New Media Art(ifically) Intelligent and Algorithmic? An Exploration into the Potential of the ‘New’ in AI and Algorithms as Producing Artworks

A submission by Goran Kusić, Jeanelle Grech and Marthe van de Graaff

Who doesn’t love an introduction?

The notion that machines can mimic features of human cognition has intrigued the new media art world in recent years. During the last half century, machine learning algorithms have progressed far enough that artificial neural networks can produce images that artists have written in computer programs in order to generate algorithmic art. According to Broeckmann (2016, 108) algorithms have found many different uses in art – they can generate images, shape human and machine interactions, and design objects.

Peters (2015, 28) polemicized that there is a technicality in mind and body, hence the humanities function as disciplines where culture is stored, interpreted and transmitted. According to him, in music, dance and poetry there is counting, and there is writing. From there one could posit that all art forms carry a technological quality which combines mind, body, space and technology http://mirziamov.ru/zaym-bez-otkaza. This research follows the line of thought where artistic creation is an amalgamation of the material, the technical, conceptual, physical and ideological. Therein lies the broad potential of algorithmic and AI creation, because it questions authenticity, agency, and our own beliefs of what creativity is, and how we can understand and/or develop it further. Miller (2020, chap.VI, para.1) proposes that when we program computers according to our understanding of creativity, that we cannot yet imagine a creativity that would belong to a computer that develops it without us. Herein lies our main question: How to treat the potentials that algorithms and AI provide in New Media art production?

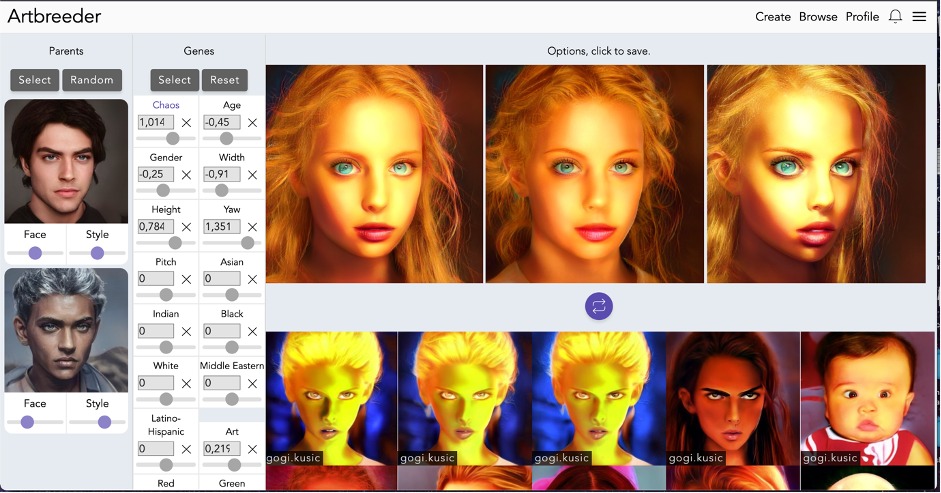

To answer the research question and respond to the emerging debates from the concepts proposed, a literature review is conducted together with a close reading of the attached artworks. An experiment is conducted at the end of the research project with the free tool Artbreeder, which allows for AI image manipulation across several categories.

An inquiry into AI and algorithmic art is interesting for media and other scholars alike. The interdisciplinary nature of the research and the many possible angles of examination make the field compelling, as well as challenging for inspection. In new media studies it opens debates on the use of data, the agency of technology, the potentials and pitfalls of artificial intelligence and algorithm use.

