A MEDICAL DOSE ON TIKTOK: AN ANALYSIS OF THE GROWING EDUCATIONAL SUB-GENRE

New Media Research Practices

WG5-A2 Final Project

Carla Roman, Lynn Kastalio, Alexia Miehm

ABSTRACT

As of September 2021 popular video-sharing app TikTok has reported more than one billion users (TikTok Newsroom 2021). This “global community” presents itself as an app for entertainment, laughter, discovery, and education. This paper investigates how TikTok serves as a platform for education. Of the many educational communities on TikTok that the platform has partnered with to bring learning material to the app (TikTok Newsroom 2020), this paper focuses on the content produced by medical professionals. Utilizing their material, we explore the positive and negative aspects of TikTok as a provider of educational information related to the field of medicine, specifically as it relates to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

MEDICS ON TIKTOK

In 2020 New York Times journalist Emma Goldberg wrote “Doctors on TikTok Try to Go Viral” (Goldberg 2020) that inspected the community of medical professionals on TikTok. In the article, Goldberg interviewed TikTok executive Gregory Justice who publicly supported the growing medical community on the platform. Justice said “it’s been inspiring to see doctors and nurses take to TikTok in their scrubs to demystify the medical profession” (Goldberg 2020). During a global pandemic, medical staff used TikTok to document their grueling work as they treated those who contracted COVID-19.

WHO IS WATCHING

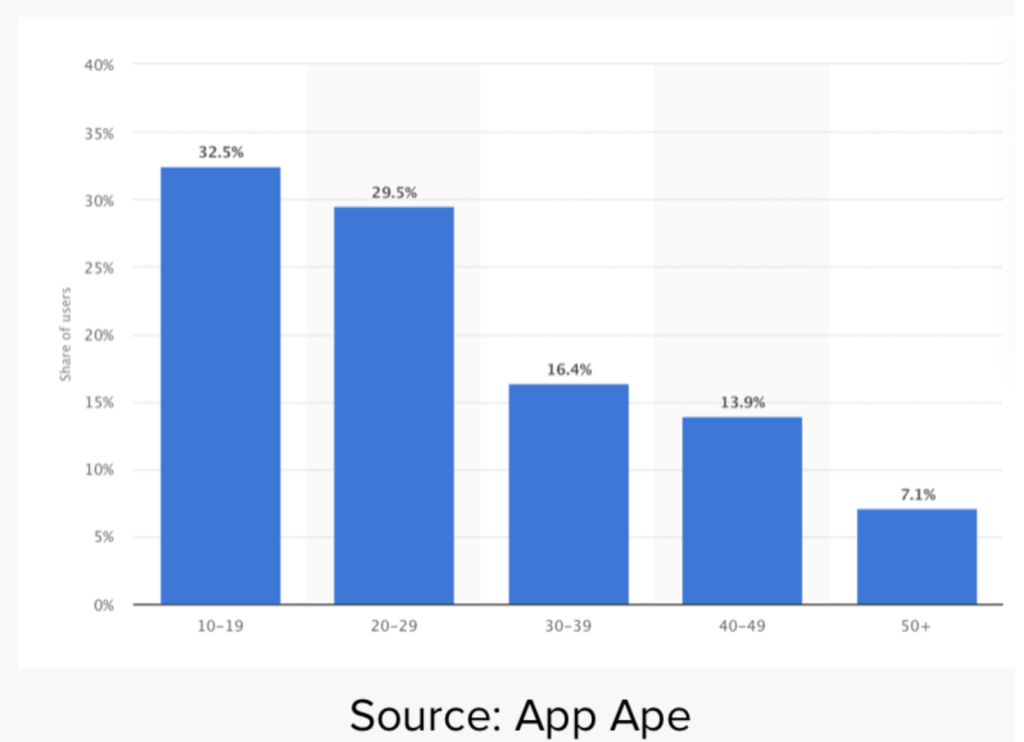

For whom is this content mainly produced? According to recent statistics (Statistica Research Department 2021), the main demographic of TikTok users in the United States ranges between the ages of ten to thirty. More specifically, 32.5 percent of users are 10 to 19, and 29.5 percent are 20 to 29 years of age (Statistica Research Department 2021). This data proves that the content produced by medical professionals is presented to an expansive demographic of largely impressionable individuals.

