From Chocolate Chips to Online – Creating a Cookie Monster

Project by: Daniël Landman, Nick van der Meulen, Nicola Romagnoli and Seastar So.

Link to Final Project.

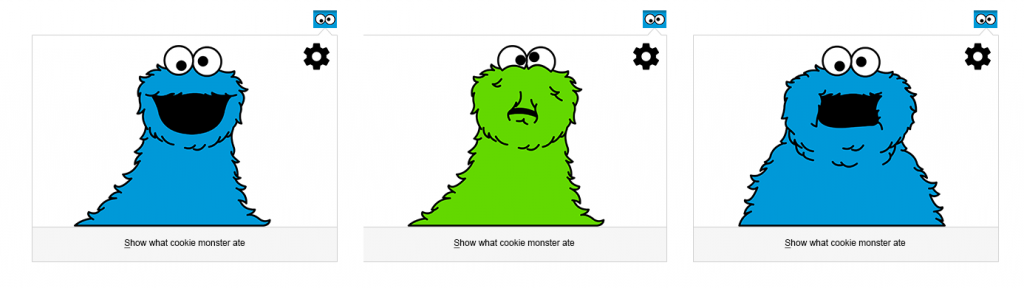

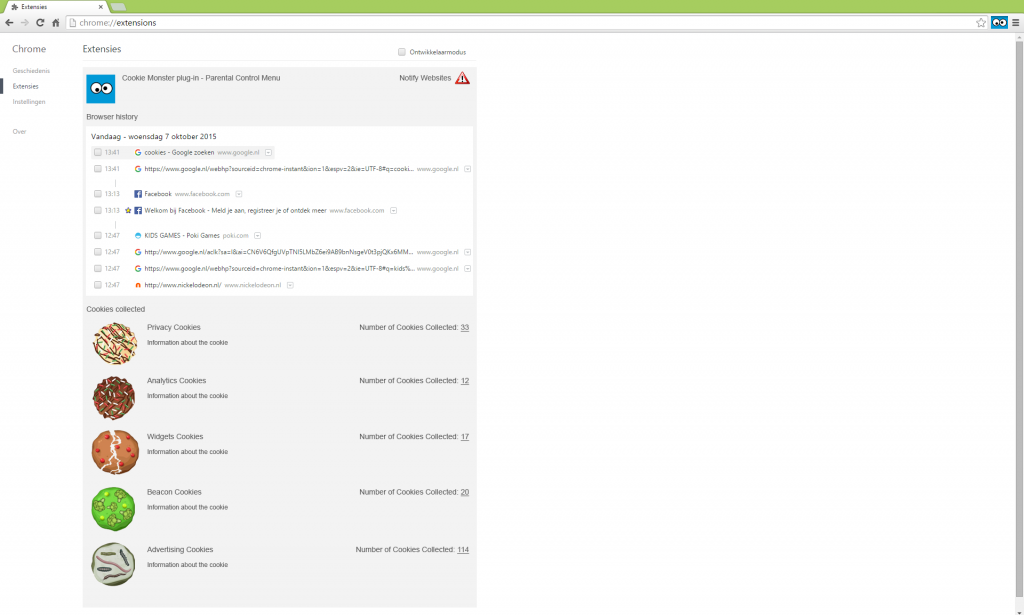

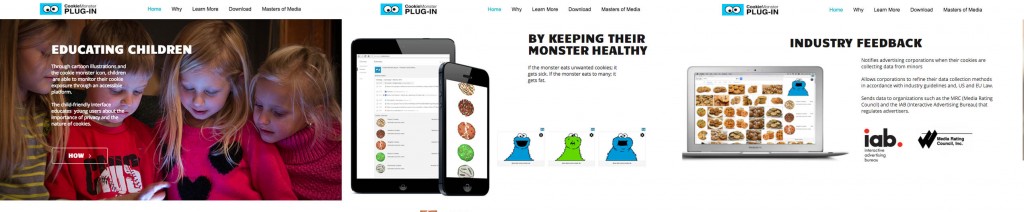

Cookies are the most well-known form of online tracking and can be used for a variety of reasons such as recording personal website preferences, understanding online user behavior and perhaps the most controversial, for managing the advertising you see on a website (Geary). Our Cookie Monster browser plug-in is designed to intervene within online browser practices of children, creating awareness amongst children under the age of twelve by teaching them about their browsing behavior through collection of unwanted cookies and other tackers they encounter online. In addition, the Cookie Monster browser plug-in provides the distributors of cookies and other trackers with a feedback mechanism which notifies that a child under the age of twelve is browsing the web.

