Book Review: “Netze und Netzwerke” – by Sebastian Gießmann

In Netze und Netzwerke, Sebastian Gießmann makes a quiet daring attempt to historically map the rise of grids and networks between 1740 and 1840. He views such as not only rising technologies and methods of scientific research, but also as culturally intertwined practices. By means of examining crucial historical moments in which the concepts of networks first began to rise, Gießmann reaches his own limits in establishing a grid between these vast fields. He openly admits so when concluding, “[a]uch alle Geschichten aller Netze’ können nicht anders als ihr Ziel zu verfehlen.” (all histories about all grids are meant to fail their goal“) yet adding that this might be the only way historiography can be realized: by continuously failing to reach the ultimate insight done so through illustration of the subject. (“Vielleicht ist aber nur so noch Historiografie möglich: als fortwährende Verfehlung einer im Dartsellen hergestellten Erkenntnis.“)

Gießmann’s work is an examination of historical developments related to networks and grids in a number of (scientific) fields. He looks closely at the rise of networks as a form of conceptual thinking in sciences such as Biology and Mathematics; he examines the early developments of grid like transportation systems in the 18th and 19th century France; and the ways in which (optical) telegraphs facilitated communication in times of the French Revolution. In doing so, Gießmann takes a sincere attempt to describe the relation between society and technology, claiming that humans form cultural practices around (technological) grids.

As one example he suggests natural scientist George Cuvier whom he regards a pioneer of implementing networks into conceptual scientific thinking. Cuvier, by mapping the natural history of fish, was among the first to put his findings in relation to the broader animal kingdom, establishing an early form of grids. According to Gießmann, Cuvier’s idea of creating connections between up to that point separately examined species, set a milestone in natural sciences and research methods.

Gießmann’s other interest is the history of the French railway system as well as that of the optical telegraph as early formations of networks and grids among transportation and communication systems. Viewed from a political and cultural perspective he explains their evolution towards the beginnings of nowadays prevalent ways of establishing as well as understanding modes of travel and communication. To underline the limitations of such, Gießmann explores the political and social implications that took part in defining the use of technologies.

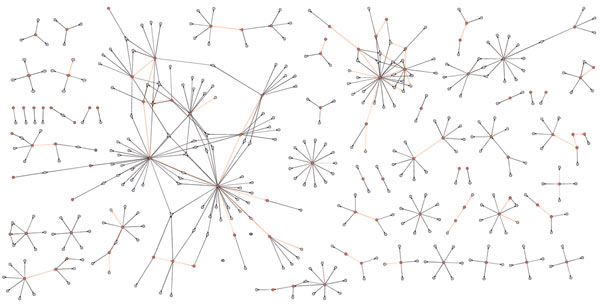

Aside from the abundant historical facts that the reader will find accumulated in this book, Gießmann also centres his attention on more theoretical, almost philosophical attempts to think about networks and grids. By doing so, Gießmann introduces different concepts and termini that have been established in conceptualizing and understanding the workings of networks. He strongly underlines the immense complexity that researchers are dealing with and challenges the reader to think about new ways of approaching this field. According to Gießmann, historical research of networks must in itself happen through the establishments of networks to share knowledge and thought. In doing so, he introduces his website as part the book and the research process. Unfortunately, the website is only available in German.

From the beginning, Gießmann makes clear that no finite explanations about network theory and network history can be presented. Instead he can only give glimpses into this vast net of knowledge, notions, theories and thoughts. Regrettably, it is only in the last chapter that he actually addresses this problem. Even though Gießmann’s focus clearly lies in the history of the subject, it would have been interesting to explore that point more elaborately. Even if done from a philosophical standpoint.

While it is significant to understand the historical context and the way it manifests itself in the development of networks and grids, it is particularly crucial to seek alternative ways of thinking about networks to perhaps better grasp their wholeness. With the Internet having an almost Godlike presence, this challenge has taken the subject of networks and grids, as a matter to connect and correlate, to another level.

Networking capacities have been exceeded beyond what is possible to imagine. Perhaps therefore new ways of thinking about networks and grids have become necessary. Is it even crucial to think in terms of such? Why is network research important and what are we hoping to learn from it? Is admitting their sheer presence not enough? Why the need to understand the mechanism itself and not just their ramifications? And is it possible to understand one without the other?

Gießmann does a good job in tackling those questions, passively rather than actively. By going back some 300 years in history he shows the great importance of networks and grids as part of how knowledge, science, politics, transportation, communication and many other matters of human life have developed. This inevitably points to the question of where these developments will lead us in the future.

Full details:

Netze und Netzwerke. Archäologie einer Kulturtechnik, 1740-1840

Netze und Netzwerke. Archäologie einer Kulturtechnik, 1740-1840

by Sebastian Grießmann, 2006

transcript Verlag, Bielefeld

ISBN 3-89942-438-7