The Music Industry’s Latest Anti Capital-ist Movement: A New Form of Communicating Vulnerability and Authenticity

Minimalist typography has been an ongoing trend in online communities for many years, however, as shown by the recent incline in female artists releasing all-lowercase song titles, it has also been adopted into the music industry. The reasons for this movement can be analyzed through the new media paradigms of online vernaculars and digital activism.

Introduction

There is no doubt that the phenomenon that is the internet has instigated various technological and cultural changes in our lives. One of the more surprising transformations has been an aspect that we expected would remain constant throughout any era: the change in the use of typography and evoking emotion through its use. Specifically, the recent trend that involves the use of lowercase typography in the music industry to communicate vulnerability and authenticity. This post analyses the recent trend of using lowercase typography in song titles, the historical context of minimalist typography, the contrast with uppercase typography, and what this means in relation to online vernaculars and digital activism.

The Aesthetics of Lowercase

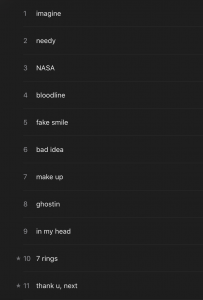

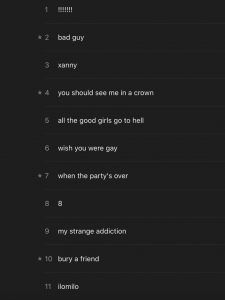

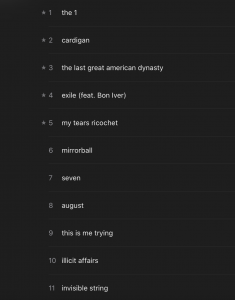

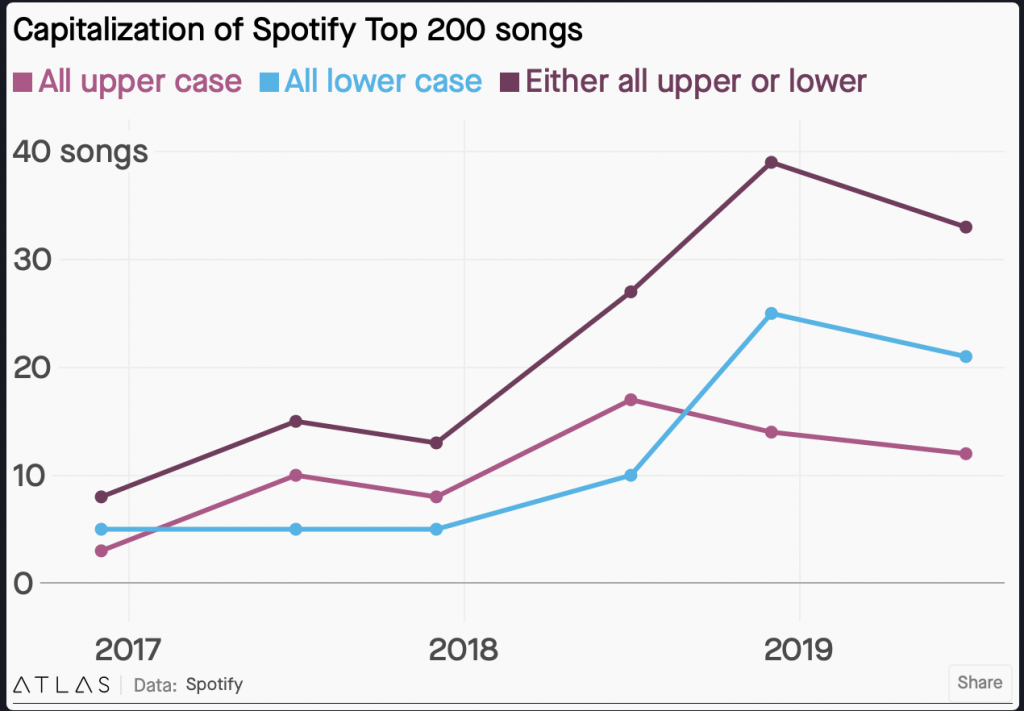

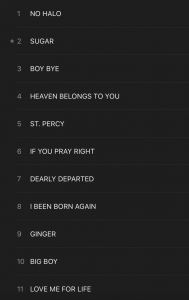

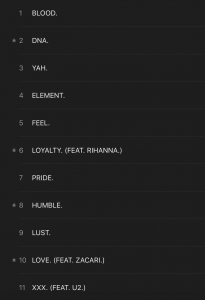

The tendency to use solely lowercase letters for entire albums was recently noticed among female artists who are outspoken about embracing their own definitions of femininity and the feeling of being vulnerable in the public eye. These artists include Ariana Grande with her 2019 album ‘thank u, next’ (see fig.1), Billie Eilish’s 2019 album ‘WHEN WE ALL FALL ASLEEP, WHERE DO WE GO?’ (see fig.2) and Taylor Swift’s 2020 album, ‘folklore’ (see fig 3). According to a study by Quartz that analysed Spotify’s top 200 playlists from 2017 to 2019, songs that have irregular capitalisation have risen from the average of 5 to nearly 40 (Grady). Quartz also found that in 2019, more than 30 songs per week had unusual capitalization (Kopf) (see fig. 4). The reason for this change can be analysed from an emotional perspective. According to internet linguist Gretchen McCulloch, a substantial amount of people “choose minimalist typography deliberately to create a specific effect” (142) and that “stylized verbal incoherence mirrors emotional incoherence” (147). When artists use lowercase, it is a way for them to connect with their fans on a more personal level, embracing their authenticity and displaying their vulnerability as real humans. By using lowercase, artists make themselves more approachable, defusing any hierarchy between themselves and their fans, signalling they do not take themselves too seriously (McCulloch). However, this tactic is not new and has a historical background.

Ariana Grande’s album ‘thank u, next’

Billie Eilish’s album ‘WHEN WE ALL FALL ASLEEP, WHERE DO WE GO?’

Taylor Swift’s album ‘folklore’

Graph retrieved from Quartz showing the capitalization of Spotify Top 200 songs through the years

Historical Context

