The Political Ecology of Spotify: How Streaming Takes A Toll On The Environment

Digital music does not just appear out of thin air. While ostensibly immaterial, the energy used to transmit and stream music has a tangible, detrimental impact on the environment. In order to understand Spotify’s role in eco-pollution and e-waste, this blog post aims to debunk the misconception that music digitalized equates to music dematerialized

The Environmental Impact of Spotify

Kyle Devine, a professor at the University of Oslo and recent author of Decomposed: The Political Ecology of Music researches the material forces behind digital music consumption that wreak havoc on the environment.

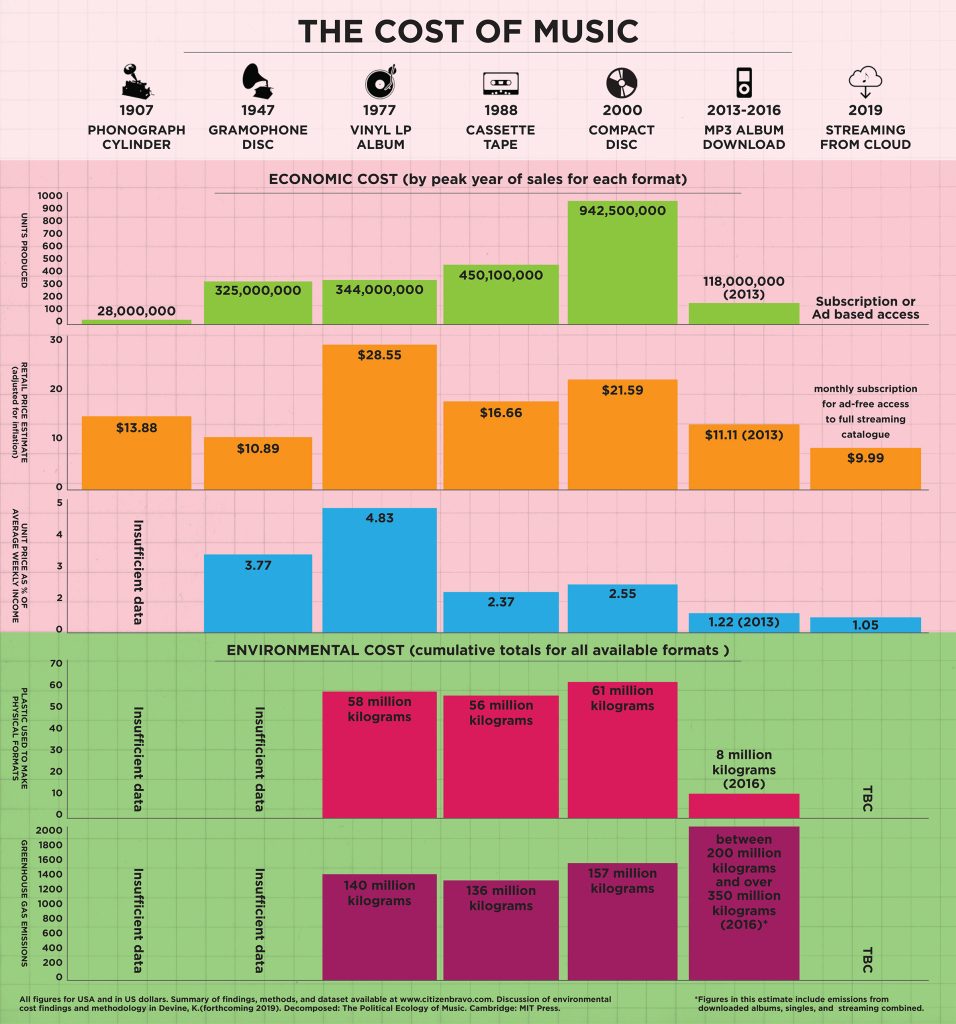

According to a study conducted by Devine in collaboration with Matt Brennan at the University of Glasgow, the greenhouse gas emitted from the energy that powers streaming and downloading music is estimated to be between 200 and 350 million kilograms. This is a sharp increase from the energy used for music consumption in the 2000s, which is approximated to be 157 million kilograms of greenhouse gas equivalents. (Brennan and Devine 52)