Some historical Context is even better…

Since the late 1950s, when a group of engineers at Max Bense’s laboratory at the University of Stuttgart began experimenting with computer graphics, artists have been employing computers to make artworks. Frieder Nake, Georg Nees, Manfred Mohr, Vera Molnár, and a slew of other artists experimented with the use of mainframe computers, plotters, and algorithms to create visually appealing artifacts (Garcia 2016). It is interesting to see how humans and machines are working together with art, which many consider to be a cultural practice that is linked to the human mind and skill rather than a machine. One of the earlier practitioners of this form is artist Harold Cohen, who wrote the program AARON in 1973 to produce drawings that followed a set of rules he had created. In describing the creation of AARON, Cohen wrote that the versions prior to 1980 worked with aspects of human cognition, making it possible for the program to understand similarities, positions, repetitive patters; he described it as a system for an expert, because it served as research tool to expand the researcher’s knowledge, instead of encapsulating the knowledge for others to use (ibid). Cohen continued to develop and refine AARON for the rest of his career, but the program maintained its core design of performing tasks as directed by the artist.

A theoretical Framework is especially lovable…

Big Data has been a compelling research topic across scholarly disciplines and its exacerbation as a crucial component of digital infrastructures has only furthered the polarizing debates concerning the concept. For the purpose of this paper, we look at Big Data as one of the necessary components in the creation of algorithmic and AI art. The working definition that is used as the lens for this paper follows Boyd and Crawford’s (2012, 663) division into three dimensions: (1)the technological – which looks at computation power and algorithmic accuracy to tackle large datasets for analysis; (2) the analysis dimension – which is relevant for identifying patterns in order to make overarching claims; (3) the mythology surrounding data – which proposes that through the use of big data insights and possibilities occur that offer new intelligence previously unattainable.

The strict focus of the research is not an analysis of Big Data and how it is used, but the interplay of these dimensions is vital to consider because they are intertwined with the creative processes that the paper’s examples treat. By considering the technological, analytical and mythological dimension, it is possible to further the understanding into algorithmic creativity and the particular ‘intelligence’ that the research questions.

Crawford (2021, 215) in her book directly addresses this ‘magical’ illusion of AI that is so commonly taken as fact; she criticizes the Cartesian dualism that is often employed in discourse on AI where they are seen as independent brains that produce knowledge completely independent from the structures in which they are deeply embedded. Every technology is embedded into its social, political and institutional context. That is why it is necessary to consider how in the process of creating new media artworks that these technologies have a deep connection to the artist, the data and environment in which they are contextualized.

There are sets of rules and functions that are put into the designs which are not alien or otherworldly, but very much material and not as intangible as they might come across. The interconnectedness of the processes involved in employing these technologies and the media that they produce is the space that the paper questions. As a site of experimentation, it can be argued that what such technologies do for artistic production is generate a different arena and expand possibilities. However, they do not do so completely on their own as they rely on infrastructures and datasets.

Peters (2015, 23) proposes that old media do not die, moreover, they are absorbed into what we call new, and are then reimagined. He further claims that all media raise enduring questions of life; the digital affordances of media have enabled services of collection and management for prayer, profit and power – which is both ancient, and modern(ibid).

These parallels are a guideline through the research process. It is far beyond the scope of this research to argue within art what is indeed new, and what is reimagined, as many art and history scholars have written extensively on such debates. However, what is relevant for this paper is situating the case studies, reflecting upon what the new-ness of algorithms and AI in art can be indicative of, when considering new media artistic production.

Media scholar, theorist and philosopher Marshall McLuhan in his book ‘Understanding Media’ has elegantly combined the how media, technology and art are intertwined:

No society has ever known enough about its actions to have developed immunity to its new extensions or technologies. Today we have begun to sense that art may be able to provide such immunity. In the history of human culture there is no example of a conscious adjustment of the various factors of personal and social life to new exceptions except in the puny and peripheral efforts of artists. The artist picks up the message of cultural and technological challenge decades before its transitioning impact occurs. He, then, builds models or Noah’s arks for facing the change that is at hand.(McLuhan 1994, 71)

Pasquinelli and Joler (2020) in their mapping of AI attempt to secularize it into an understanding of how it functions as an instrument of knowledge, and not as an ‘intelligence’. Such treatment directly tackles the mythological tendencies around algorithms and AI because it gives it a more concrete theoretical grounding, where one can actively avoid ascribing legend-alike cognitive capabilities. Rather, it gives materiality and technological affordances a place where they are an extension of creation, not a mind of its own, free of any human intervention.

