Weight Loss Applications and Affordances: Datafying Our Bodies

Feeling Unhealthy? There’s an App For That.

The diet industry and media have long created body image insecurities in consumers (Messer et al.). Through the decades’ individuals have coveted the body ideal marketed to them and sought out products to help them lose weight. The pursuit of weight loss has been repacaged to consumers in various form, from meal replacement shakes to pills and now applications. E-health, calorie-tracking and weight-loss applications in general “provide attractive, low-cost, self-delivered way to prompt and support users to change their own behavior, with minimal or no professional contact” (Tang et al. 152). These platforms encourage users to share personal information, daily activities, food, sleep patterns, and a multitude of personal health information all in the name of ‘a healthier you’. Through the use of the walkthrough method on the Noom and Weight Watchers app and a close reading of each companies Privacy Policy, we aim to discover what data is being collected, how users are encouraged to provide their personal data and how this data is being used by these companies.

Context

“Platforms gain not only access to more data but also control and governance over the rules of the game” (Srnicek 47). While users receive weight loss plans and diet information from the platforms, the Noom and Weight Watchers also gather users’ personal information for their interest, for product improvement and in some cases sharing information to third parties. Collection of users’ data evokes questions of privacy and transparency, prompting us to look at weight loss applications, and to analyze the way they encourage users to share their personal information through examining the affordances of the platform. Privacy policies within health and fitness apps are often tough for the average user to understand or they are incorporated in the app in a way that makes it easy for users to disregard them completely (Rohan & Dehlinger 348). It is essential to understand the way these policies are incorporated into an app’s affordances and how weight loss apps are able to encourage users to share that kind of information daily.

Relevance

To access the services of both Noom and Weight Watchers, users must pay a monthly subscription; this gives most users a sense that their payment for services is the only exchange that is taking place. However, as Noom and Weight Watchers are internet-based service providers, they follow the ideals of the “gig economy” (Srnick 37).Venturini et al. state that “while digital platforms still rely on classic business models based on the exchange of information against money (through subscriptions) or against attention (through advertising), they also increasingly trade information against other information” (4197). As Noom and Weight Watches deals in a subsection of health care, they can be privy to highly personal information relating to their user’s bodies, nutritional habits, and other personal data. It is important to understand how each company persuades its users to disclose personal data and how this data is being used.

Methodology

To discover the exact way Noom and Weight Watchers (WW) encourage users to provide personal data, we will be using the walkthrough method. Created by Ben Light, Jean Burgess, and Stefanie Duguay, this method is an approach to the critical analysis of apps. This method requires the researcher to go through each step that a user would take to sign up for an application/program, everyday use, and the discontinuation of use in order to explore the way a user experiences the app and analyze the various affordances that form and are formed by cultural narratives. The walkthrough method is grounded in actor-network-theory, in this case “apps, user interfaces and functions are therefore understood as non-human actors that can be mediators” (Light et al. 6). Weight loss apps like Noom and WW are transformative, they are influenced by and influence sociocultural representations. There are many “master narratives” present in the affordances of the Noom and WW apps, which can be discovered and analyzed through the walkthrough method. While these narratives perpetuate dominant cultural norms which can be damaging to users, the affordances that push these narratives do so while prompting users to share their data. This is how apps like Noom and WW can manipulate users using master narratives and prompts within their affordances to accrue more user data. The main narrative being utilized by weight-loss applications is of course the stigma around fat bodies and the idea that women need to lose weight in order to live happy and fulfilling lives. Cognitive affordances like “Ready to Commit to Changing Your Life?” (Noom) featured on one of the registration pages, frames weight loss as life changing and necessary. This is how technology can communicate “cultural discourse” (7) while eliciting user data.

Analysis

Walkthrough of Noom

Before even setting up a personal account, first-time app visitors are asked their weight goals, the weight loss speed on a 9 point scale, gender, age, starting weight, and height. The registration and entry of Noom requests users to sign up with either email, Apple, or a Facebook account, and “choosing between these routes presents different app mediators and alters the user experience” (Light et al. 12). For instance, signing up with Facebook implies the sharing of personal information on the user’s Facebook profile, because this option initiates a push notification saying that “this allows the app and website to share information about you.” Similarly, creating an account with Apple requires sharing the email tied to the users’ Apple ID. Signing up with an email automatically gives Noom the address to send users their advertisements and promotional emails.