Protecting children’s privacy and online presence has always been a highly debated topic in our society (Allen; Youn; Wang, Lee, and Wang). In the past, concerns were more focused on inappropriate exposure to violence and sexual content on the Internet and possible exploitation of children by adult predators (Allen 756). However in recent years, the focus has shifted to data protection and consumer privacy (Wang, Lee, and Wang; Roesner, Kohno, and Wetherall; Post). As one report conducted by VG Technologies reported, “More than 90% of children under the age of twelve have a digital footprint – an online presence such as photos and other personal identifiable information” (Post). It is also explained that unregulated advertisements can not only influence purchasing decisions, but also manipulate children in their media consumption habits (O’Keeffe and Clarke-Pearson 802).

A recent report by the Global Privacy Enforcement Network, which examined 1,500 sites and apps that targeted or were popular with children, concluded that two-thirds of websites collected children’s personal information (Lomas). Furthermore, only 31% of sites/apps had controls that limited the collection of personal information from children, and 50% of them shared this personal information with third parties (Lomas). These reports raise important concerns regarding the increasing presence of children online, the development of highly sophisticated cookies and trackers as well as the legal ambiguity surrounding online advertising, data collection policy, and consumer privacy.

As found in many other western countries, industry regulation is the current approach to monitoring online advertisements (EPRSLibrary). For example, in the Netherlands, the De Nederlandse Reclame Code (The Dutch Advertising Code), regulates child and youth advertising in media. However, the NRC currently only regulates youth advertising in traditional media such as TV and their online presence and enforcement remains unclear and ambiguous (NRC). In the United States, legislations such as COPPA (Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act) aim to make it more difficult for websites to collect personal data directly from young children without a parent’s knowledge and consent (Allen 758). In response to the changing technology and internet culture, legislators are now trying to renew the Act and pass a Do Not Track Kids Act, which would further extend existing protections for youth and children (London, Seiver, and Thompson).

Cookie Monster is designed to directly intervene in the vacant space left by government and private interests and offers a concrete solution that addresses children, parents and corporations. Cookie Monsters facilitates media education and privacy education both educating both parents and children, and urges corporations and media companies to review their privacy policy and data collection processes.

For more information about the function and usage of the Cookie Monster plug-in please visit our plug-in launch website. http://bit.ly/CookieMonsterApp

For more information about the function and usage of the Cookie Monster plug-in please visit our plug-in launch website. http://bit.ly/CookieMonsterApp

Who are involved?

- Children

The use of new media technologies has been a concern for parents, educators and the governments around the globe, and has increased the cultural attention around media literacy (Buckingham et al.; Lee). The idea of media literacy is “the ability to access, understand and create communications in a variety of contexts” (Buckingham et al. 5). In the design of the Cookie Monster, we based our idea on one of the mainstream approaches of media education — the conceptual approach of “inoculation” ( Lee 3). This is a protective education approach that stresses the need to protect younglings by “arousing their awareness of the potential dangers” they might encounter (Lee 4).

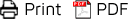

Cookie Monster visually represents a child’s online behaviour and is based on the kind and amount of cookies he consumes. This child-friendly interface allows the platform to remain accessible to children, while also providing important information.

- Parents

Parents influence a child’s growth and development. Therefore consideration regarding a child’s behavior must include parental authority in its methodology. Numerous research projects suggest that parental involvement is an important role in developing children’s media literacy (Buckingham et al. 38). Cookie Monster is designed to allow parents to monitor online browser history, as well as the cookies children encounter throughout their sessions through a secure login. Most importantly, Cookie Monster also functions as an educational platform, informing parents of the presence and function of online trackers through informative packages and periodic newsletters.

- Corporations

According to the report by the Global Privacy Enforcement Network, their research discovered that many organizations whose sites/apps were popular with children also engaged in data collection (Lomas). The report stated that companies simply “claimed in their privacy notices that they [data collection cookies] were not intended for children, and then implemented no further controls to protect against the collection of personal data from the children who would inevitably access the app or site” (Lomas). This makes us question the problematic means of acquiring “consent” from users, and the advertising-centered business culture in the digital economy.