Using all lowercase typography to convey specific feelings or emotions is something that has recently been popularized in the music industry; but it is not a completely new method of displaying rejection of a conventional way of thinking imbedded in a system. Poet E.E. Cummings was known for using unconventional punctuation and eschewal of capitalization in order to portray an egalitarian spirit, “as if there might be a relationship between upper and lower cases and upper and lower classes” (Muldoon). Another example is bell hooks, who adopted the pen name in order to “draw attention to her work rather than herself” (Mcintyre), because the idea of the late 60s feminist movement was centred around moving away from the individual and towards the works and ideas of people, as a collective (Mcintyre). Hence why lowercase has been widely embraced by the internet, where people are not afraid of expressing their views. Typing in lowercase has become a way of indicating attitude (McCulloch).

Lowercase vs. Uppercase

When we write regular sentences or proper names, we use uppercase, which means we are less exposed to them and become more familiar with the sight of lowercase letters; making us feel psychologically closer to them, which in turn provides feelings of openness and sincerity (Xu et al). Where lowercase is used to indicate familiarity, intimacy and humility (Zimmerman), uppercase is used in situations where attention is needed, such as for emphasis, reminder and warming, where individuals can sense an authoritative tone (Xu et al). The use of lowercase by mostly female artists is not something unexpected. A study on brands found that lowercase is associated with greater femininity and uppercase is associated with masculinity (Wen and Lurie). This idea is proven further when looking at male artists such as Tyler, The Creator (see fig.5), BROCKHAMPTON (see fig.6) and Kendrick Lamar (see fig.7). According to typography experts, the reason for using all uppercase is the visual strength, which projects a bigger persona (Weatherby). As seen with Eilish’s album title, she draws attention with the all-caps cover but contrasts with her lowercase tracks which show more vulnerability. By doing this Eilish becomes more relatable to her audience and makes them feel involved. As this comparison shows, one of the most important functions of lowercase in song titles is for the artists to indicate they belong to a community, alongside their fans (Joho).

Tyler, The Creator’s album ‘IGOR’

BROCKHAMPTON’s album ‘GINGER’

Kendrick Lamar’s album ‘DAMN.’

Online Vernaculars

This sense of belonging to a community by using different typography links to the paradigm of online vernaculars. In their research de Zeeuw and Tuters conceptualize vernaculars as a “group-based discourse, or sociolect, highly innovative of novel forms of expression that are often intentionally obscure to those outside of the in-group” (5). The ecosystems created in connective media are “not simply the sum of individual micro systems but is rather a dynamic infrastructure that shape and is shaped by culture at large” (van Dijck 44). Lowercase users have their own community and talking in particular ways reinforce their networks and sense of belonging (McCulloch). When artists use it, they indicate they relate and understand “how vital it is to be able to convey a typographical tone of voice” (McCulloch 148) and how it has become a way for younger generations to add substance and nuance to their words (Merrilees). Having feminist vernaculars in the media with focus on authenticity and embracing vulnerability can enable marginal agencies to surface and alter hierarchical relations (Coupland) with dominant views that reinforce toxic masculinity.