As the use of digital streaming continues to rise, the production of plastics used by the US recording industry has dropped down to around 8 million kilograms in 2016, compared to 61 million kilograms in 2000 at the peak of CD sales. (Brennan and Devine 52) This may seem like good news for environmentalists. However, upon closer inspection, the environmental cost of digital music consumption is becoming more evident. The energy it takes to stream and download digital music releases more greenhouse gas by the US recording industry than any other previous format. (Brennan and Devine 45)

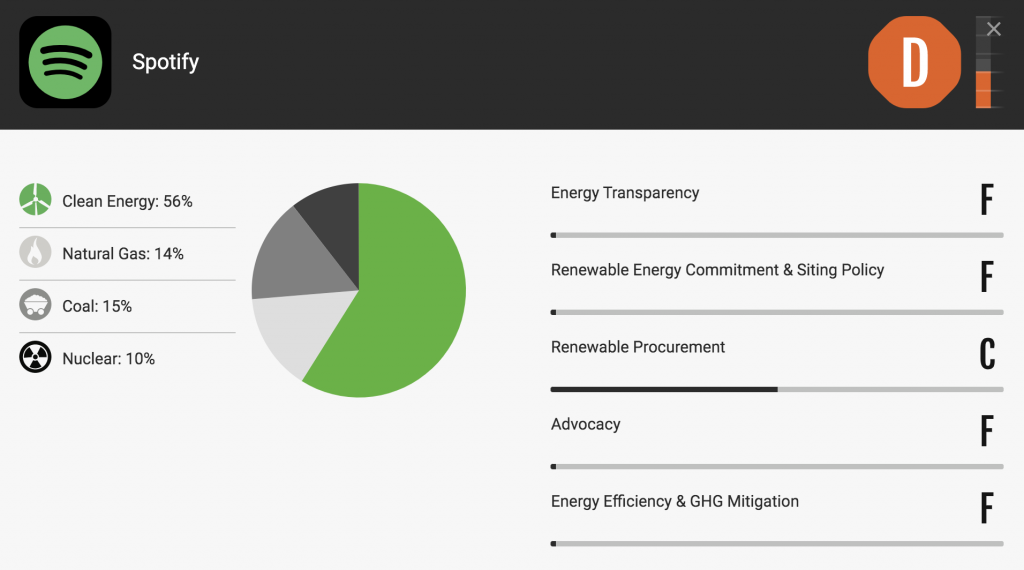

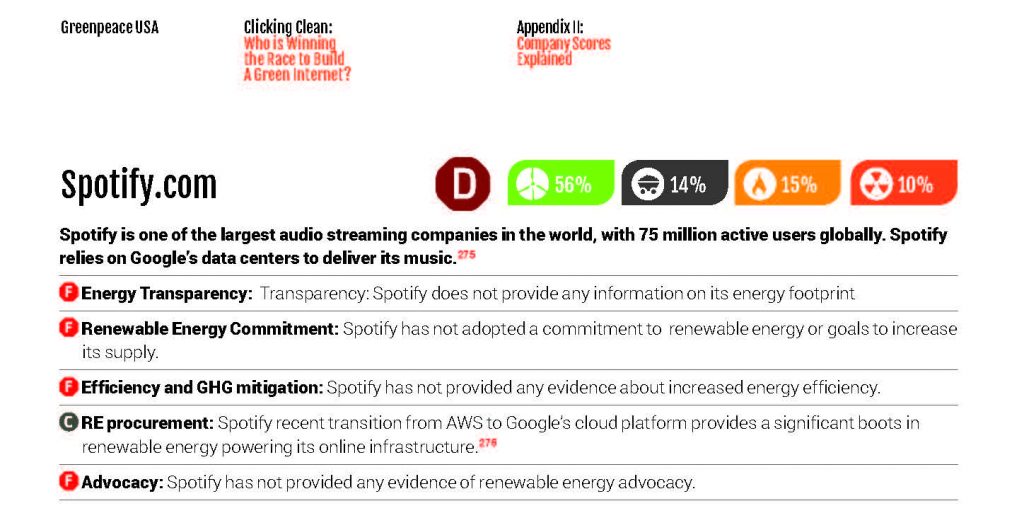

In 2017, Greenpeace’s ClickClean Scorecard tool gave Spotify a D rating. (Ross) Since then, some changes have been made in Spotify’s environmental policies. According to Spotify’s 2019 Sustainability & Social Impact Report, the company has closed down its data center of operations and moved to the Google Cloud Platform (GCP). The report estimates that in 2019 electricity consumption of their Content Delivery Network was 647 MHw, which equates to 173 tonnes of C02. (Spotify, Sustainability & Social Impact Report 2019) Their report claims that Spotify is working to source renewable energy. In other words, Spotify has decommissioned its data centers to transition to the carbon-neutral GCP to reduce its carbon footprint to make the streaming and computing platform more carbon neutral.

However, this dedication to renewable energy is not as clear-cut as it may appear. According to an article in WIRED magazine, when companies such as Google claim to operate entirely on renewable energy, it’s actually a “complicated mix of clean energy generated from their own buildings, renewable power projects they’ve signed long contracts with, and credits or excess power to fill the gaps.” (Kobie) Essentially what companies like Google are doing is purchasing or investing in renewable energy to compensate for the amount of energy already being used. (Ross)

Music as Data