THE VIRAL STORM

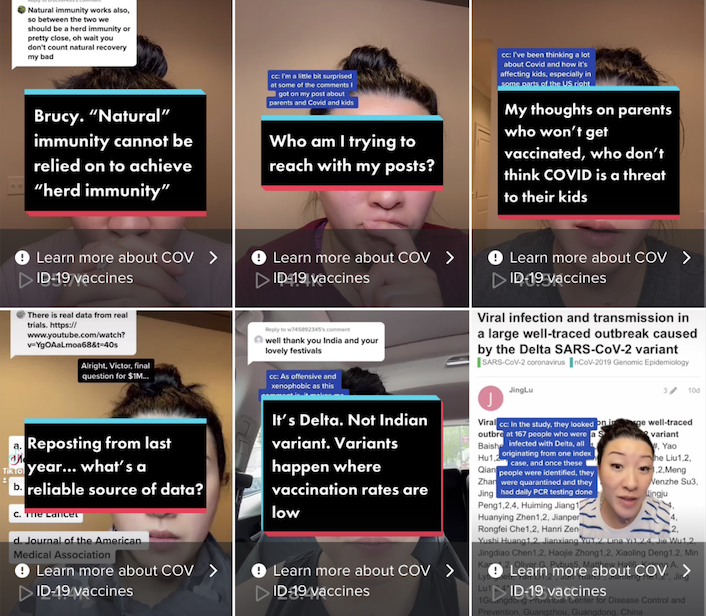

The rise of both COVID-19 and the popularity of TikTok provided a unique opportunity for the medical community. With the uncertainty of the pandemic, the novelty of the virus, and the unprecedented quarantines and closures, TikTok users turned to creators on the app for a source of guidance with respect to the virus. The accounts and COVID-19 related content from experts such as Nurse Practitioner Christina Kim took off on TikTok. Sharing her first video on TikTok in May of 2020, she has since used her background in nursing to discuss the concept of herd immunity, research on masks, vaccine trials, and the long-term complications of the virus. To-date, Kim’s TikTok account has over 340,000 followers and her COVID-19 related content has views in the ten-thousands. To-date, the hashtag #DoctorsOfTikTok has 2.3 billion views, #medicaltiktok has 556.9 million views, and #LearnOnTikTok has 185.5 billion views. However, education regarding COVID-19 has become a double-edged sword within the expert medical community on TikTok.

CONFLICTING NARRATIVES & EDUCATION

As of recently, TikTok has seen a rise in videos from medical professionals supporting unconventional and unproven methods in the treatment and prevention of COVID-19. This has created a growing divide within the medical community. These videos, from the accounts of TikTok-verified medical experts, are ‘educating’ viewers on alternate treatment options for COVID-19 that contradict CDC guidelines. As TikTok champions behind internal campaigns such as #LearnOnTikTok to position themselves as educators (Thoensen 2020), this divide within the medical content producers is creating a controversial and unchecked learning environment that could result in real-world consequences.

POINT OF INQUIRY

Our research seeks to highlight how TikTok can be an untrustworthy educational resource especially in the fields of health and medicine. This paper will follow several verified medical professional TikTok creators in order to demonstrate how this genre was fostered to serve as a reliable educational resource. We aim to present the potential implications that could stem from this unmonitored medical subculture as it relates to the spread of misinformation related to COVID-19.

METHODOLOGY

“The walkthrough method establishes a foundational corpus of data upon which can be built a more detailed analysis of an app’s intended purpose, embedded cultural meanings and implied ideal users and uses” (Light et al., 2016).

Our study will make use of The Walkthrough Method (Light et al. 2018) to explore the medical subculture on TikTok. This method functions on two levels. In order to establish TikTok as an environment we will identify and describe “its vision, operating model and modes of governance” (Light et al., 2018). By examining each of TikTok’s functions, we have the ability to directly engage with the platform’s interface. Our goal is to gain an understanding of the embedded cultural phenomena and technological mechanisms within the app (Light et al. 2018). The walkthrough method suggests focusing on three key components of the app: the vision, the operating model, and governance. These components will allow us to determine how TikTok has fostered a growing medical genre, and resulting educational implications. Furthermore, by utilizing affordance theory in combination with our walkthrough, we will explore how the platform allows and encourages audience members to interact with verified medical content creators and those who claim to be, and how the platform affords pseudo-medical diagnosis from doctors for viewers.