Noticeably, under the page of login, Noom claims that “We never sell your personally identifiable information…” (Noom) without articulating what the information is. While the login and sign-up options are evident and highlighted with bold black letters, the statement of personal information is less noticeable with smaller letters in the white-colored font at the bottom of the light background. From the interface, the platform discourages its users to read the privacy policy by hiding them from both the “symbolic representation” (Light et al. 12) design and the accessibility to the policy. The privacy statements are placed in an obscure position with underemphasized color, and this whole statement is accessible only after the users have already shared some information with Noom. Following the sign-ups, Noom continues with a long survey collecting users’ health information. One question asks about whether the user is at risk of any disease. In between each section of the survey, there is a break that encourages users to continue answering, through repetitively telling the users that the aim of the survey is to “customize your plan” and the service is personalized because it is “based on your answers.”

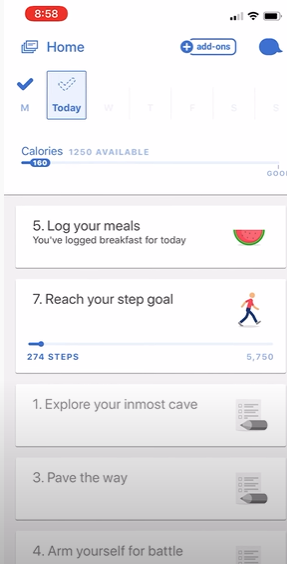

The finishing of the survey leads to the start of the trial. Regarding everyday use, Noom expects the users to weigh themselves every day to create a weight graph. Besides recording users’ food and calories, Noom also records the number of steps as an indicator of exercise amount shown in a linear graph. The whole interface constructs the governance of Noom that “manages and regulates user activity” (Light et al. 10). The list of to-do prompts users to complete them, and when it is done it turns grey, consistent with the tick mark on each date above. The ease of access and user interface arrangement together encourage the user to continue using and sharing their data, as they reinforce the impression of “customized” and “personalized” in the user interaction process.

Weight Watchers Walkthrough

When opening the app a push notification appears asking the user for permission to track their activity on other companies’ apps and websites. This prompt was implemented by iOS 14.5 giving the user the choice to be tracked across platforms or not (Boyd). In order to sign up for Weight Watchers, users must fill in a personal assessment which aims to “understand a little bit about how you think and feel, and also some basics like your height and current weight” (“Weight Watchers”). This assessment is described by the website as “look[ing] at all aspects of your wellness to deliver a truly personalized approach” (“Weight Watchers”). Directly from its introduction to the user, the WW Weight Watchers Reimagined application frames itself as both a weight loss and a wellness program, emphasizing its focus on wellness. On the third question of the assessment it asks for the users first and last name, sex: Female or Male, current weight and height. The assessment starts by asking questions like “How do you generally feel?” And “When it comes to your home life, which sounds the most like you?” With 3-6 multiple choice style answers. There are 5 sections with 5-6 questions each, covering mental health, the user’s relationship with food, exercise and sleep. After each section, the app explains how the program will be able to improve the user’s lifestyle, prompting users to continue the assessment to solve the listed issues. This personal approach is very similar to Noom as it convinces users to provide more information in order for the program to become more personalized. After filling out the assessment four icons labelled Nutrition, Activity, Sleep and Mindset are shown with horizontal lines filled based on what areas need a “boost”. Each category has a description outlining what needs to be improved on and how the app can help followed by the option to “Try for free and subscribe”. After providing the personal information through the assessment the Membership page introduces users to the Privacy Policy and Terms and Conditions. Like Noom, WW’s design does not prioritize making these pages accessible. These are at the bottom of the page that requires the user to scroll down to view as they are choosing between a Digital plan and a “NEW! Digital 360” plan. If the user chooses the Digital 360 plan without scrolling they would not see them at the bottom of the page. After choosing one of the memberships users are prompted to check a box that “acknowledge[s] that you have read and agree to be bound by Terms and Conditions, Subscription Agreement, Privacy Policy, Notice of Privacy Practices” (WW). Having multiple options coupled with the Privacy Policy likely would discourage the user to attempt to read it as it can be overwhelming. Unlike some apps it is not required to scroll through the Terms and Conditions page to confirm it has been read.

Similar to Noom, the WW program encourages users to track everything they eat, what activities they do and has also partnered with the app Breethe in order to encourage mindfulness programs. Food tracking includes food from restaurants and chains like Subway, Starbucks and McDonalds.Weight Watchers users log their weight once a week and are prompted to log all their meals and snacks. Exercise is logged in order to gain points that can then be used towards food items. Depending on their plan they receive a specific amount of points per day that are then diminished by food that is attributed specific points. They have an extra weekly allowance of points as well to make it more flexible. When certain goals are reached WellnessWins are earned which can then be used to “purchase” rewards. Items such as memberships to cooking classes or fitness programs are added incentives for users to track their progress daily. WW has evolved their narrative around weightloss to put more emphasis on wellness. This also means that the information they collect from users goes beyond diet and physical activity. Users can track their mindset through programs affiliated with the app as well as track their sleep. They are encouraged to share every aspect of their life with the app as well as other users through WW Connect, which is a Facebook style platform on the app for sharing goals and recipes with other members. The various programs within the app have permitted WW to ask more and more from their users in terms of freely given data.

