True Crime TikTok: Affording Criminal Investigation and Media Visibility in the Gabby Petito Case

By: Gabrielle Aguilar, Sofia Ompolasvili, Luisa Garcia Amaya, and Sophie Kerstens

On July 2, 2021, micro-influencer Gabby Petito set out on a cross-country road trip across the United States with her fiancé Brian Laundrie. Along the way, Petito hoped to grow her social media following by sharing the #vanlife with her friends, family, and personal audience. One YouTube video, two months, and seventeen Instagram posts later, Petito was reported missing, and “Find Gabby Petito” secured itself a space in the conversations of our media-saturated, information-rich world. Petito’s disappearance sparked global interest in large part due to viral videos shared on the TikTok platform by websleuths that leveraged traces of Petito’s existing online presence to make inferences on her whereabouts and the conditions of her disappearance. This commentary will offer a critical look at the Gabby Petito investigation by specifically drawing upon video content from four prominent TikTok content creators who had a significant online presence vis-à-vis the Gabby Petito investigation. Though the amount of content on the case far exceeded that of these users, this assemblage will allow us to have a concise overview of key findings and to position criminal investigation, by way of true crime TikTok, as an affordance of the TikTok platform. An affordance refers to the range of functions and constraints that an object provides for, and places upon, structurally situated subjects (Davis & Chouinard 2017). In doing so, we will highlight the concept of media traceability and visibility as key factors that contributed to the widespread theories and speculations around the case. The selected users for this commentary include websleuths Haley Toumaian and Paris Campbell as well as users Miranda Baker and Jessica Shultz who shared evidence on the case publicly through their TikTok profiles.

Mapping Digital Traces on True Crime TikTok

On September 13, 2021, two days after Gabby Petito’s family reported her missing, comedian and self-proclaimed storyteller Paris Campbell took to TikTok to share her thoughts on how ‘sus’ (read ‘suspicious’) the circumstances of the Petito case were. The video would go viral on the platform, spark a global conversation on the investigation, and fuel masses of true crime fans and content creators to come together. Paris Campbell had suddenly become a comedian, storyteller, and websleuth. Websleuthing is understood as users “[engaging] in varying levels of amateur detective work including but not limited to searching for information, uploading documents, images, and videos, theorising, analysing, identifying suspects and attempting to engage with law enforcement and other organisations and individuals connected to the cases” (Yardley et al. 2016, 2). Hashtags like #findgabbypetito and #gabbypetitotheory became flooded with videos on TikTok by users who began to investigate Petito and Laundrie’s digital traces and share their findings and opinions with the public.

