Sciencemappr: Trying to unleash the hypertextual potential of the Web

Last week I already pointed out the amazing significance and potential of the Internet to organize, structure and index all knowledge gathered across the globe. Rather than an indirect library of indexes and references, the web is equipped with the possibility to reference directly and instantly. This takes care of both the physical as well as the psychological issues that arise when trying to index the entire human knowledge pool.

However, as I also touched upon in the piece from last week, there is the idea that the web, as a hypertextual result of a desire to document links between scholarly pieces, there is a great sense of information overload. As Nicholas Carr describes in his piece “is google making us stupid”, there has been a change in the character of reading and studying because of the linked character of the web. Carr describes this idea mostly as a personal observation of himself, being unable to focus on books for longer than a few minutes because one is constantly distracted by other media that share the same screen and links.

Conversely, and also more concretely, there has been research into the different ways people actually read hypertexts by the use of eye capturing software (Protopsaltis and Bouki, 2005). They discovered two main ways different users read different hypertexts – to make things clear: the distinction was connected to both the users as well as the texts, not either/or. Some texts were read in a linear fashion and the links followed in the order they were presented, while other articles were first scanned more superficially and then read in a more random order, depending on the interests of the user.

This kind of research could be interpreted in order to confirm the idea that hypertext is read differently than traditional texts but when one considers – for example – reference books, scholarly supplements or even traditional encyclopaedias, this distinction becomes wholly unbalanced (Blustein, 2000). In those types of writings it is essential that one skips certain parts and/or reads it in a discontinuous fashion. All of a sudden the Hypertext and the Web become the very texts themselves: linked, noded and networked paths: Barthes’ “ideal text” (Barthes, 1970). Landow explains:

“Scholarly articles situate themselves within a field of relations, most of which the print medium keeps out of sight and relatively difficult to follow, because in print technology the referenced (or linked) materials lie spatially distant from the references to them. Electronic hypertext, in contrast, makes individual references easy to follow and the entire field of interconnections obvious and easy to navigate. Changing the ease with which one can orient oneself within such a context and pursue individual references radically changes both the experience of reading and ultimately the nature of that which is read”(1992).

In other words; the hypertextual character of the web makes it the ultimate “ideal text” when concerning referenced and cited scholarly work.

We thus find ourselves in a situation with at one point the idea of an ideal text that, at the same time, doesn’t coincide with a well recognised reality that Nicholas Carr describes. An example: When doing scholarly research on Google Scholar, one day I found an article on innovation, but when queried on the Web: 4084 citations. Now how can one find something that is of additional interest to ones research? This “ideal” text will simply not do without some extra layer of information that will help someone in her or his search. A long story short: The current hypertext of the web lacks something to make it live up to its promises. Foucault wrote:

“frontiers of a book are never clear-cut, […] it is caught up in a system of references to other books, other texts, other sentences: it is a node within a network . . .(a) network of references” (1974).

I argue that the same goes the web when science is concerned. With only the citations the links are there, but the nodes and their positions and relations to one another are unclear or even non-existent: The network is simply not a network yet.

In this respect a datavisualisation project can do a lot of good. There have been a number of projects that already tried to do something in this respect. One example is Science-Metrix’ Onthology Explorer:

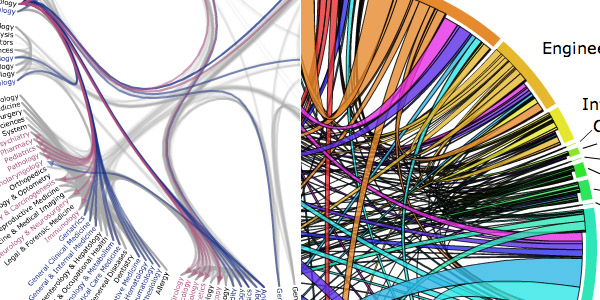

The Onthology Explorer seems to recognise the importance of linking and the visual aid that is necessary to gain some insight into the connections between domains and scientific fields. Their “map of science” is particularly interesting in that respect because it visualises which debates might be going on between different scientific disciplines and what theories are – perhaps unexpectedly – relevant to those fields. It also emphasises the idea that knowledge should be structured in a less taxonomic manner, as new disciplines can arise when others start cooperating and hybridising. By using a visualisation such as this one, such a field could defend its own existence in a more folksonomic kind of way.

The Onthology Explorer seems to recognise the importance of linking and the visual aid that is necessary to gain some insight into the connections between domains and scientific fields. Their “map of science” is particularly interesting in that respect because it visualises which debates might be going on between different scientific disciplines and what theories are – perhaps unexpectedly – relevant to those fields. It also emphasises the idea that knowledge should be structured in a less taxonomic manner, as new disciplines can arise when others start cooperating and hybridising. By using a visualisation such as this one, such a field could defend its own existence in a more folksonomic kind of way.

Still, the Onthology Explorer leaves out a very important aspect and problem previously discussed: It doesn’t supplement us with any advice of where to look for new answers concerning problems. In leaving out the original texts, titles and their references to one another, the Onthology Explorer remains a nice visualisation with very little to offer on a more practical scale.

Another example is the Citations Explorer incorporated within the ISI Web of Knowledge. As the WoK consists of an enormous database of texts and references they should have the ability to map the entire scientific field but, as I already mentioned in the last article, it lacks basic functionalities in every respect.

First of all, one can only query one text and the visualisation takes 5 minutes to load so there is no quick scanning and selecting involved in the way the Protopsaltis and Bouki research mentioned before describe. Every time a new text is selected, a new network has to be loaded and that can’t be the character of something that is literally called the WEB of Knowledge. Another problem that arises is that there is no connectivity visible between the referenced texts, their fields or any other form of background. Basically, the WoK Citation Explorer is a list of references that the user can order in a certain way, but without the ability to extract much information that might be valuable for continuing one’s research.

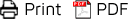

With these ideas in mind, my group and I started working on a visualisation that will incorporate the links texts have, as well as the secondary information that might link those texts to others. On a geographically structured map we try to combine the interesting observations found in the Onthology Explorer – concerning cross-referencing research fields and such – with the ones that are lacking in the WoK’s Citation Explorer.

(Click here and here for a video of our testing session in the eye tracking lab)

By using the historical, geographical, disciplinal and institutional variables of every text we thus try to map the different ways texts are connected to one another. This visual aid that lacks in a list of citations will be provided to the user who might be able to, once again, see the forest through the trees. The visual layer we provide should help the Web gain some ground in reaching the great expectations people like Landow had of it in 1992 and perhaps one day, might still achieve.

References

Barthes, Roland. (1974). S/Z. Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1970. S/Z. Translated by Richard Miller. New York: Hill and Wang.

Blustein, J. (2000). “Automatically generated hypertext versions of scholarly articles and their evaluation. Proceedings of the Eleventh ACM Conference on Hypertext and Hypermedia”, 201-210. Retrieved September 26, 2011, from http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/336296.336364

Carr, Nicholars. (2008). “Is Google Making us Stupid?”. The Atlantic Magazine. Boston.

Foucault, Michel. (1976). The Archeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language. Translated by A. M. Sheridan Smith. New York: Harper & Row.

Landow, G. P. (1992). Hypertext: The convergence of contemporary critical theory and technology. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Protopsaltis, A., & Bouki, V. (2005). “Towards a hypertext reading/comprehension model. Proceedings of the 23rd annual international conference on design of communication: Documenting & designing for pervasive information”. Retrieved April 26, 2011, from http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/1085313.1085349