Privacy Policy

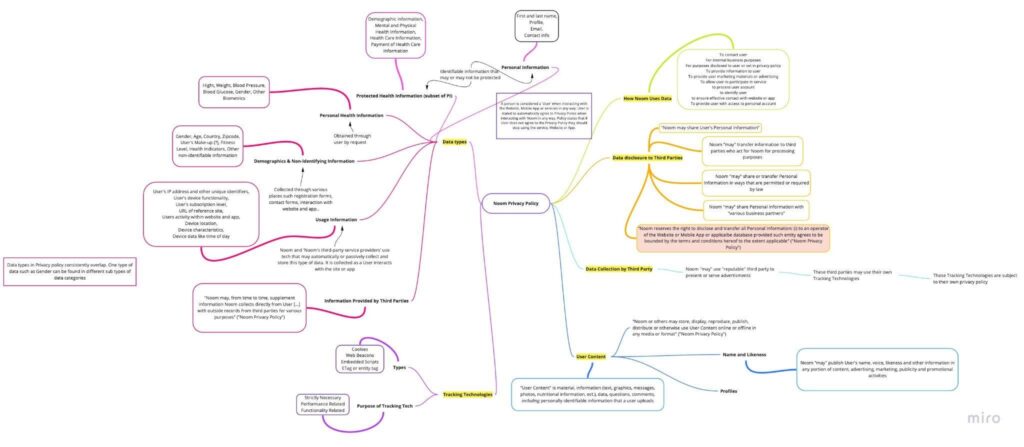

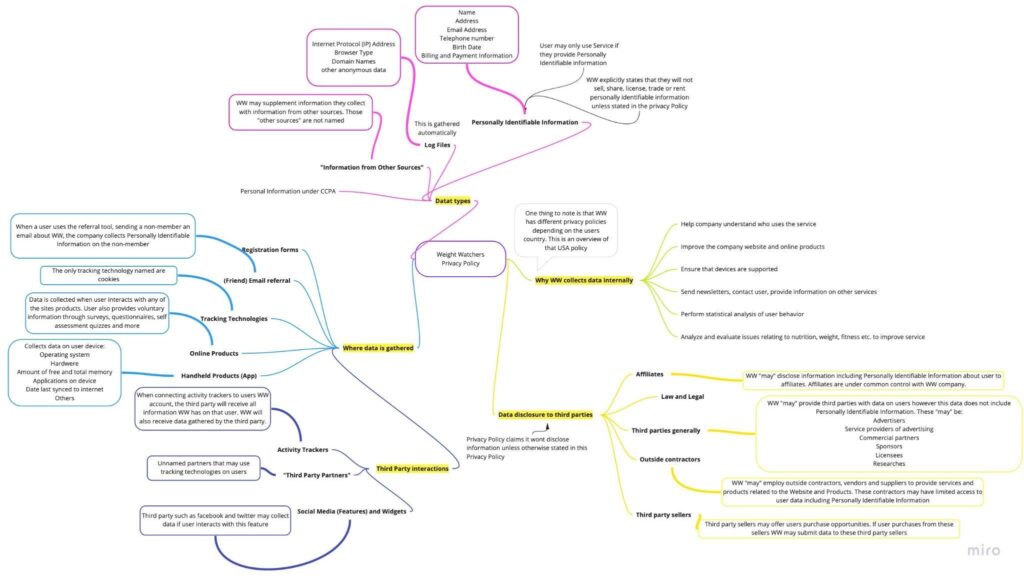

To obtain an overview of how Noom and Weight Watchers gather, store and handle user data, we conducted a close reading of each company’s Privacy Policy. From this close reading, two mind maps were created, visualizing what each company disclose about user data according to their Privacy Policy.

Discussion

Noom constructs certain ethnicity and culture of its users

The Noom application is available in the Chinese account’s apple store while WeightWatchers’ application can not be found there, but interestingly, even if the application is downloaded from the Chinese Apple store, the language is still automatically English. Noom provides non-western languages on the website, while WeightWatchers automatically directs the user to the website of the user’s country, which are dominantly Western countries, as Israel is the only Asian country available as a choice. Additionally, Noom’s survey and the everyday use of food search or recipes follow Western food culture. For instance, when asking about what do users eat for lunch and the three choices available are salad, sandwiches or wraps, and others. The “other” option serves as a refusion to non-Western cultures. In other words, it refuses and discourages non-Western cultures by setting the language and food culture barriers and embeds “cultural discourses” (Light et al. 11), demonstrating the construction of users’ ethnicity.

