressroom.com/futureofdating. Accessed 24 Oct. 2021.

‘Tinder Expands Into Video and Social Experiences’. Tinder Newsroom, 22 June 2021, https://www.tinderpressroom.com/2021-06-22-Tinder-Expands-Into-Video-and-Social-Experiences.

‘Tinder Gives Away Free COVID-19 Mail-in Tests’. Tinder Newsroom, 16 Mar. 2021, https://www.tinderpressroom.com/news?item=122492.

Venturini, Tommaso, et al. “A Reality Check(List) for Digital Methods.” New Media & Society, vol. 20, no. 11, SAGE Publications, Nov. 2018, pp. 4195–217. SAGE Journals, https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818769236.

Weltevrede, E., and F. Jansen. “Infrastructures of Intimate Data: Mapping the Inbound and Outbound Data Flows of Dating Apps.” Computational Culture, vol. 7, 2019. lib.uva.nl, https://www.narcis.nl/publication/RecordID/oai:dare.uva.nl:publications%2Fbba18f98-6e48-4ab9-8538-824379903598.

Wynne, Griffin. ‘Your Guide to Tinder Hot Takes’. Bustle, 17 Aug. 2021, https://www.bustle.com/life/how-to-use-tinder-hot-takes.