Analysing the Twitch Data Leak: possibilities, limitations and requirements

Introduction

With the arrival of video game live streaming platforms, gaming has become a spectator form of entertainment. Live streaming lets players build an audience, brand, and income while streaming their game practices – often straight from their bedroom, turning the traditional consumer into content creators (Digital Surgeons 2015). Twitch is one of the biggest live-streaming platforms that host massive amounts of live video game content (Taylor 2018). The American video streaming service launched in 2011, blending in two distinct mediums: broadcast media and games. On Twitch, users can construct channels to stream their gameplay and competitions to the world. Thanks to the live comment section, interaction from viewers can take place in real-time. As of February 2020, Twitch has millions of users and a total of 3.8 million unique broadcasters, and it is the fourth-largest source of peak Internet traffic in the US (Delfino 2020).

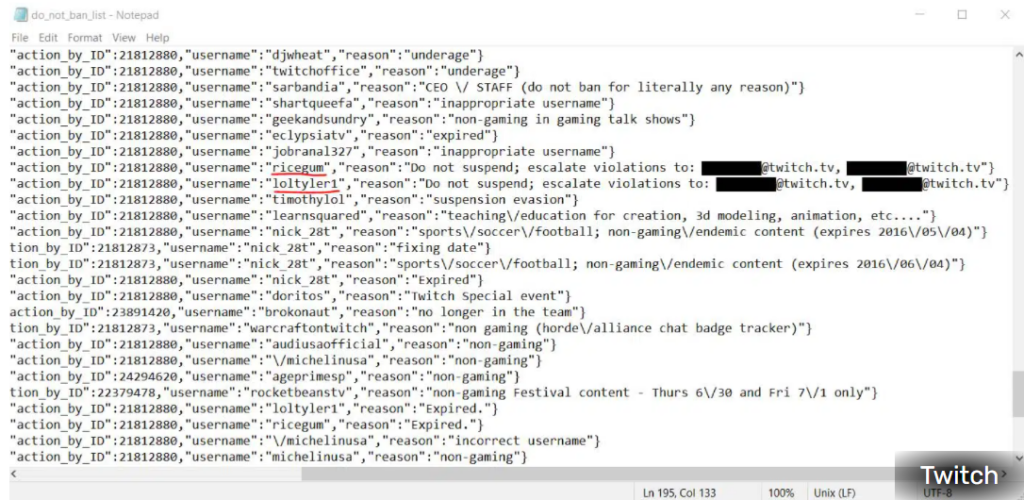

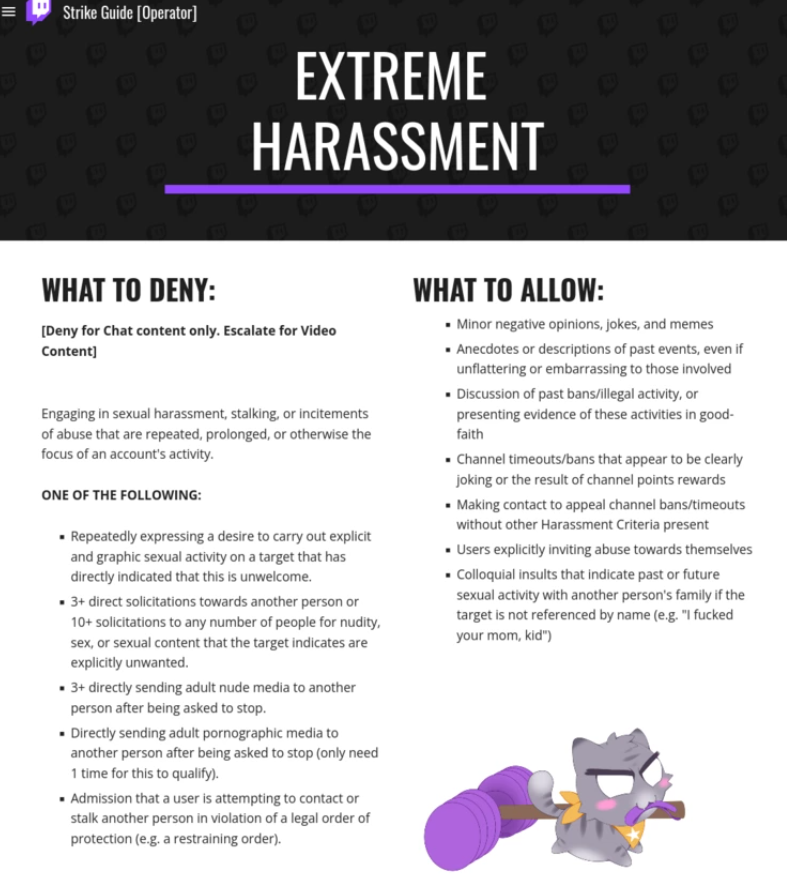

Twitch offers millions of broadcasters all kinds of opportunities to build online communities and transform their private play into public entertainment. However, underneath it all, technology companies are building and sustaining economic models that allow them to survive (Taylor 2018). On Wednesday, the 6th of October 2021, Twitch became the victim of a data leak, divulging confidential company information. More than 125GB of data leaked on 4Chan, including streamer pay-outs and moderation strike guidelines. (Tidy and Molloy 2021). News9 (2021) described the document as follows: “Twitch’s confidential guidelines for moderation includes pictures and examples of what content should be ‘denied,’ ‘allowed,’ or ‘escalated,’ giving distinctions and rules for what to leave and takedown.”. Another file in the leaked data is the “do_not_ban_list,” which caused a considerable controversy (Tidy and Molloy 2021). This list, filled with popular streamers, gives insight into the inner workings of Twitch, where it seems like certain streamers are given more leeway than others (Nightingale 2021).