Weight Watchers’ engages various programs to obtain more data

WW has integrated wellness programs and sleep tracking along with tracking weight, food intake and physical activity. Every action a user takes during the day (even while they are sleeping) is recorded. They have a social media platform within the app (WWConnect) that allows users to post and interact with other people’s content. This means that there is personal health data generated by the user as well as content on the platform. These programs allow the app to become immersed in every aspect of the users’ life, from what they have in the fridge to if they woke up in the middle of the night. The Privacy Policy that would allow users to be aware of how this information is being collected, and used is inconspicuous on the app’s interface.

Getting Lost in the Privacy Policy

According to its Privacy Policy, “Noom obtains User’s consent to Noom’s information storage or collection Tracking Technologies by providing User with transparent information in Noom’s Privacy Policy” (“Noom Privacy Policy”). This redundant bias to user satisfaction phrasing is abundantly seen in Noom’s Privacy Policy. Noom uses vague language like “may” and “from time to time” and does not name any of the other entities who have access to Noom user data, simply labeling them as third parties.

As seen in the Noom mind map, data is collected at every point in the user experience and even in manners that are not evident at first glance, such as information about the user devices. The same can be said of Weight Watchers. However, its Privacy Policy specifies further who the third parties could be by defining them as affiliates, social media sites, activity tracker companies, etc.

Weight Watchers state “by using our Website or any of our products, offerings, features, tools or resources that we provide on our Website [..], including our products or offerings for personal digital assistants or other handheld or mobile devices […], you agree to the terms of this Privacy Policy” (“Privacy Policy”). Something similar is also stated in Noom’s Privacy Policy with the addendum “If you do not consent to the terms of the Privacy Policy, please do not access or use the Service” (“Noom Privacy Policy”). This point may not be clear to the average consumer of both Noom and Weight Watchers. This is particularly worrying in the case of Noom, who provides visitors of its app with a lengthy questionnaire to fill out even before the user has created a profile.

Both Privacy Policies state that they do not share user information (particularly identifiable user information) with third parties unless otherwise stated in the Privacy Policy. This is a redundancy because in multiple points in Noom and Weight Watchers, they do disclose that certain information is shared with third parties for various reasons.

Though both Privacy Policies are not transparent with the full extent of data gathered, stored, and shared and who exactly are the third parties mentioned, it is clear that data is generated at every point of the user experience, and this data is shared to a multitude of third parties.

Conclusion

In conclusion, both Weight Watchers and Noom collect users’ data more than diet and physical activity information through interface design and platform affordance. The language they use to persuade users to share their data includes for the purpose of users’ wellness and personalized health plans. Likewise, the language in the private policy of both platforms is ambiguous and sometimes contradictory, hiding the specificity of privacy questions.

Works Cited

Boyd, Colin. “Should I Allow Apps to Request to Track on My Iphone? Here’s the Truth!”

Payette Forward, 11 May 2021,

https://www.payetteforward.com/allow-apps-to-request-to-track-on-iphone/.

“How to Take the MyWW+ Personal Assessment.” About the MyWW Personal Assessment

WW USA, Weight Watchers, 28 Sept. 2021,

https://www.weightwatchers.com/us/blog/weight-loss/myww/assessment.

Light, Ben, et al. “The Walkthrough Method: An Approach to the Study of Apps.” New Media &

Society, vol. 20, no. 3, Mar. 2018, pp. 881–900. DOI.org (Crossref),

https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816675438.

Messer, Mariel, et al. “Using an App to Count Calories: Motives, Perceptions, and Connections

to Thinness- and Muscularity-Oriented Disordered Eating.” Eating Behaviors, vol. 43,

Dec. 2021, p. 101568. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2021.101568.

“Noom Privacy Policy.” Noom. 2018, https://web.noom.com/noom-privacy-policy/. Accessed 17

October 2021.

“Privacy Policy.” Weight Watchers, 9 March 2021,

https://www.weightwatchers.com/us/privacy/policy. Accessed 17 October 2021.

Rowan, Mark, and John Dehlinger. “A Privacy Policy Comparison for Health and Fitness

Related Mobile Applications.” Procedia Computer Science, vol. 37, 2014, pp. 348–355.

Srnicek, Nick, and Laurent De Sutter. Platform Capitalism. Polity, 2017.

Tang, Jason, et al. “How Can Weight-Loss App Designers’ Best Engage and Support Users? A

Qualitative Investigation.” British Journal of Health Psychology, vol. 20, no. 1, Feb.

2015, pp. 151–71. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12114.

Venturini, Tommaso, et al. “A Reality Check(List) for Digital Methods.” New Media & Society, vol. 20, no. 11, Nov. 2018, pp. 4195–4217, doi:10.1177/1461444818769236.