ANALYSIS: VISION

According to Light et al, the vision of an app “involves its purpose, target user base, and scenarios of use, which are often communicated through the app provider’s organizational material” (Light et al., 2018). As of recent TikTok’s has expanded its famous mission statement of ‘inspire creativity and bring joy’ (TikTok), to present itself as a platform for both entertainment and education. This new vision is clearly mirrored in both the content creators and the user perception and interaction with the new content.

Medics are now valuable content creators that utilize the platforms to spread (mis)information and educate. With 42% of the total user demographic, being between the ages of 18 and 24, and 27% of the total user demographic being between the ages of 13 and 17 (Li et al, 2021), TikTok is reaching a young and influential audience. This is important to note, considering that content spread and created on TikTok is user-generated – meaning doctor or not, the app provides a platform for people to spread medical advice, and target an unsuspecting user demographic. Furthermore, the interface of TikTok affords users to share content swiftly and easily.

ANALYSIS: SHAREABILITY & DISCUSSION

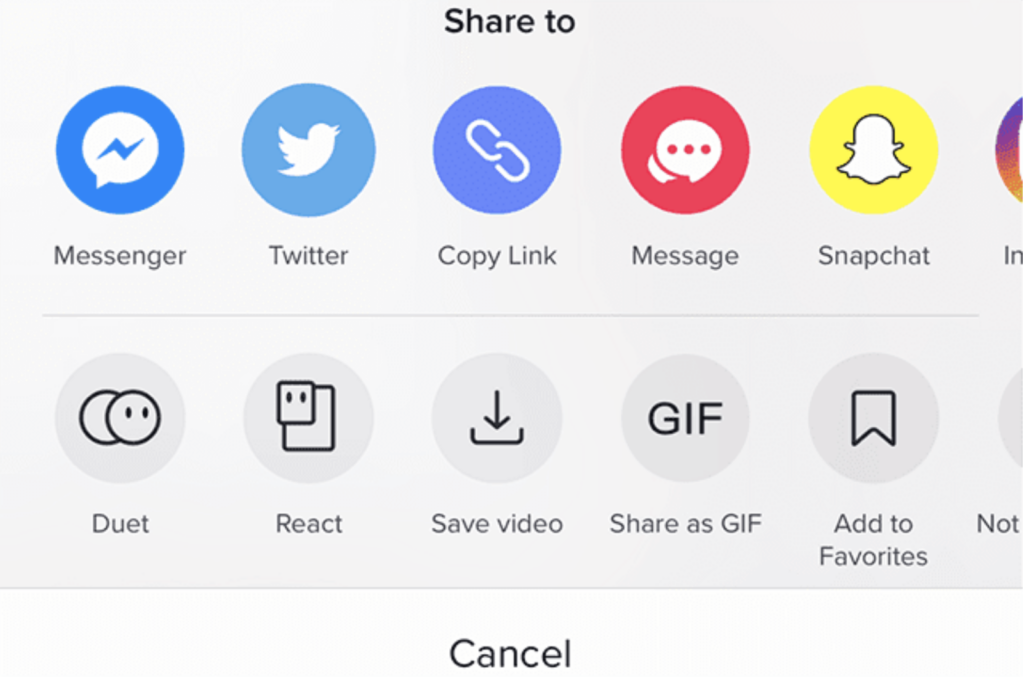

The content on the main page of TikTok and the ‘For You Page’ (FYP), can be shared with others internally, to other social platforms, via SMS or e-mail with one-click. TikTok’s interface design encourages content to be shared within the app and networked world. This system encourages virality, however, it is also responsible for the spread of information and misinformation.