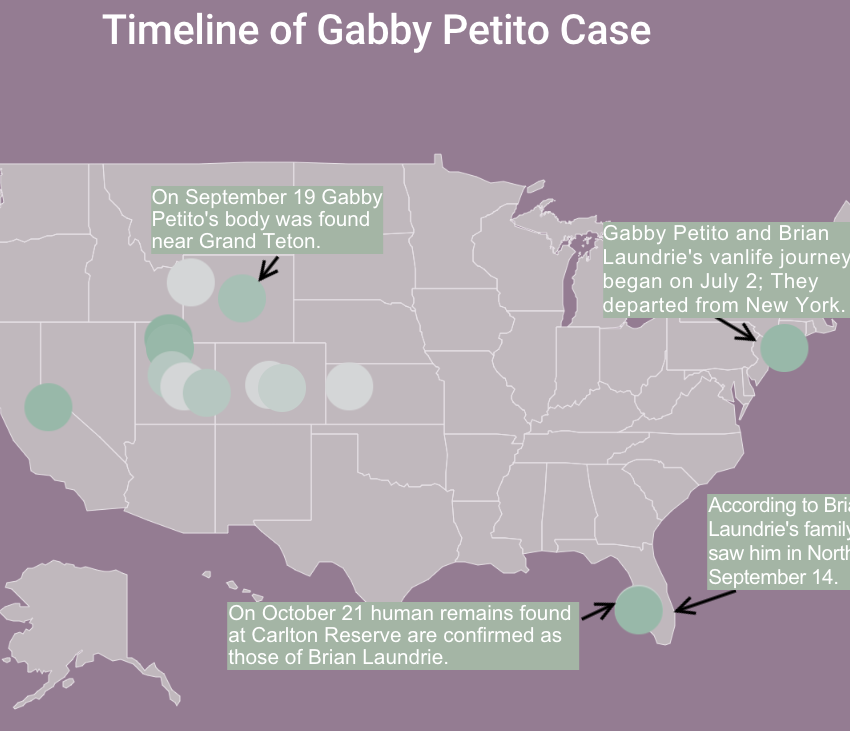

“A digital trace is any inscription produced by a digital medium in its mediation of collective actions – for instance, a post published on a blog [or] a hyperlink connecting two websites…” (Venturini et al. 2018). The idea of media traceability assumes that online activity can be analysed to critically make inferences based on patterns and highlights a new affordance of digital media in processing and analysing data. Using digital traces, TikTokers and legal authorities began separately, but simultaneously, mapping out the couple’s geolocation and deducing where Petito may be found. While legal authorities made use of an open source intelligence tool called EPIEOS, websleuths used geotags from the couple’s Instagram posts, information from AllTrails (a fitness and travel mobile app used for outdoor recreational activities), their one YouTube video, and even investigated their Spotify listening habits and Pinterest account activity.

This map we created demonstrates all the key locations tracked to identify a timeline of the couple’s movement across the country. The indicated points were traced from the Instagram posts uploaded by Petito on her page and information shared by her family members, TikToker Miranda Baker, and legal authorities.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Media Visibility Afforded by True Crime TikTok

Digital vigilantism describes individuals engaging in the use of technologies to assist in new forms of criminal justice (Trottier 2017) and highlights the complicated relations of visibility and control between the public and the police. The media’s fixation with Petito’s disappearance has sparked an ongoing debate regarding how online creators, particularly those who specialize in true crime, have contributed to such investigations– is their time and effort helpful or does it take away from the case? Todd G. Shipley, President of the High Technology Crime Investigation Association (HTCIA), noted that “the input from social media users can be beneficial for an investigation because these users have the time to comb through online data that law enforcement might not.”

Users may also establish a foundation, collect funds, and expand the amount of resources or man-power that goes towards an investigation (Reilly 2021). The increasingly participatory ethos of the web (Gillespie 2014) also highlights the often communal aspect of true crime media– once a discourse in which a user participates goes viral, those users tend to feel like they are a direct part of it (Slakoff 2021). In the 20 days that followed the Petito missing persons report, as new details and speculations continued to unravel in the public eye, Petito’s Instagram following was also growing by over 700,000 as strangers hoped for her to be safely found.

Jordan Wildon, a digital investigator who follows online misinformation and disinformation, posted on Twitter that “posting every little detail” of a case without verification can be counterproductive, and in some cases, harmful to an investigation (Wildon 2021). Law enforcement hotlines also reported an overflow of calls from ‘case followers’ who claimed to have seen Petito or have unique information related to her case, but many repeated the same information (Cains 2021). This redundancy of information, part of which entail unsubstantiated speculations, contribute to a general “noise” that causes law enforcement to use, or even waste, resources vetting through.

Additionally, conjecture and criticism have arisen around people that have capitalised on Petito’s situation to increase their own social media popularity or that have gone as far as to harass the individuals/families involved in the case. Amid the TikTok community pointing their fingers at Brian Laundrie for the disappearance of Petito, despite having not been charged with any crime beyond fraudulent use of her credit card, Laundrie too was reported missing on September 17, 2021.

White Woman Syndrome and Virality on True Crime TikTok

While true crime TikTok has enabled masses of individuals to contribute to an investigation, there is a concern as to why Petito’s case went viral and tractioned so much visibility when many other cases do not. Virality has been characterised as fast-moving information flows that reach many people and happen as a result of sharing (Nahon & Hemsley 2013). According to criminologists and academics, the Petito case clearly illustrates a lot about what causes some missing person cases to gain widespread attention and ‘go viral’ while other cases/investigations remain relatively unknown. They explain that Petito’s race and age contributed to the public’s increased interest in her disappearance– alluding to what has been described as ‘missing white woman syndrome,’ a term coined by social scientists and media commentators to describe the media coverage of missing-person cases involving young, white, upper-middle-class women or girls, particularly on television, as opposed to the alleged lack of attention paid to missing women who are not white, women from lower social classes, and missing men or boys (Sommers 2016).

A recent report published on Missing and Murdered Indigenous People in Wyoming (where Petito’s was last seen) reinforces this media ‘syndrome’ by highlighting that only 30% of indigenous homicide victims’ cases get covered by newspaper media outlets compared to 51% of White homicide victims (Grant et al. 2021). Another report also shows missing persons cases dating back to 1958 where the individuals went missing while also visiting national parks as Petito and Laundrie were. The Petito investigation’s nonstop media coverage, within traditional media and also within social media platforms, has been hurtful to relatives of non-White and LGBTQ individuals who haven’t received the same intensive media coverage as Petito. With global attention and increasing resources going towards the investigation, the concerted search for Petito uncovered at least nine individuals, many of which were people of color, and placed a spotlight on the huge disparity between media coverage and police efforts involving missing people of color. The search for Laundrie also led to the discovery of other missing people of color. Petito’s remains were eventually found and identified on September 21, 2021, and the case transitioned from ‘missing’ to ‘murder’ while Laundrie remained missing.