There are two central material components to listening to music as data: delivery infrastructure and accessory hardware. (Devine 380) The digital audio files we listen to rely on a global telecommunications infrastructure that consists of storage and processing facilities as well as transmission and delivery networks. (Brennan and Devine 51) When we stream a track, there is a retrieval and transmission process from network to router to our own electronic devices. (George and McKay) All of this requires energy.

One must also consider the electronics and accessories used to play music—smartphones, headphones, speakers, and computers. These accessory technologies are material devices that are often mined or processed inhumanely and in environmentally damaging ways. For instance, a report from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute reveals how Apple’s supplies in China use displaced Uighurs for their labor. (Hamilton)

The Cloud Is A Factory

While the cloud may appear to be a nebulous, ethereal concept, it is actually a place that exists. Data centers that power the cloud technology and streaming platforms consume vast amounts of energy. In an article published by the Yale School of Environment titled “Energy Hogs: Can World’s Huge Data Centers Be Made More Efficient?” Fred Pearce writes: “Data centers are the factories of the digital age.” (Pearce)

According to a study published on European data centers, the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) sector generates up to 2% of global CO2 emissions. (Avgerinou et. al) This is as much as the airline industry. (Pearce) In Geology of Media, Jussi Parikka writes about similar ideas surrounding data through the lens of medianatures: “Data demand their ecology, one that is not merely a metaphorical technoecology but demonstrates dependence on the climate, the ground, and the energies circulating the environment.” (24)

Greener Ways Of Listening

So, what is the most sustainable way for consumers to listen to music? How ought musicians distribute their recordings in the 21st century? Sharon George and Deirdre McKay propose alternatives for greener listening: if a consumer plans on listening to an album repeatedly, a physical copy is best. Streaming an album over the internet more than 27 times will likely use more energy than it takes to produce and manufacture the same CD. (George and McKay) They also recommend purchasing used vinyl or storing music in local files to reduce the need to stream.