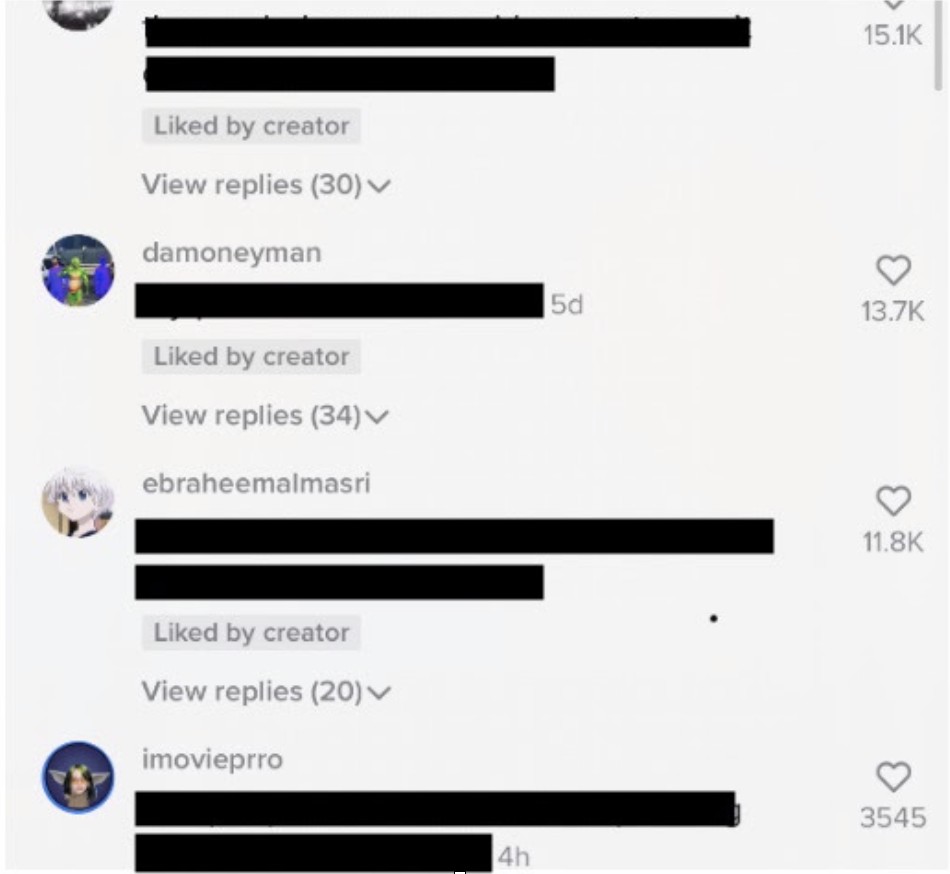

The spread of information and direct interaction between content creators and users is further fostered through the ‘comment’ section. Each TikTok video features a ‘comment’ section, which encourages discussion amongst viewer and creator. TikTok as a platform affords communication further, by allowing viewers to upvote comments and like comments. The most liked comments appear at the top of the section – no matter what it may say.

Furthermore, content creators are able to ‘like’ comments, which makes the given comment stand out further as an icon that states ‘liked by creator’ appears. Thus, the ‘comment’ section affords the spread of (mis)information further, by allowing users to comment on the information provided within a video, and by spreading this information further. This outlines a problematic feature within the ‘comment’ section, particularly in relation to dangerous or problematic medical advice, one of TikTok’s key genres. These online comment-discussions on TikTok related to medical content can result in harmful behavior in real life. To control the misuse of the comment section, TikTok allows content creators to limit comments, or to discard the function entirely. It is evident that TikTok as a platform gives the creator a large amount of power through the comment section, however, one of the key features that afford power to the creator is the ‘verified’ checkmark on a user account.

AFFORDANCES WITHIN TIKTOK FOR EDUCATORS

“A site’s design makes a normative claim about its purpose and appropriate use that both demonstrates an understand of users and builds a set of possibilities into the object” (Stanfill, 2015).

When we view TikTok through the lens of affordances – we begin to understand what the app’s design and structure allows for content producers. Our focus will be on pointing out the design features on TikTok that afford content producers a sense of credibility, professionalism, and belonging within the genre of educators on TikTok. Specifically, we will explore the accounts of verified medical professionals and describe the affordances that position their content as educational, reliable, and factual.