Twitch is an exciting research topic because it is a relatively new yet unexplored medium (Sjöblom and Hamari 2017). Twitch has regularly been under fire from creators and users who feel like the site does not do enough to stop inappropriate content from being shared. The “do not ban list” leak resulted in even more controversy, with users feeling like high earning streamers are treated differently, implying that Twitch’s moderation practices are ruled by money and power. The debate related to Twitch’s moderation practices is not an isolated issue. Many social media platforms are facing problems related to moderation practices. Social media platforms are designed for engagement and, therefore, revenue. Nevertheless, unfortunately, the most engaging content is usually the most controversial (The Economist 2020).

Moderation is a widely studied topic, and it is essential to consider how moderation strategies shape the image of tech companies. Moderation guidelines are usually non-public documents, meaning users have minimal insight into platform content moderation operations (West 2018). This makes it hard for users to understand why certain users are banned or ‘de-platformed’ for breaking the rules and why others are not. This paper will analyze the Twitch data leak to explore if it constitutes a data point of great interest for research regarding the platform economy and governing practices, thus providing future researchers with enough information to warrant further investigations and highlighting possibilities, limitations, and requirements. We will conduct a content analysis of the leaked documents, including: (1) the internal moderation strike guidelines, (2) lists of the highest-earning streamers on the website, and (3) parts of the do_not_ban_list.

Theoretical Framework

Over the past years, online platforms’ moderation practices have garnered growing scholarly attention. From studies ranging from exploring how social media platforms police our online behaviour (Gillespie 2018) to the impact of moderation practices on marginalized groups (Sablosky 2021), the body of work on this subject is still growing.

As defined by Grimmelman (2015), moderation refers to “the governance mechanisms that structure participation in a community to facilitate cooperation and prevent abuse.” Today, most of us access the Internet through online platforms; being subjected to these mechanisms is no surprise. This moderation is an “essential, constitutional, definitional” practice for platforms (Gillespie 2018). Underlining the prominent role of moderation in the practices of online platforms, Gillespie (2018) even argues that platforms not only need moderation to survive, “they are not platforms without it.” Today, the platforms we use increasingly “determine what users can distribute and to whom, how they will connect users and broker their interactions, and what they will refuse.” (Gillespie 2018).