Where they are especially critical is in their claim that AI – like many forms of automation – functions as a map of approximations and potential outcomes; however, still unavailable for community consent and access(ibid). In the area of new media algorithmic and AI art, one can see that access is indeed a crucial component into what can and cannot be appropriated for creative production. Yet it can then also be posited that exactly new media art can offer potential interventions into access to AI for artistic production. Digital media art co-created by algorithms and AI fills this gap, because it relates the producer, tool, data and consumer together in an almost circular relation to one another.

Examples are the cherry on top…

PATTERNS

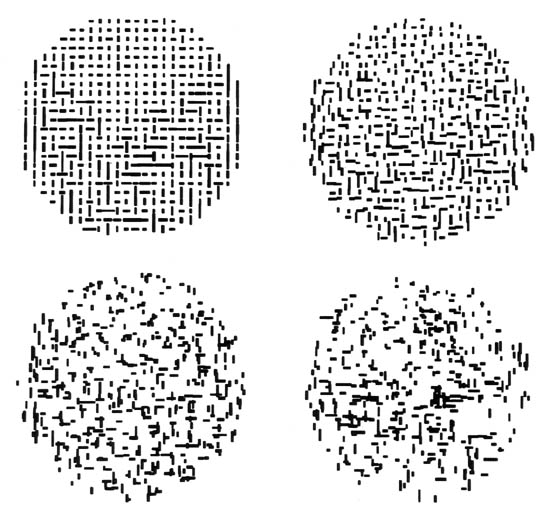

Early noticeable examples of AI and art were made by engineer A. Michael Noll in 1962, who experimented with an IBM machine’s creativity by having it make random patterns. Later, this would be called ‘computer art’ by fellow programmers and cultural historians (Pepi, 2020). Noll however, decided the results should simply be called ‘patterns’. Arthur I Miller (2020) wrote about these ‘patterns’, comparing the AI used to the human brain, arguing that the production of new knowledge from already existing knowledge is what happens to both. This is an example of minimal human interference, where the result is still deemed artistic. However, this notion could also be the result of the time it was discovered, with it being new and relatively aesthetically pleasing. It also falls neatly in line with Pasquinelli and Joler, because in spite of minimal human intervention, the machine is an extension, a tool to produce these patterns of material creation.

Figure 1 Michael Noll’s patterns ‘A. Michael NOLL at the Digital Art Museum’. n.d. Accessed 25 October 2021. https://dam.org/archive/noll/artworks_04.htm.

Figure 2 Michael Noll’s ‘Gaussian-Quadratic’ ‘History of Information’. n.d. Accessed 27 October 2021. https://historyofinformation.com/image.php?id=4737.

AICAN

Art made by AICAN differs greatly from Noll’s work in the way that this system was specifically designed to autonomously make art. It also differs in that it generates art based on other artworks and existing art genres, opposed to the ‘new’ art style of ‘patterns’. It builds off of something that already exists. The controversial issue is here, that if the system generates something novel, engaging or moving, it is hard to decide who is credited for it. What is also interesting, is that an experiment proved many people could not tell the difference between AICAN and human art. This proposes questions about the importance of authenticity and puts a lot of weight on the human perception of art. Crawford’s framework neatly complements the questions surrounding these works: there are no magical dimensions, but an interconnection of human created art and AICAN.

Figure 3 AICAN artworks Elgammal, Ahmed. n.d. ‘Meet AICAN, a Machine That Operates as an Autonomous Artist’. The Conversation. Accessed 17 October 2021. http://theconversation.com/meet-aican-a-machine-that-operates-as-an-autonomous-artist-104381.