Petito was not only an example of a ‘Missing White Woman’ exploited by news media outlets, but she also had a micro-following on Instagram. As a result, individuals felt more linked to Petito. As this online community grew, more knowledge was obtained by the devout following, and content creators also felt attached to their efforts to bring her justice. Chun (2016), further explains how, face culture’s socialisation goals can thus be seen as one of habituation, training users to feel an indivisible connection with their datafied selves, “so that a relatively solid longitudinal data set, which follows individuals and individual actions through time, can emerge” (Chun 2016, 57). According to de Zeeuw and Tuters, this phenomenon occurs because the dominant face culture of social media platforms strives to align and continuously link offline and online actions and identities as part of a single personal profile and corresponding data double (2020). Face culture first emerged in the mid-2000s on mainstream surface online platforms. As we currently can observe on platforms like Instagram and TikTok, which can clearly demonstrate how Gabby Petito became a prime example of face culture.

Patterns across the #gabbypetito TikTok timeline

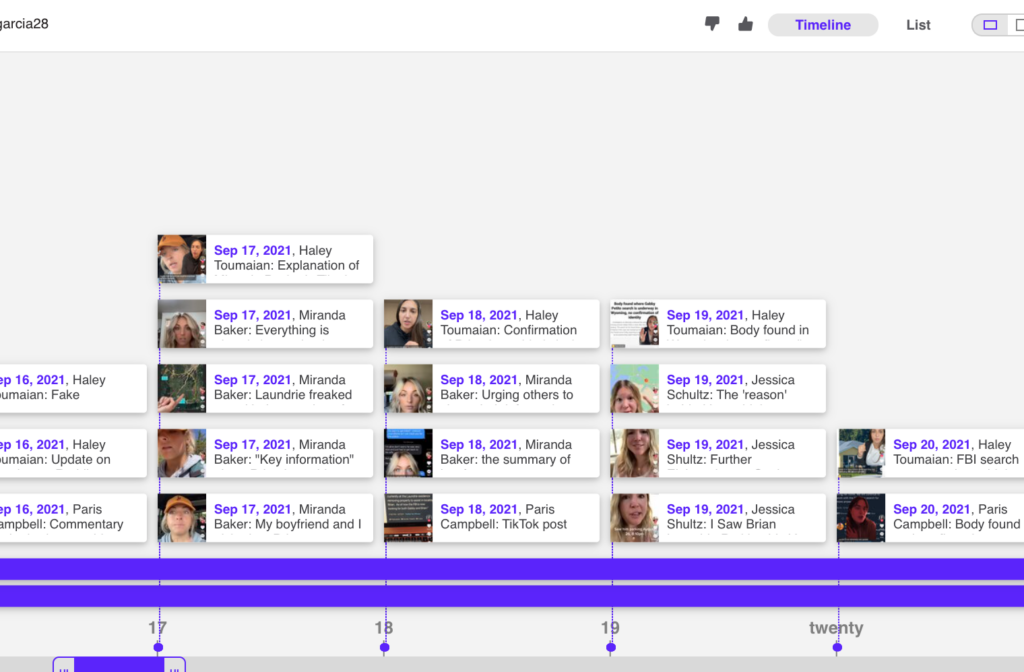

“While it is agreed that viral videos may bear considerable political impact, many questions remain about their sources, content, and diffusion patterns” (Shifman 2014, 124). To complement this paper we assembled a visual timeline on TimeToast, a web-based tool for creating interactive timelines, to highlight video posts from the four selected TikTok creator’s who actively spoke about Gabby Petito’s disappearance and eventual discovery online. Enmeshed with the Petito investigation, these creators also shared online content investigating the disappearance and discovery timespan of Brian Laundrie, which is also visualised in our timeline. The timeline begins with Paris Cambell’s first viral video on the case on September 13, 2021 and ranges up to October 23, 2021 when the death of Brian Laundrie had been confirmed by the press.