Digital Activism

Digitally mediated collective action has proven success in communicating “simple political messages directly to outside publics using common digital technologies” (Bennett and Segerberg 742), which emphasizes the importance of using subtle feminism vernaculars to fight toxic masculinity online. Digital feminism can be seen as a self-realising and collective empowerment experience that develops strategies to ensure visibility by appropriating codes of different digital cultures (Jouet), such as using lowercase to express our feelings. Digital activism can lead to undermining communities and break established patterns because of the wide and fast exposure media can give vernaculars (Coupland). Female artists using lowercase can be seen as a form of collaborative and aesthetic creation (Jouet), which sends the message that they are rejecting the conventional ways of writing embedded in a patriarchal system, going on a different path than their male counterparts.

Conclusion

Through this analysis we can see that female artists embracing the subtle vernacular of minimalist typography has a greater significance in the field of digital feminism, by showing that vulnerability is something to be embraced and allowing them to connect with their fans on a more authentic level.

Works Cited

Bennett, W. Lance, and Alexandra Segerberg. “THE LOGIC OF CONNECTIVE ACTION”. Information, Communication & Society, 15.5, (2012): 739-768. Informa UK Limited, doi:10.1080/1369118x.2012.670661. Accessed 23 Sept 2020.

Coupland, Nikolas. “The Mediated Performance of Vernaculars”. Journal of English Linguistics, 37.3, (2009): 284-300. SAGE Publications, doi:10.1177/0075424209341188. Accessed 23 Sept 2020.

de Zeeuw, Daniël, and Marc Tuters. “Teh Internet Is Serious Business”. Cultural Politics, 16.2, (2019): 214-232. Duke University Press, doi:10.1215/17432197-8233406. Accessed 22 Sept 2020.

Grady, Kitty. “Why Everyone on The Internet Uses Lowercase Spelling”. VICE on the Internet, 2020, <https://www.vice.com/en_uk/article/y3z45v/internet-lowercase-spelling-taylor-swift-charli-xcx>. Accessed 20 Sept 2020.

Joho, Jess. “The Surprising Reasons We Turn Off Autocaps And Embrace The Lowercase”. Mashable on the Internet, 2019, <https://mashable.com/article/disable-auto-caps-lowercase-texting-online-communication/?europe=true> Accessed 21 Sept 2020.

Jouet, Josiane. “DIGITAL FEMINISM: QUESTIONING THE RENEWAL OF ACTIVISM”. Journal of Research in Gender Studies, 8.1, (2018): 133. Addleton Academic Publishers, doi:10.22381/jrgs8120187. Accessed 23 Sept 2020.

Kopf, Dan. “The Rise of All-Lowercase and All-Uppercase Song Titles”. Quartz, 2019, <https://qz.com/quartzy/1690992/the-rise-of-the-all-caps-song/>. Accessed 21 Sept 2020.

McCulloch, Gretchen. Because Internet: Understanding How Language Is Changing. Harvill Secker, 2019. ISBN: 9781787302310

Mcintyre, Abby. “Why This Copy Editor Will Capitalize Your Name Whether You Like It or Not”. Slate Magazine on the Internet, 2016, <https://slate.com/human-interest/2016/05/why-do-magazines-like-slate-insist-on-capitalizing-danah-boyd-bell-hooks-and-will-i-am.html>. Accessed 22 Sept 2020.

Merrilees, Kristin. “Why Gen Z Made Capitalization Irrelevant”. Medium, 2019, <https://medium.com/swlh/why-gen-z-made-capitalization-irrelevant-e93f424596bb>. Accessed 20 Sept 2020.

Muldoon, Paul. “Capital Case”. The New Yorker on the Internet, 2014, <https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/03/03/capital-case>. Accessed 21 Sept 2020.

van Dijck, José. The Culture of Connectivity: A Critical History of Social Media. Oxford University Press, 2013.

Weatherby, Tyler. “Type Experts Analyze Ariana Grande’s Upside Down ‘Sweetener,’ Travis Scott’s All-Caps ‘ASTROWORLD’ & More 2018 Stylization”. Billboard on the Internet, 2018, <https://www.billboard.com/articles/events/year-in-music-2018/8491299/ariana-grande-sweetener-travis-scott-astroworld-stylization-interpretation> Accessed 22 Sept 2020.

Wen, Na, and Nicholas Lurie. “The Case for Compatibility: Product Attitudes and Purchase Intentions For Upper Versus Lowercase Brand Names”. Journal of Retailing, 94.4, (2018): 393-407. Elsevier BV, doi:10.1016/j.jretai.2018.10.002. Accessed 22 Sept 2020.

Xu et al. “The Effects of Uppercase and Lowercase Wordmarks on Brand Perceptions”. Marketing Letters, 28.3, (2017): 449-460. Springer Science and Business Media LLC, doi:10.1007/s11002-016-9415-0. Accessed 21 Sept 2020.

Zimmerman, Edith. “13 Reasons We Type in Lowercase”. The Cut on the Internet, 2019, <https://www.thecut.com/2019/02/reasons-to-type-in-lowercase.html>. Accessed 21 Sept 2020.