GAN

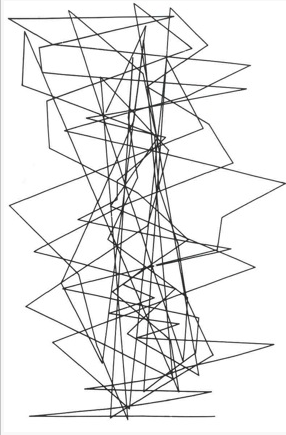

Another example is the work of artist Casey Reas. The main difference between this and AICAN’s artwork, is the many steps involved in the production of art made by the GAN system. Artists who work with GAN need to select and upload a large set of images. Then, the artist must interfere with the system to get a desired outcome, by deleting and adding certain pictures. However, the artist never has full control as the result is always a matter of testing and learning, as nobody is entirely sure how the systems’ layers learn. Whilst the process is therefore machine influenced, Reas argues that each of these steps can be compared to the steps any ‘normal’ artist takes when working.

Choosing equipment and materials, making changes to get a desired result, and leaving the last bit up to the tool. With the use of AICAN, many artworks have been made that imitate specific genres or even artists (Pepi 2020). What is interesting about this type of art, is that it once again leaves us to think about the way we not only view, but critique art. When critiquing the artist, the main point must be in consideration to the selection process of the artist. This puts more weight on the process of the art, rather than the artwork itself. Peters’ treatment of the old subsuming into the ‘new’ and questioning what about such an artwork is in fact novel are demonstrated in the example of the Mona Lisa reimagined in different styles.

Figure 4 Variations of ‘Mona Lisa’ Pepi, Mike. 2020. ‘How Does a Human Critique Art Made by AI?’ ARTnews.Com(blog). 6 May 2020. https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/features/creative-ai-art-criticism-1202686003/

THE NEXT REMBRANDT

The Next Rembrandt is a project that was initiated by ING Bank and company Walter Thompson, where they worked together with Microsoft to bring the work of the artist Rembrandt van Rijn back to life, almost four hundred years after his death. This project is very different from the previously discussed AICAN artworks, because there is a large team involved. Data scientists, AI developers AI and 3D printing experts worked on the project for 18 months. In this time, more than 160 thousand fragments were scanned from 346 paintings and processed with a deep learning algorithm. Even his brushstrokes were replicated by using depth scanning and 3D printing brushstrokes (Schlackman 2020). In terms of the paper’s questions on AI art, this project opens a lot of debates. For example, the final product is not an individually desired result from an artist, but the result of technical experts and machine learning. Many people were involved in the process, yet it seems as if the result is mostly machine generated, with every final ‘decision’ being made on the basis of existing work and carefully acquired data – which again proposes questions of authorship, and new-ness.

Peters’ argument would then propose that AI and algorithmic art stand at a similar frontier of new and old, as does the much-contested debate on what media is indeed ‘new’ and what makes it such. Boyd and Crawford’s three dimensions of data are also particularly relevant here as they are deeply embedded in this work: an extensive technological and analytical part took place, to create an almost mythological ‘new’ or ’next’ Rembrandt.

Figure 5 ‘The Next Rembrandt’ Schlackman, Steve. “Who Holds The Copyright in AI Created Art.” Art Business Journal. September 29th, 2020. https://abj.artrepreneur.com/the-next-rembrandt-who-holds-the-copyright-in-computer-generated-art/