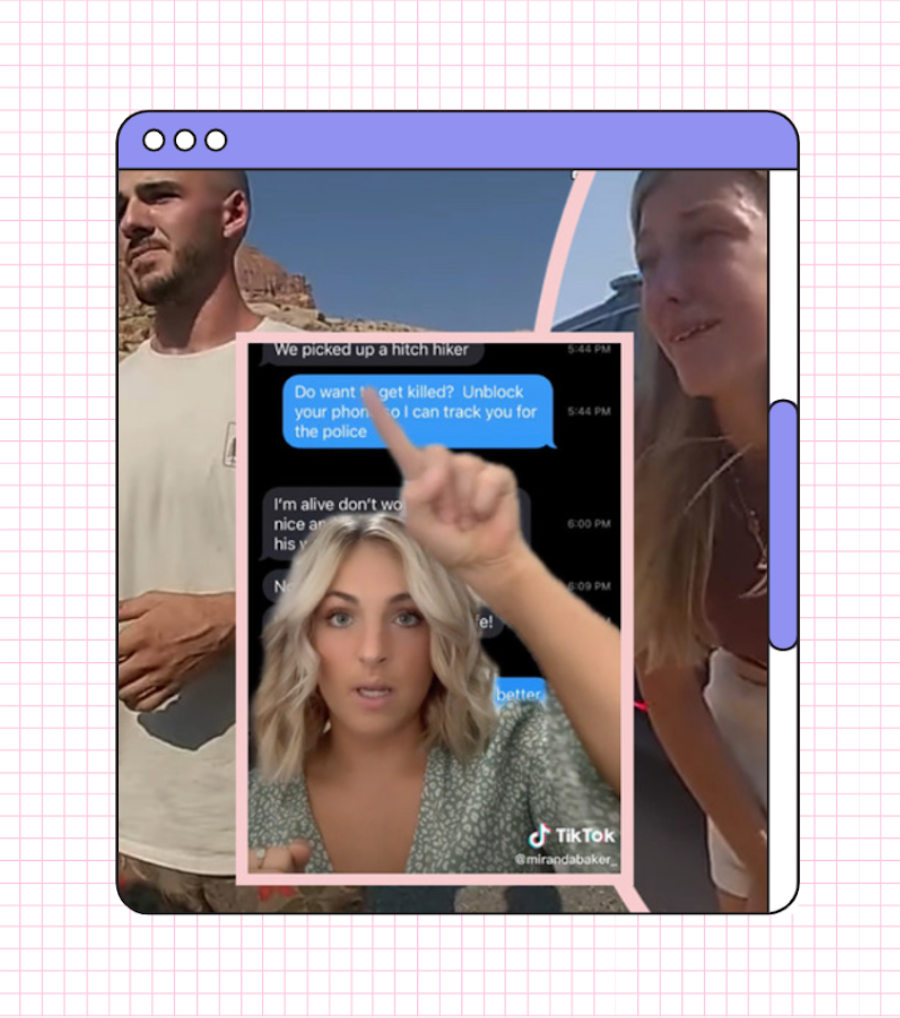

One of the most visible patterns in the timeline we identified was the difference between posts that were uploaded by those who publicly shared key pieces of evidence and those who tried to investigate and contribute their findings to the Petito case investigation. Miranda Baker and Jessica Shultz, for example, came forward with first-hand evidence which they primarily shared with the legal authorities but chose to publicise in a series of videos uploaded under the hashtag #gabbypetito on TikTok. Their evidence ranged from maps, dates, and locations to sharing screenshots of private messages with their relatives or investigators to show their cooperation with the investigation. While it was speculated that they took to TikTok for clout, they note that the aim of these posts was to spread information among the platform’s users and possibly urge those who have any further information that may help the search, to share it with those in charge of the investigation.

On the other hand, users like Haley Toumaian and Paris Campbell who did not have first-hand evidence related to the case were much more staunch in their commitment to websleuthing practices. Toumaian and Campbell contributed a wide variety of speculations and theories in addition to investigating data that had not yet been acquired by official investigators, getting information from authorities, attempting to reach out to the family, and reposting it.

Adopting a sort of ethical framework, Toumaian opted to disclose in her post captions that her videos contain unconfirmed facts as an attempt to avoid spreading further misinformation. In addition, Toumaian has almost exclusively shared content on her account related to the Petito investigation and has not shared content on other subjects/topics. Toumaian’s goal of fighting misinformation and false information has been seen to a great extent through videos where she responds to, and interacts with, unfounded comments and claims on her posts. While creators like Paris Campbell, conversely, shared content in abundance– updates with confirmed and unconfirmed information as well as content on other topics and subjects of investigations. After the critique of “White Woman Syndrome” that resurfaced on the TikTok platform amid the Petito case, Campbell also began to share investigative posts on missing person reports for individuals of color.

