Afghanistan: a mine of big data?

Everything seems to be about (big) data these days, and, as much as there are numerous advantages, we must look at it critically, evaluating their menaces. This subject will be approached raising concern on what is happening with the Afghans’ data collected in the territory over the years.

As pointed out by Gitelman and Jackson[1] in their article, the idea that data is neutral and objective, whose significance is uncertain until translated to current information (Raley 2013) – “raw data” – falls apart when we consider that every piece of information has a background, that frames the information itself. Data aren’t a priori unbiased facts. The historic, social, and cultural circumstances in which data subsist define and delimited the data themselves. Data is neither transparent nor plain, but rather subjective, thus it must be contextually examined. Additionally, data are neither merely numerical nor disaggregate, “They pile up. They are collected in assortments of individual, homologous data entries and are accumulated into larger or smaller data sets.”[2] The power they hold relies on the networks, the intertwined systems they coexist, which conveys in the notion of big data.

Big data is not just about larger quantities of data, but the capability of gathering, examining, aggregating, and directly connecting different datasets (boyd and Crawford 2012), through interdisciplinary fields.

But how did we become so tolerant to this massive collection and third party sharing of our data? Although we won’t be getting in detail here, the ongoing datafication of society takes a role. We can’t pinpoint a precise shift in our mentalities and lives, but we can observe our social interactions being transposed into data (van Dijck 2014). The deep trust in the organizations that dealt with data soon enough was questioned and criticized, as well as their credibility to administer them. To restore trust in the big data sphere, it is necessary to be clear with the standpoints from which data is analyzed, rather than maintaining a neutral claim around them (van Dick 2014).

After the occupation of Afghanistan by U.S forces in 2001, and further establishment of an Afghanistan government, the U.S Department of Defense implemented mechanisms to surveil citizens and used a biometric program together with U.S military operations. The main goal would be to differentiate rebels and terrorists, but soon enough was expanded to a broader number of civilians.

The surveillance systems[3] that collected an undetermined number of biometric data in Afghanistan had a political and historical context, the data weren’t entirely objective in the first place. Besides, these technologic mechanisms communicated through larger databases within the U.S government, corresponding to big data.

“Dataveillance” is the consistent use of high-tech systems to collect data, to track and scrutinize individuals or collectives (Clarke 2017). Modern, sophisticated systems have been implemented to “survey” the world (Gitleman 2013). The operations taking place do not need a central-based system, as different databases are connected and use the same procedures to identify targets, “so that a single unit (an individual or number) can be identified consistently across a range of data sets.”[4]

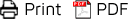

HIIDE (Handheld Interagency Identity Detection Equipment) was one of the dataveillance systems used: it is a portable device that can store up to 22,000 biometric identities scanning iris, fingerprint, and facial recognition. It is entrenched with Microsoft XP, it operates in the field or connected to a PC. It can be customized, adding other features, such as passport reader, keyboard, mouse. HIIDE system can also be used to access greater, centralized databases that accumulate more biometric information.

According to a New Atlas article[5], after collecting biometrics, it decodes the data into binary code and links it to other biographical data. Soldiers could add personal information of Afghans to a U.S. biometric store, claiming its utility in identifying potential threats and in confirming the identity of civilians working with the U.S. military. Biometrics were also used by government departments, as the Independent Election Commission to impede voter fraud during the 2019 parliamentary elections.

This biometric program that led to a wider collection and connection of (big) data was implemented without previous consultation of human rights organizations and the necessary precautions to prevent misuses.

At the U.S withdraw from Afghanistan, and the auto-proclamation of the Taliban administration of the territory, it is questioned what will happen to the biometric data collected over the years. According to security experts[6], the Taliban may not have the necessary equipment to fully exploit HIIDE, but Pakistan could provide the Taliban with all the indispensable means to do so. The re-purposing of data can result in the biometric data – whose dimension no one is certain – being accessed by the entities controlling the State, with other political and security agenda. A surveillance system created for law enforcement purposes can ultimately be used to monitor individuals in arbitrary ways. It is crucial to ponder the potential risks of the data being reused by other entities that pose a threat to others.