However, determining what is and is not allowed has proven to be a difficult task, as platforms have to consider a variety of stakeholders when formulating their rules and norms. Firstly, as most platforms operate globally, one has to consider that what is considered unacceptable in one country might be accepted in another. Besides that, one common characteristic of online platforms is that they serve multi-sided markets. Facilitating end-users and advertisers and sometimes other stakeholders, companies must keep all these different groups in mind when shaping their moderation protocols. As stated by Myers West (2018) when it came to the moderation practices of social media platforms: “although a social media company may have an interest in free expression that enables users to post as much content as possible, it may not desire the kinds of expression that scare away advertisers. Alternatively, it may seek to balance the need to maintain the perception of being an open platform with demands by governments to police certain kinds of content.”

The external influences described above play a part in shaping a platform’s moderation policies. As expressed by Gillespie: “Nearly all social media platforms are commercial enterprises, and must find a way to make a profit, reassure advertisers, and honor an international spectrum of laws.” This makes online platforms tread a fine line as they design their moderation mechanism, which becomes apparent when looking at the community guidelines of most of these platforms. The purpose of a platform’s community guideline is to provide users with an overview of the types of behavior and content that are allowed and disallowed. As found by Myers West (2018), however, most of these guidelines “tend to be fairly generic, to allow companies to navigate a core tension in their moderation of content.” This strategic lack of precision in the community guidelines leaves users with “limited insight into the evolving scope of platform content moderations” (Myers West 2018).

These unclear protocols have frequently been the cause of contention between platforms and end-users. The main reason for this is that users who are punished for acting against a platform’s policies are sometimes unaware of what they did wrong. Because of this, users often feel that they are being wrongfully or unfairly punished. With punitive measures ranging from content takedowns to temporary suspensions to being completely banned from a platform, these measures can substantially impact users (Myers West 2018, 4376). In her study of users’ experiences with content moderation on social media platforms, for instance, Myers West (2018) found that respondents acknowledged how these platforms provided them with the public good, granting them access to “support systems of communication that are deeply interwoven with social, political, and economic life.” (4376). The latter is especially the case for Twitch. As many users can garner income from their Twitch streams, being banned from the platform exceeds mere annoyance as it can have a tangible financial impact on them.

Considering the effects of platforms’ moderation policies on users – ranging from social to economic implications – it becomes clear why insight into the hidden moderation mechanisms is crucial. Users deserve to know the exact reason behind their punishment, and this allows reflecting and changing their behaviour to avoid being (repeatedly) penalized. As mentioned by Myers West (2018), besides the community guidelines designed for users, it has been found that platforms also have “non-public documentation that operationalizes the community guidelines at a much more granular level of detail” (4370). Through a study of these more detailed guidelines, one should be able to figure out what platforms expect from their users and draw conclusions as to why some things are allowed and some are not.

Methodology

The research conducted in this paper aims to explore if the twitch leaks constitute a data point of great interest for research regarding the platform economy and governing practices, thus providing future researchers with enough information to warrant further investigations in highlighting possibilities, limitations, and requirements. It does so by doing a content analysis of published documents, including the internal moderation strike guidelines for twitch operators determining how to handle behaviour and content produced by streamers on the website, lists of the highest-earning streamers on the website based on the payouts by Twitch regarding the number of subscribers and ad revenue, and parts of a do_not_ban_list. The content analysis angle is guided by contemporary literature from researchers on the platformization of the web, such as Gillespie and West, giving the investigation a firm stance in the scientific discourse and venturing beyond. In order to understand how the paper approaches the research concerning the twitch leaks, it is essential to understand the circumstances by which the data in this paper was obtained. All information, including screenshots and files used in the research, were made public across the web by journalists, news websites, and Twitch and remain visible as of publishing this paper. Non-journalistic sources or sources not directly related to Twitch in an official capacity posting illegally obtained data from the leak, for example, but not exclusively on social media platforms such as Reddit or the imageboard 4Chan were not used in the creation of this paper. This is due to a few apparent reasons:

- Legal Uncertainty: It is unclear to which extent the data made public in the wake of the breach is confidential and if engagement with the data through non-official Twitch or journalistic sources may be illegal on the national or international stage. Platforms other than Twitch quickly took down any data traces or sources included in the leak, warranting concern of possible repercussions.