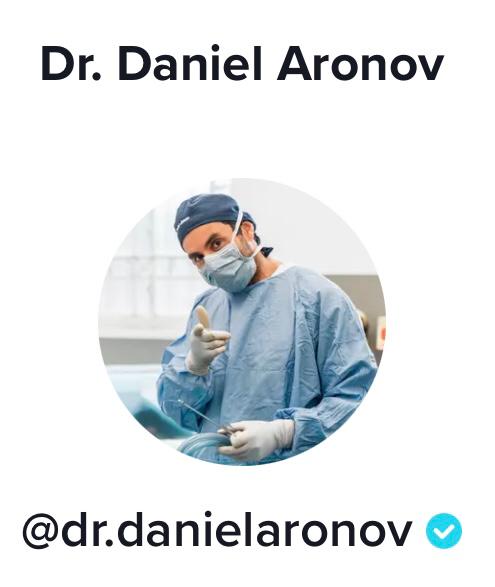

THE VERIFIED BADGE

On TikTok you will see accounts with a ‘verified badge’ next to their username. This verification badge allows audience members to recognize that the content creator they are interacting with is from a notable and authentic figure (TikTok Newsroom 2019). TikTok grants creators with this badge after their identity has been confirmed (TikTok Newsroom 2019). This includes verifying the content creator’s portfolio (resume) if they are identifying as MDs, CNPs, FNPs, PhDs, NPs, etc. According to TikTok, the verification badge is meant to “help users make informed choices about the accounts they chose to follow.” (TikTok Newsroom 2019). A verified badge allows audience members to view the account as credible and believe that the information they are receiving regarding medicine, health, or COVID-19, is truthful.

However, becoming verified– as medics or experts on TikTok—can be both helpful and harmful. With the added sense of credibility, medical educators on the platform hold significant weight when it comes to influencing the health choices of the app’s users. While many verified medical accounts teach viewers about the medical field, providing COVID-19 information, and even debunking conspiracies behind COVID vaccines, other verified accounts use the platform to spread their own, alternative, medical pedagogy and advice.

TIKTOK IDENTITY: AFFORDANCES IN USERNAMES

“Cognitive affordances facilitate processing information and are therefore closely tied to the social act of meaning-making. Cognitive affordances relate to naming, labeling, and/or site taglines and self-descriptions” (Stanfill 2015).

Every content producer on TikTok needs to have a registered account and username. They also have the option to write a short bio and include a profile image. Since the username on your account is the first thing users see, the username affords the viewer an understanding of the content to expect from you. Many of the accounts on TikTok that produce educational content around health and medicine have usernames reflecting their claim to medical knowledge. Many account names start with Dr. or feature AP (for assistant physician), or have their field of practice in their name. Allowing TikTok users to use their professional title in their account name, affords a sense of expertise for the viewer engaging with the account. Viewers and browsers on TikTok that open the feed of someone with a username like “thepsychdoctormd” make meaning from the name and conclude that the content will be from a psych doctor or will have videos related to psychology.

PROFILE IMAGES

“That affordances vary by degree indicates…how affordances work…This how can be packaged into a suite of interrelated mechanisms. We propose that artifacts request, demand, allow, encourage, discourage, and refuse” (Davis and Chouinard, 2016).

If we view the profile image feature on TikTok as a “request” in the way that Davis and Chouinard position Facebook’s profile image as a request, we realize users do not need to have a picture to have an active account. Many accounts on TikTok exist without a profile image, but if we focus on the educational medical community, we see that most have a profile image. Medical accounts on TikTok having a profile image could be for a few reasons, including verification purposes, or because of the “implicit social pressure from others in their networks” (Davis and Chouinard, 2016). A profile image on TikTok then serves several purposes for medical content creators. Without a profile image medical experts remain unverified and therefore perceived with less credibility. Many medical professionals on TikTok appear in scrubs or use a professional headshot for their profile image. This adds another layer of professionalism and credibility to the account.

POTENTIAL PITFALLS

Although TikTok provides an excellent environment for educators, scholars, and professionals to teach on their platform, community surveillance is needed. Now that TikTok promotes themselves as a place to learn (under the hashtag #learnonTikTok), further inspections should be undergone regarding the aforementioned affordances. TikTok members could be misled by a given content creator’s username. There have been instances where individuals pose as a Doctor, AP, OBGYN, etc., through their username. It is also possible for individuals to be misled by creators who sport medical attire in their profile picture but have no affiliation or training within professional health studies. In these circumstances, viewers may be deceived into believing that they are learning from medical professionals.