Here, Cookie Monster introduces a feedback mechanism that mediates between user and software. The plugin communicates with advertising corporations, notifying them when their cookies are collecting data of minors and allowing them the opportunity to refine their data collection methods in accordance with industry guidelines and, US and EU Law. Cookie Monster also sends data to organizations such as the MRC (Media Rating Council) and the IAB (Interactive Advertising Bureau) that regulates advertisers (Marshall).

The Cookie Monster is not only a response to the public debate of the legal ambiguity and lack of regulation surrounding online advertising, data collection policy, and consumer privacy, but also answers the raising concern of media literacy and education of young children and social responsibility of websites and corporations in the academic community. One concern however is the increasing responsibility thrust upon consumers to individually safeguard against potential risks online. Strong governmentality and legislation remains a critical component of maintaining a fair and accessible internet, especially given the complex and sophisticated developments of technology and its interaction with society. Cookie Monster initiates this discourse, but further government collaboration must follow. This original idea hopes to tackle not only in a technical aspect by blocking cookies and reporting problematic websites, but also with an educational function that leads to change in perception and awareness among the public.

References

Allen, Anita L. “Minor Distractions: Children, Privacy and E-Commerce.” Houston Law Review 38 (2001): 751–776.

Buckingham, David et al. The Media Literacy of Children and Young People: A Review of the Research Literature. London: Ofcom, 2005. eprints.ioe.ac.uk. 9 Oct. 2015.

EPRSLibrary. “Protection of Minors in the Media Environment. EU Regulatory Mechanisms.” European Parliamentary Research Service. N.p., n.d. 18 Sept. 2015.

<http://epthinktank.eu/2013/03/27/protection-of-minors-in-the-media-environment-eu-regulatory-mechanisms/>.

Geary, Joanna. “Tracking the Trackers: What Are Cookies? An Introduction to Web Tracking.” The Guardian 23 Apr. 2012. The Guardian. 17 Sept. 2015

<http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2012/apr/23/cookies-and-web-tracking-intro>

Ghostery. “About Ghostery”. Ghostery. 2015. 17 Sept. 2015. <https://www.ghostery.com/en/about-us/company-history/>

Lee, Alice Y. L. “Media Education: Definitions, Approaches and Development around the Globe.” New Horizons in Education 58.3 (2010): 1–13.

Lomas, Natasha. “Privacy Concerns Raised Over Kids’ Apps And Websites.” TechCrunch 3 Sept. 2015. 18 Sept. 2015.

London, Ronald, John D. Seiver, and Bryan Thompson. “Significant Amendments to COPPA Proposed in Do Not Track Kids Act.” Privacy & Security Law Blog. N.p., 22 June 2015. 9 Oct. 2015. <http://www.privsecblog.com/2015/06/articles/marketing-and-consumer-privacy/significant-amendments-to-coppa-proposed-in-do-not-track-kids-act>

Marshall, Jack. “Marketers Push Back on MRC Ad Viewability Standards.” N.p., 25 Feb. 2015. 15 Oct. 2015.

< http://blogs.wsj.com/cmo/2015/02/25/are-online-ad-viewability-standards-failing>

NRC. “Kinderen op internet doelwit van reclame.” 16 Sept. 2008. NRC. 10 Oct. 2014. <http://www.nrc.nl/next/2008/09/16/kinderen-op-internet-doelwit-van-reclame-11607434>

O’Keeffe, Gwenn Schurgin, and Kathleen Clarke-Pearson. “The Impact of Social Media on Children, Adolescents, and Families.” Pediatrics 127.4 (2011): 800–804. pediatrics.aappublications.org. 10 Oct. 2015.

Post, Rachael. “Friend or Foe? The Rise of Online Advertising Aimed at Kids.” The Guardian 28 Feb. 2014. The Guardian. 10 Oct. 2015.

Roesner, Franziska, Tadayoshi Kohno, and David Wetherall. “Detecting and Defending Against Third-Party Tracking on the Web.” N.p., 2012. www.usenix.org. 10 Oct. 2015.

Wang, Huaiqing, Matthew K. O. Lee, and Chen Wang. “Consumer Privacy Concerns About Internet Marketing.” Commun. ACM 41.3 (1998): 63–70. ACM Digital Library. 9 Oct. 2015.

Youn, Seounmi. “Determinants of Online Privacy Concern and Its Influence on Privacy Protection Behaviors Among Young Adolescents.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 43.3 (2009): 389–418. Wiley Online Library. 18 Sept. 2015.