- Technical Limitations:

2.1 The twitch leak is roughly 125 Gigabyte large, requiring a stable and high-speed internet connection to download all of the information without interruption. Since administrators of various sites are constantly taking down the download links to protect their operations from legal inquiries by Twitch. The remaining links are mostly magnet links allowing one to download the files via torrent; since the peer-to-peer torrent network relies on the internet speed of its contributors instead of large commercial servers, download speed and stability are further reduced.

2.2 The 125 Gigabyte of files are most likely compressed, thus requiring a machine powerful enough and extensive memory to assist in timely processing and saving of 125 Gigabyte that will at the very least double in size. Furthermore, once the data has been uncompressed, the files have to be indexed by the computer in a time-intensive process to be made searchable.

2.3 The data being searchable by the machine still requires the researcher to be computational literate and capable of understanding file formats, techniques of extraction, and processing to make good use of the search function to produce any valuable results. Despite the technical limitations and legal concerns, the data used in the following content analysis of the strike operator guidelines, the do_no_ban_list, and the streamer revenue chart can be regarded as genuine given the reputable sources they have been obtained from. Moreover, the relentless vigor by which hegemonic players of the platform economy are issuing takedown notices and banning digital traces of leaks reminds one of a whistleblower spelling state secrets, giving further credibility to the scope of possible future implications regarding the leaked data; therefore, a first glance at the surface may be obligatory.

Analysis

The Do Not Ban List

The first leaked document to be analyzed is the ‘Do Not Ban’ list. In 2016, this list first surfaced on social media platform Reddit. It includes the usernames of certain Twitch streamers. One of the names on the list, ‘Sarbandia,’ is followed by the statement: ‘(do not ban for literally any reason).’ It could be concluded that different rules apply to different users when it comes to banning. If the user Sarbandia breaches the guidelines established by Twitch, the account would not be banned from the platform, while other accounts would be banned in such cases. A double standard arises when multiple people are treated differently even though they should be treated the same way, which would be the case if Twitch does not apply the guidelines they have set to all their users.

The ‘Moderation Strike Guide’

The leaked document starts with information on ‘what to deny,’ ‘what to allow,’ ‘what to escalate,’ and ‘other hateful conduct violations.’ This is followed by examples and pictures to clarify the information and a list of hate symbols that are not allowed on the platform. An example of one of these hate symbols is the ‘White Power’ hand sign. As stated by Myers West (2018), platforms could not desire content that scares advertisers away. The symbol of White Power could be recognized as undesirable content, harming Twitch’s advertising revenue. In the leaked document, one could find more information on what is allowed on even more subjects such as adult nudity, porn or sexually explicit material, gambling referral and gore, and other obscene, obscene content. This corresponds with the statements of Gillespie (2018) about how platforms increasingly determine what users can distribute and what content the platform will refuse. This is shown in the Strike Guide by the lists of information on, for example, what to deny and allow.