MODERN DAY USE OF AI

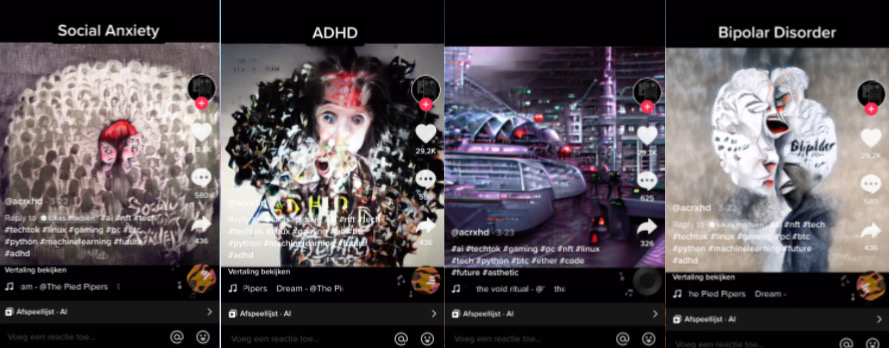

The Next Rembrandt is a fascinating example of using highly capable technology by experts to re-work a text. Yet other, more accessible forms of AI creation are showing up in online spaces. An example of this is seen on TikTok, where multiple users entertain large quantities of viewers by generating requested AI images. For example, the creator makes an AI system generate visual images based on certain words or questions. The results have evoked all kinds of reactions from viewers. This is partially due to the themes of the AI visuals, like mental illness and many controversial topics like death, life, emotions, etcetera.

This shows how integrated AI can be in everyday life, but also how thin the line is when discussing AI and art. Following McLuhan’s train of thought, here the artist re-creates messages of the cultural and technological. The impact is difficult to discuss or map, which also falls in line with his argument that the models for changing perception might be ahead of their time. If art is defined by being authentic, moving, or even valued by perception, simple generated visuals like this can in spite of their simplicity when compared to large-scale projects like The Next Rembrandt, are indeed new media artworks. It can be argued that in the Tik Tok example, Pasquinelli and Joler’s call for intervention is precisely what’s happening. Community interaction with technology to create algorithmic art, at a very low barrier of access.

Figure 6 Screenshots of User @acrxhd. Posts with AI generated viuals. TikTok. Accessed October 27th, 2021.https://vm.tiktok.com/ZM8antDqJ/

We all experiment a little…

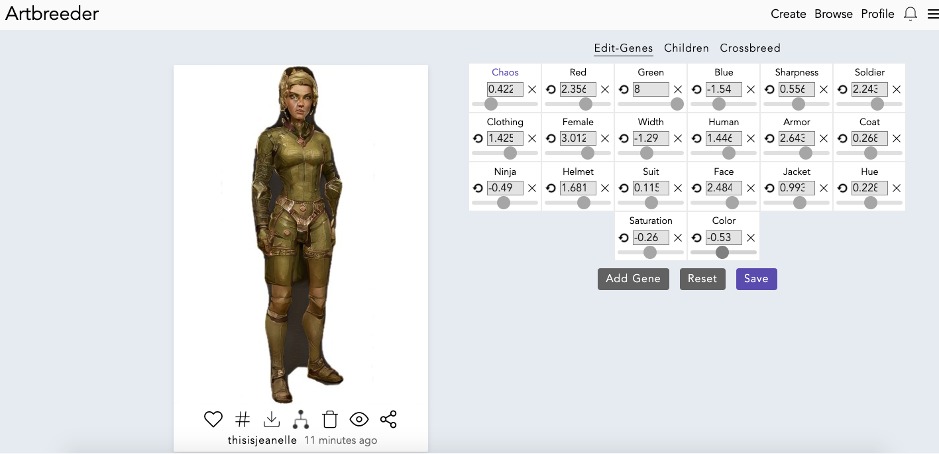

ArtBreeder

An example of a Generative Adversarial Network, is the website Artbreeder. It uses BigGAN and StyleGAN models, and strives to be a new type of creative tool that encourages people to cooperate and explore their ideas. Initially known as Ganbreeder, it began as a test to breed and collaborate techniques of exploration in high-complexity areas of AI. This experimental website allows the use of machine learning with image combination, and permits users to create different types of images to their own personal customization. The range of image types varies from portraits, landscapes, buildings, painting, sci-bio art, characters, albums, furries and anime portraits. With a free account one can pick from the options mentioned and, slightly change the settings that the tool offers and create an image based on the inputs the user decides upon.

