Copyright Infringements: Exploring Fair Use Policies on YouTube

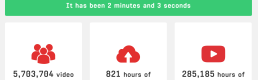

Abstract Copyright infringement and fair use are critical issues for YouTube creators, especially ones who primarily work with content they do not own. This research investigates how copyright is understood and navigated by YouTube creators from the genre of...