The Payout List

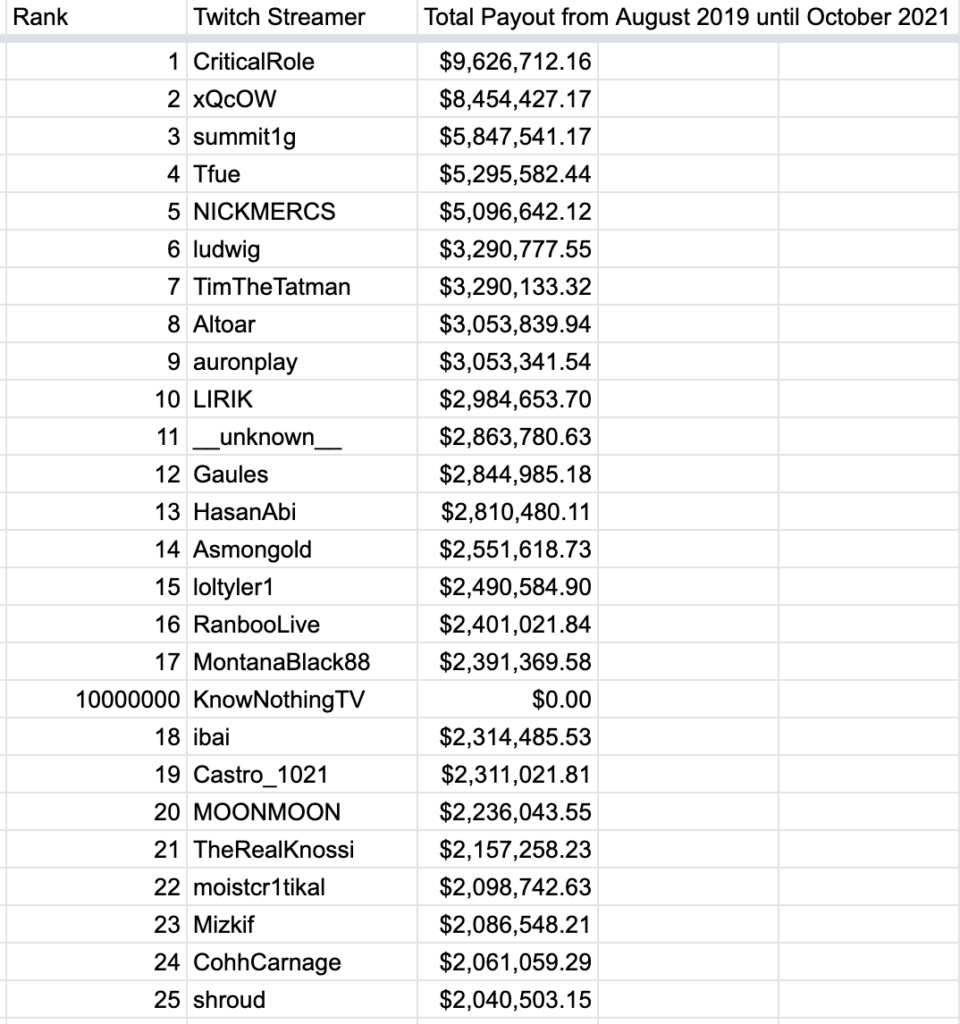

The last Twitch document that has been leaked is the list of the highest-paid Twitch streamers. The list shows the usernames of the streamers in a column on the left, and in the right column, one can see what they have earned according to the data from the data breach. These are the earnings since September 2019. First place on this list is held by a streamer called Critical Role, which has earned more than 9.6 million dollars. Following up on the second place is Canadian Twitch gamer xQc with 8.4 million dollars. It is important to note that the earnings on the list only include income directly paid by Twitch. Most popular streamers generate even more income through, for example, sponsorship deals or merchandise sales. An expression of Gillespie (2018) that has been included in the theoretical framework is how nearly all social media platforms are commercial enterprises wanting to profit. If the highest-paid Twitch streamers are banned from the platform because they breach the community guidelines, Twitch likely loses many of their users and, thus, income. This perspective could be a reason for Twitch’s double standard when it comes to banning users.

Conclusion

The leaked Twitch documents provide insight into the moderation practices of Twitch concerning their economic interests, exposing the dominant role of the platform. After analyzing the leaked documents, it could be stated that these documents and how Twitch handles their guidelines should be studied in more detail. First of all, the confidential nature of the ‘Strike Guide” raises questions about why exactly this guideline is hidden from users. As pointed out in our theoretical framework, making users aware of the exact reasoning behind their punishment can prove beneficial as it allows them to reflect on and learn from their mistakes, enabling them to prevent further repercussions or an eventual banning. The importance of this has also been underlined by Myers West, who stated that “if the overall objective of a content moderation system is to encourage better behavior on the part of users,” the system which obscures the reason behind the punitive measures fails, as it does not educate users and gives them “no opportunity for engagement with the platform to learn.” (Myers West 2018, 4379). Therefore, future research could investigate the exact motives behind Twitch’s confidential “Strike Guide.” Why do they feel that the users’ are better off without having access to these guidelines? Moreover, what are the contents that the platform is trying to hide from outsiders?