IVERMECTIN – THE FIRST OF A GROWING DANGER

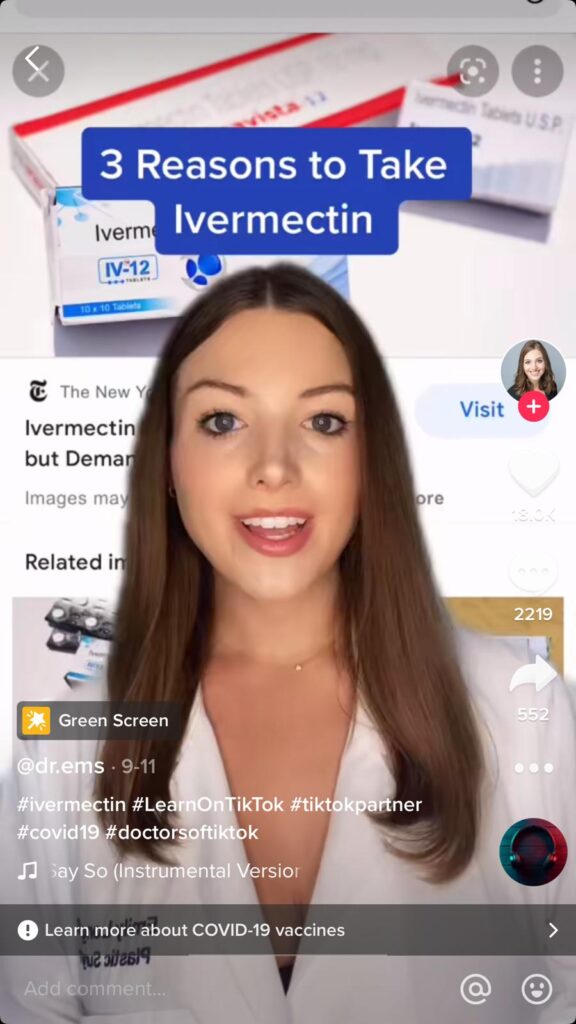

Recently, news has been circulating regarding a certain drug that some claim to be a ‘miracle cure’ (Furlong 2021) for COVID-19: Ivermectin. Ivermectin is an anti-parasitic drug used to treat roundworms and other parasites (FDA 2021). The drug has two forms for use. One is used by veterinarians and the other form is made and used for human consumption (FDA 2021). Unfortunately, Ivermectin as a COVID-19 cure spread on TikTok.

A DOSE OF IVERMECTIN ON TIKTOK

This year, content surrounding Ivermectin on TikTok became a health issue. Ivermectin as a treatment for COVID-19 has not been approved by the FDA (FDA 2021) or CDC (CDC Health Alert Network 2021). Yet, on TikTok, verified accounts of medical professionals have produced video content in support of the drug. In August 2021, the Rolling Stone published an investigative piece titled, “TikTok is Full of Videos of People Promoting Ivermectin, the Horse Deworming Medication Falsely Touted as a Covid Cure” (Dickson 2021). The investigation, led by reporter EJ Dickson found that TikTok was circulating pro-ivermectin video content. The investigation also led to the discovery of accounts from professionals, such as Dr. Pierre Kory, who were actively promoting the false narrative of ivermectin as a cure for COVID-19.

Since the article’s publication, TikTok confirmed that the accounts of medical professionals promoting ivermectin as a treatment for COVID-19 violated community guidelines. TikTok subsequently removed the content from the platform and suspended such accounts (Dickson 2021). However, the damage was done. Videos with the hashtag #ivermectin4covid and #ivermectinworks had already garnered more than 997,000 views according to Dickson.

When TikTok afforded credibility to medical educators on their platform via the verified badge, they failed to consider that not all medical professionals would have the same views on treatment plans related to viruses such as COVID-19. In this instance, the validity that TikTok afforded to medical content creators proved to be harmful to the app’s viewers.

CONCLUSION

Our essay has provided evidence that demonstrates TikTok’s growing medical and educational community. We chose to focus on the community of educators, the medical subculture, which we believe held the greatest influential presence during the ongoing COVID-19 epidemic. By walking through this genre of TikTok content, we were able to exhibit various affordances that foster a relationship of trust between medical content creators and their viewers. Some of these affordances include one’s profile image, and their username. Exploring these affordances allowed us to break down the reasons why TikTok allows for the spread of misinformation such as discussions related to ivermectin within their medical community. Due to the ease of medical professional impersonation and rapid spread of information it is clear that TikTok can be a problematic environment for education. Further, internal content and creator surveillance should be appropriately reviewed in the medical subculture to prevent the rapid spread of false information. Additionally, it is crucial that the platform takes steps towards establishing clear guidelines denoting how it plans to exist as “a place to learn” (TikTok Newsroom 2021).