Conclusion

As indicated by Kitchin in The Data Revolution (2014), “data are never simply just data; how data are conceived and used varies between those who analyze and draw conclusions from them”(4). As a response to the critical reflection on the promises and perils of websleuthing, the recent formation of the True Crime TikTok community in the case of the Gabby Petito and Brian Laundrie investigation has demonstrated criminal investigation as an affordance of the platform. Data in these investigations play a crucial role in the production of power and knowledge that can transcend online/offline distinctions while complicating relations of visibility and control between the police and the public (Trottier 2017).

As websleuths collected data from the couple’s media traces, shared their own videos with confirmed and unconfirmed information and speculations, their videos, in turn, acted as their own media traces for other true crime TikTokers to draw conclusions. What emerged was a complex assemblage (Paasonen et al. 2015) that gave rise to a contingent network of websleuths. The production of content by said websleuths exhibited the power to draw the attention of the general public and invite them to collectively uncover the story. Media traceability, and the abundance of digital traces from Petito and Laundrie, played a key role in empowering individuals to mimic the highly-skilled role of a criminal investigator in an informal way on TikTok. While there is ethical concern with the potential for misinformation to go viral and exhibit a power that could shape future investigations, it is important to note that this affordance not only enabled the creation of a new reality but was also shaped by a reality of its own.

Bibliography

Cains, G. 2021.”Gabby Petito and the Obsession with True Crime.” The Scarlet. October 1, 2021.

https://thescarlet.org/17630/opinions/gabby-petito-and-the-obsession-with-true-crime/

Chun, W. H. K. 2016. Updating to Remain the Same: Habitual New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Davis, J.L., & Chouinard, J.B. 2016. “Theorizing Affordances: From Request to Refuse.” Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 36, 241-248.

de Zeeuw, D., & Tuters, M. 2020. “Teh Internet Is Serious Business: on the Deep Vernacular Web and Its Discontents.” Cultural Politics 16 (2): 214–32.

Gillespie, T. 2014. “The Relevance of Algorithms”. In: Gillespie, T, Boczkowski, P J and Foot, K A (eds.) Media Technologies: Essays on Communication, Materiality, and Society. Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 167-194.

Grant, E., Dechert, L., Wimbish, L. & Blackwood, A. 2021. “Missing and Murdered Indigenous People.” Laramie, WY: Wyoming Survey and Analysis Center.

https://wysac.uwyo.edu/wysac/reports/View/7713

Kitchin, R. 2014. “The data revolution : big data, open data, data infrastructures & their consequences.” Los Angeles, California: SAGE Publications.

Nahon, K., & Hemsley, J. 2013. Going viral. Cambridge, England: Polity Press.

Paasonen, S., Hillis, K., & Petit, M. 2015. “Networks of Transmission: Intensity, Sensation, Value”.In Hillis, K., Paasonen, S., Petit, M. (Eds.), Networked affect (pp. 1–24). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Reilly, P. 2021. “Gabby Petito Foundation Raises over $13k in First Fundraiser on Long Island.” New York Post. October 18, 2021.

https://nypost.com/2021/10/18/gabby-petito-update-foundation-raises-over-13k-in-first-fundraiser-on-long-island/

Shifman, L. 2014. “May the Excessive Force be With You: Memes as Political Participation.” In Memes in Digital Culture. The MIT Press. DOI:10.7551/mitpress/9429.003.0010

Slakoff, D.C. 2021. “The Mediated Portrayal of Intimate Partner Violence in True Crime Podcasts: Strangulation, Isolation, Threats of Violence, and Coercive Control.” Violence Against Women.

DOI:10.1177/10778012211019055.

Sommers, Z. 2016. “Missing White Woman Syndrome: An Empirical Analysis of Race and Gender Disparities in Online News Coverage of Missing Persons.” The Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology, 106(2), 275–314.

Trottier, D. 2017. “Digital Vigilantism as Weaponisation of Visibility.” Philosophy & Technology. 30.

DOI:10.1007/s13347-016-0216-4

Venturini, T., Bounegru, L., Gray, J., & Rogers, R. 2018. “A reality check(list) for digital methods.” New Media & Society, 20(11), 4195–4217.

Wildon, J. 2021. “Twitter / @JordanWildon: Internet sleuthing can be…” September 22, 2021, 01:03 a.m.

https://twitter.com/JordanWildon/status/1440451551949037573?s=20

Yardley E., Thomas L.A.G., Wilson D., & Kelly E. 2018. “What’s the deal with ‘websleuthing’? News media representations of amateur detectives in networked spaces.” Crime Media Cult 14(1):81–109. DOI:10.1177/1741659016674045