Secondly, the ‘Do Not Ban’ list raises the assumption that some users are treated differently than others. Further research in this subject could investigate whether certain sets of users are being treated more favorably than others and answer why this is the case.

Lastly, the relation between the ‘Do Not Ban’ list and the leaked payout list could also be questioned since there could be economic reasons not to ban specific users from the platform. One could test the statement that Twitch makes its moderation decisions based on commercial values.

Overall, possibilities for future research imply overcoming legal and technical limitations related to the Twitch data as described in the methodology, as well as commanding a certain extent of computational literacy as part of the (research-) effort to be able to conduct an informed and focused investigation of the leaks.

Bibliography

Delfino, Devon. 2020. ‘What Is Twitch? All You Need to Know About the Livestream Platform’. Business Insider, 11 June 2020. https://www.businessinsider.com/what-is-twitch?international=true&r=US&IR=T.

Digital Surgeons. 2015. ‘Twitch and YouTube Are Blurring the Lines between Consumers and Content Creators’’. Digital Surgeons, 18 August 2015. https://www.digitalsurgeons.com/thoughts/strategy/twitch-and-youtube-are-blurring-the-lines-between-consumers-and-content-creators/.

Gillespie, T. (2018). Custodians of the Internet: Platforms, content moderation, andthe hidden decisions that shape social media. Yale University Press. (1-23)

Grimmelmann J (2015) The virtues of moderation. Yale Journal of Law and Technology 17(42): 42–109.

Myers West, Sarah. “Censored, Suspended, Shadowbanned: User Interpretations of Content Moderation on Social Media Platforms.” New Media & Society 20, no. 11 (November 2018): 4366–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818773059.

News9. 2021. ‘Twitch’s Confidential Internal Strike Guide for Moderating Content Leaked’. NEWS9LIVE. 11 October 2021. https://www.news9live.com/technology/twitchs-confidential-internal-strike-guide-for-moderating-content-on-the-platform-leaks-125526.

Nightingale, Ed. 2021. ‘’Twitch “do not ban” list used to protect prominent streamers’’. Eurogamer (blog), 19 October 2021. https://www.eurogamer.net/articles/2021-10-19-twitch-do-not-ban-list-used-to-protect-prominent-streamers.

Roberts, Sarah T.. 2014. ‘’Behind the screen: the hidden digital labor of commercial content moderation’’. PhD Thesis, University of Illinois, Chicago, IL. https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/bitstream/handle/2142/50401/Sarah_Roberts.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Sablosky, Jeffrey. 2021. ‘“Dangerous Organizations: Facebook’s Content Moderation Decisions and Ethnic Visibility in Myanmar”’. Media, Culture & Society 43 (6): 1017–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443720987751.

Sjöblom, Max & Hamari, Juho. 2017. ‘’Why do people watch others play video games? An empirical study on the motivations of Twitch users’’. Computers in Human Behavior. 75. 985-996. 10.1016/j.chb.2016.10.019.

Taylor, T. L. 2018. Watch Me Play: Twitch and the Rise of Game Live Streaming. Princeton University Press.

The Economist. 2020. ‘Social Media’s Struggle with Self-Censorship’’. The Economist, 24 October 2020. https://www.economist.com/briefing/2020/10/22/social-medias-struggle-with-self-censorship.

Tidy, Joe and Molloy, David. 2021. ‘Twitch Confirms Massive Data Breach’. BBC News, 6 October 2021, sec. Technology. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-58817658.