Artbreeder is becoming a popular tool for people to incorporate AI to make art and visuals. It can act as a site of intervention for AI creation as it has a low barrier of entry and offers various options. The possibilities of Artbreeder are endless and the results are diverse, creative and often times aesthetically pleasing and even emotion-evoking. This proposes a lot of questions within the proposed debates. A relatively new and obscure artform like AI art, is suddenly becoming ‘common’. This questions how we define art and how art and how we critique it. It makes us think about how we can define art and the importance of the process versus the result. Other projects included in the research were funded differently, did not offer much open access in the process and are connected to institutions. Tools such as this one has the potential to make AI and new media art even more participatory as its digital aesthetic has a certain kind of ‘known’ feel to it. Lastly, it questions the reimagination of art as a specific style and how we position it within the more classical and longer existing forms of art.

Figure 7 Screenshot from a created character that was built with the tool by Jeanelle Grech

Figure 8 Screenshot from an exploration of a portrait creation by Goran Kusić

And for the grand finale…

The chosen examples and experimented artworks have shown the sheer versatility and potential of using algorithms, datasets and artificial intelligence for artistic production. The debates presented in the paper concerning new-ness, authorship and technological agency do not have any one absolute response. Moreover, the deeper one delves into exploration of AI and algorithms in new media art, the more questions arise and additional layers provide additional challenges. However, there is a certainty: the potential of creative expansion is practically limitless. What needs to be taken into consideration are the dimensions of technological materiality and their embeddedness into their contexts. To see AI and algorithms as possible extensions of creativity as co-producers, is a starting point for further examination of the creative potentials and theoretical and practical conundrums concerning their use. With special attention to where and how the AI and algorithms are employed in new media art production; their practically limitless potentials can be treated as the next frontier in digital creativity.

Nobody ever reads this, but you really should, the sources are great!

boyd, danah, and Kate Crawford. 2012. ‘Critical Questions for Big Data’. Information, Communication & Society 15 (5): 662–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.678878.

Broeckmann, Andreas. 2016. Machine Art in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England: The MIT Press.

Crawford, Kate. 2021. Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Elgammal, Ahmed. “Meet AICAN, a Machine That Operates as an Autonomous Artist.” The Conversation. October 17th, 2018. https://theconversation.com/meet-aican-a-machine-that-operates-as-an-autonomous-artist-104381.

Garcia, Chris ‘Harold Cohen and AARON—A 40-Year Collaboration’. 2016. CHM. 23 August 2016. https://computerhistory.org/blog/harold-cohen-and-aaron-a-40-year-collaboration/.

Jochim, Beth ‘A Short Overview on AI Art’. 2021. Libre AI. 24 May 2021. https://www.libreai.com/a-short-overview-on-ai-art/.

McLuhan, Marshall. 1994. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press.

Miller, Arthur I. 2020. The Artist in the Machine: The World of AI-Powered Creativity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.Apple Books.

Pepi, Mike. 2020. ‘How Does a Human Critique Art Made by AI?’ ARTnews.Com (blog). 6 May 2020. https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/features/creative-ai-art-criticism-1202686003/.

Peters, John Durham. 2015. The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media. 1st edition. Chicago ; London: University of Chicago Press.

Schlackman, Steve. “Who Holds The Copyright in AI Created Art.” Art Business Journal. September 29th, 2020. https://abj.artrepreneur.com/the-next-rembrandt-who-holds-the-copyright-in-computer-generated-art/.

‘Scrying Pen by Andy Matuschak – Experiments with Google’. n.d. Accessed 28 October 2021. https://experiments.withgoogle.com/scrying-pen.

Simon, Joel ‘Artbreeder’. n.d. Accessed 27 October 2021. https://artbreeder.com.

‘The Nooscope Manifested: AI as Instrument of Knowledge Extractivism’. n.d. The Nooscope Manifested: AI as Instrument of Knowledge Extractivism. Accessed 24 October 2021. http://nooscope.ai/.

User @acrxhd. Posts with AI generated viuals. TikTok. Accessed October 27th, 2021. https://vm.tiktok.com/ZM8antDqJ/