However, this view is not held by all who are aware of the environmental damage caused by streaming. Certain scholars believe that the answer is not in trying to persuade consumers to change their habits or go back traditional media formats––(“It is obvious that returning to CDs, cassettes, or LPs would be unwise given what most people now know about the problems of plastic and petroleum,”)––but instead shifting consumer consciousness to understand the larger context of consumption within a political ecology. (Brennan & Devine, 50)

The Bigger Anthropocene Picture

In Geology of Media, Parikka explores the notion of media materialism, which refers to “the necessity to analyze media technologies as something that are irreducible to what we think of them or even how we use them.” (1) He also writes of medianatures, “there is a double-bind between the relations of media technology and the earth conceived as a dynamic sphere of life that cuts across the organic and non-organic.” (12) These concepts are instructive in understanding the invisible costs of data centers and Cloud technologies to demonstrate that digital does not equate to immaterial. Parikka’s work illuminates how there is always a through-line between digital content and earthly resources.

It’s important for consumers to critically consider the material realities of where their infinite access to media comes from—what raw resources and local economies were involved? Who or what is being exploited? How does our understanding of music relate to the larger Anthropocene era in which we find ourselves?

Works Cited

Avgerinou, Maria, et al. “Trends in Data Centre Energy Consumption under the European Code of Conduct for Data Centre Energy Efficiency.” Energies, vol. 10, no. 10, Sept. 2017, p. 1470. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.3390/en10101470.

Blistein, Jon, and Jon Blistein. “Is Streaming Music Dangerous to the Environment? One Researcher Is Sounding the Alarm.” Rolling Stone, 23 May 2019, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/environmental-impact-streaming-music-835220/.

Brennan, Matt, and Kyle Devine. “The Cost of Music.” Popular Music, vol. 39, no. 1, Cambridge University Press, Feb. 2020, pp. 43–65. Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/S0261143019000552.

Brennan, Matt, and Archibald, Paul. 2019. The economic cost of recorded music: findings, datasets, sources, and methods. Glasgow: University of Glasgow.

Cook, Gary. Clicking Clean: Who Is Winning The Race To Build A Green Internet. Greenpeace, Jan. 2017, p. 102, http://www.clickclean.org/international/en/.

Devine, Kyle. “Decomposed: A Political Ecology of Music.” Popular Music, vol. 34, no. 3, Cambridge University Press, Oct. 2015, pp. 367–89. Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/S026114301500032X.

Hamilton, Isobel Asher. “Apple benefits from forced Uighur labor at its iPhone supplier factories in China, according to an explosive new report.” Business Insider Nederland, 3 Mar. 2020, https://www.businessinsider.nl/apple-forced-uighur-labor-iphone-factory-2020-3/.

Kobie, Nicole. “Apple and Google Are Fighting Climate Change. And Sorta Winning.” Wired UK, May 2019. www.wired.co.uk, https://www.wired.co.uk/article/microsoft-renewable-energy-data-centre.

McKay, Deirdre, and Sharon George. “The Environmental Impact of Music: Digital, Records, CDs Analysed.” The Conversation, http://theconversation.com/the-environmental-impact-of-music-digital-records-cds-analysed-108942. Accessed 26 Sept. 2020.

Music Consumption Has Unintended Economic and Environmental Costs. https://www.gla.ac.uk/news/archiveofnews/2019/april/headline_643297_en.html. Accessed 27 Sept. 2020.

Parikka, Jussi. A Geology of Media. University of Minnesota Press, 2015.

Porter, Jon. “Vinyl and Cassette Sales Saw Double Digit Growth Last Year.” The Verge, 6 Jan. 2019, https://www.theverge.com/2019/1/6/18170624/vinyl-cassette-popularity-revival-2018-sales-growth-cd-decline.

Ross, Alex. “The Hidden Costs of Streaming Music.” The New Yorker, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/the-hidden-costs-of-streaming-music. Accessed 27 Sept. 2020.

Ruser, Vicky Xiuzhong Xu, Danielle Cave, James Leibold, Kelsey Munro, Nathan. Uyghurs for Sale. https://www.aspi.org.au/report/uyghurs-sale. Accessed 27 Sept. 2020.

Spotify, 2019, Sustainability & Social Impact Report, q4live.s22.clientfiles.s3-website-us-east-1.amazonaws.com/540910603/files/doc_downloads/2020/03/Sustainability-Report-2019-FINAL.pdf.