Even tough data were collected with an intention and agenda in place, that contextualizes them, – “cooking” the data – it must be emphasized how it is important to create and take advantage of mechanisms that secure them.

It would be cynical to conclude that there are only the negative sides and effects concerning big data, as no binary approach is beneficial. However, big data, as far as maximizes computational technicities, enlarging the collection of datasets and spreading the belief that produces a greater powerful tool of information and knowledge, has its own risks. Corporations, including telecommunication operators and social media platforms, as well as governments and independent organizations must take action to protect data, services, equipment to prevent future damage to their users.

References

Academic readings:

boyd, danah, Crawford, Kate. «CRITICAL QUESTIONS FOR BIG DATA: Provocations for a Cultural, Technological, and Scholarly Phenomenon». Information, Communication & Society 15, no. 5 (2012): 662–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.678878.

Clarke, Roger. «Information Technology and Dataveillance». Communications of the ACM 31, no. 5 (1988): 498–512. https://doi.org/10.1145/42411.42413.

Clarke, Roger. «Dataveillance Regulation.». Accessed 30 September 2021. http://www.rogerclarke.com/DV/DVR.html#C.

Gitelman, Lisa, Jackson, Virgina. 2013. Introduction In « “Raw Data” Is an Oxymoron». edited by: Lisa Gitelman, pp 1-12. Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England: The MIT Press

Railey, Rita. 2013. Dataveillance and Counterveillance In « “Raw Data Is an Oxymoron” », edited by: Lisa Gitelman, pp 121-145.UC Santa Barbara: UC Santa Barbara Previously Published Works

Van Dijck, Jose. «Datafication, Dataism and Dataveillance: Big Data between Scientific Paradigm and Ideology». Surveillance & Society 12, no. 2 (9 de Maio de 2014): 197–208. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v12i2.4776.

Websites’ articles:

Coxworth, Ben. ‘HIIDE Portable Biometric Device Scans Iris, Fingers and Face’. 2010. Accessed 30 September 2021. https://newatlas.com/hiide-portable-biometric-device/15144/.

Klippenstein, Ken, Sirota, Sara. ‘The Taliban Have Seized U.S. Military Biometrics Devices’. The Intercept (blog). 2021. Accessed 30 September 2021. https://theintercept.com/2021/08/17/afghanistan-taliban-military-biometrics/.

Privacy International. ‘Afghanistan: What Now After Two Decades of Building Data-Intensive Systems?’. 19 August 2021. Accessed 30 September 2021. http://privacyinternational.org/news-analysis/4615/afghanistan-what-now-after-two-decades-building-data-intensive-systems.

‘This Is the Real Story of the Afghan Biometric Databases Abandoned to the Taliban | MIT Technology Review’. Accessed 30 September 2021. https://www.technologyreview.com/2021/08/30/1033941/afghanistan-biometric-databases-us-military-40-data-points/.

Figure 1: Getty images

Figure 2: Getty images Figure 3: https://newatlas.com/hiide-portable-biometric-device/15144/#gallery:2?itm_source=newatlas&itm_medium=article-body

[1] Gitelman, Lisa, Jackson, Virgina. 2013. Introduction In “Raw Data” Is an Oxymoron.

[2] Gitelman, Lisa, Jackson, Virgina. 2013. Introduction In “Raw Data” Is an Oxymoron, page 8.

[3] ‘The Taliban Have Seized U.S. Military Biometrics Devices’. The Intercept (blog).

[4] Railey, Rita. 2013. Dataveillance and Counterveillance, in “Raw Data Is an Oxymoron”, page 124.

[5] ‘HIIDE Portable Biometric Device Scans Iris, Fingers and Face’. 2010.

[6] ‘The Taliban Have Seized U.S. Military Biometrics Devices’. The Intercept (blog). 2021