References

CDC Health Alert Network. “Rapid Increase in Ivermectin Prescriptions and Reports of Severe Illness Associated with Use of Products Containing Ivermectin to Prevent or Treat COVID-19.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 26 August 2021, https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/2021/pdf/CDC_HAN_449.pdf. Accessed 19 October 2021.

Christina NP. https://www.tiktok.com/@christinaaaaaaanp?lang=en. Accessed 18 October 2021.

Davis, Jenny L., and James B. Chouinard. “Theorizing Affordances: From Request to Refuse.” Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, vol. 36, no. 4, SAGE Publications, 2016, pp. 241–48, doi:10.1177/0270467617714944.

Dickson, EJ. “TikTok Is Full of Videos of People Promoting Ivermectin, the Horse Deworming Medication Falsely Touted as a Covid Cure.” Rolling Stone, 26 August 2021, https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-news/tiktok-covid-cures-ivermectin-horse-deworming-medication-1216268/. Accessed October 19 2021.

“’Don’t do it’: Dr. Fauci warns against taking Ivermectin to fight Covid-19.” CNN, 29 August 2021, https://edition.cnn.com/videos/health/2021/08/29/dr-anthony-fauci-ivermectin-covid-19-sotu-vpx.cnn. Accessed October 20 2021.

Dr. M.C. Haver. https://www.tiktok.com/@galvestondiet?lang=en. Accessed 18 October 2021.

Food and Drug Administration. “Why You Should Not Use Ivermectin to Treat or Prevent COVID-19.” FDA, 3 September 2021, fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/why-you-should-not-use-ivermectin-treat-or-prevent-covid-19. Accessed 19 October 2021.

Furlong, Ashleigh. “The rise and fall of a coronavirus ‘miracle cure’.” Politico, 30 March 2021, https://www.politico.eu/article/rise-and-fall-of-coronavirus-miracle-cure-ivermectin/. Accessed 20 October 2021.

Goldberg, Emma. “Doctors on TikTok Try to Go Viral.” The New York Times, 2020.

Hipfl, Brigitte, and Elena Pilipets. “Digital Youth Assemblages: Affective Entanglements of Sharing (Anti-)Selfies on Instagram.” Digital Culture, New Media, and Youth. Digital Practices and Cultures of Youth, vol. 44, no. 2, Medien Journal, 2020, pp. 19-32, doi: 10.24989/medienjournal.v44i2.1948.

Light, Ben, et al. “The Walkthrough Method: An Approach to the Study of Apps.” New Media & Society, vol. 20, no. 3, SAGE Publications, 2018, pp. 881–900, doi:10.1177/1461444816675438.

Li, Yachao, et al. “Communicating COVID-19 Information on TikTok: a Content Analysis of TikTok Videos from Official Accounts Featured in the COVID-19 Information Hub.” Health Education Research, vol. 36, no. 3, 2021, pp. 261–271., https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyab010.

Stanfill, Mel. “The Interface as Discourse: The Production of Norms through Web Design.” New Media & Society, vol. 17, no. 7, SAGE Publications, 2015, pp. 1059–74, doi:10.1177/1461444814520873.

“Thanks a billion.” TikTok Newsroom, 27 September 2021, https://newsroom.tiktok.com/en-gb/1-billion-people-on-tiktok-uk. Accessed 20 October 2021.

The ADHD doctor. https://www.tiktok.com/@thepsychdoctormd?lang=en. Accessed 18 October 2021.

“TikTok partners with educators to bring together short-form entertainment and learning.” TikTok Newsroom, 18 June 2020, https://newsroom.tiktok.com/en-gb/tiktok-partners-with-educators-to-bring-together-short-form-entertainment-and-learning. Accessed 20 October 2021.

“TikTok- Statistics & Facts.” Statistica Research Department, 5 May 2021, https://www.statista.com/topics/6077/tiktok/#dossierKeyfigures. Accessed 19 October 2021.

Thoensen, Bryan. “Investing to help our community #LearnOnTikTok.” TikTok Newsroom, 28 May 2020, https://newsroom.tiktok.com/en-us/investing-to-help-our-community-learn-on-tiktok. Accessed 19 October 2021.