Are You Ready To Get Tinderized?*

How Are You Looking Online Today?

Looking for a date but too shy to approach anyone face-to-face? Lucky for you, the market for smartphone apps that connects people from a distance is rapidly extending. One of those apps is Tinder. Using your Facebook profile, this app allows you to “find out who likes you nearby” and opens a way for new connections.

As we will argue, Tinder can be seen as an example of the merge of offline and online identities that seems to be one of the main strands of arguments in academic studies on online representations right now. On the other hand, however, Tinder shows how the possibility of a full merge can also be questioned.

How does it work?

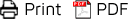

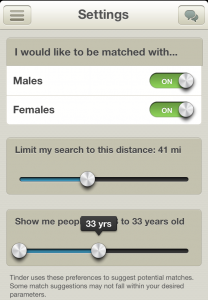

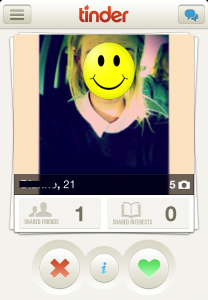

Tinder uses your Facebook account to subtract information for your Tinder profile. Upon installing it, the app asks you to login with your Facebook account, which it then uses to index your age, gender, friends and interests. In addition, Tinder takes your profile picture from Facebook and uses it as the image for your Tinder account. The second step consists of filling in your own preferences. Tinder allows for matches to be found on the basis of gender (are you looking for men, women or both), vicinity (0-100 miles) and age (18 – 50+). In combination with the location Tinder gets from your smartphone’s GPS-signal, the app loads a list of possible matches in your vicinity. You can go through these profiles, either liking or dismissing the people on your screen by respectively clicking on the “heart” button or the “cross”. An option for more information is also available. Once one of the people you showed interest in likes you back, Tinder gives you the option to chat with that person in the app’s interface, opening up the possibility for an actual conversation that would eventually lead to an encounter.

Breaking Through The Online/Offline Opposition?

Tinder can be placed in a list of online initiatives that use user-generated profiles to find people you like. However, Tinder can also be conceptualized in a different way than conventional online dating platforms. There seems to be a shift from seeing offline and online self-representations as separated from each other, to an increasingly merged idea of online and offline identity.

In the early days of online dating, people that participated in online dating through websites were often perceived as people that would not be able to function on a social level in real-life. For this reason, dating sites were often studied mainly for the level of anonymity they offered. ((For instance, the degree in which profile pictures corresponded with an offline identity was a field of interest (Hancock and Toma). )) Nowadays, however, the way apps like Tinder engage with online (re)presentations of identity gives way for a deconstruction of such a strict online/offline dichotomy. Recently, one of the main focuses of academic studies seems to be on the way online environments are increasingly starting to resemble offline environments. As Patti Valkenburg argues:

By now, the Internet is so widely used that the online population increasingly resembles the offline population. As a result, patterns that occur in the offline world also increasingly emerge in online life. (852)

Online dating through a location-based app like Tinder, also referred to as “Satellite Dating” (Quiroz), has shifted traditional desktop dating to mobile dating. In this way Tinder could be perceived as an online representation of our presence.

Furthermore, because Tinder uses Facebook to provide basic information, a double self-representation is created. As scholars Eran Toch and Inbal Levi argue, “Facebook works similarly to a private home, regulated by relatively tight social norms and observance” (547). This means that the types of interaction on Tinder differ from more conventional online dating platforms and even other mobile dating applications such as such as Scout, SayHi, Badoo and Grindr. The information that is available on Facebook is meant for social interaction and not specifically for dating. In the video below you can find more information on how Tinder distinguishes itself from traditional dating solutions:

However, Tinder also shows the limitations of seeing the offline/online dichotomy as obsolete, because it still uses certain formats in which a user can express their identity. For instance, Tinder seems to be open to people with all sorts of sexual/gender orientations, yet still uses established, somewhat conventional, notions of sexuality/gender. The app relies heavily on Facebook’s framework to establish the gender of its users. More importantly, Facebook at least allows users that do not identify themselves as male or female to check the “other” box when listing their gender, whereas Tinder ignores this option for one’s own profile or in one’s preferences. The app asks if you are looking for male, female or both, but does not think outside of this box, possibly excluding those of us that do not identify with the conventional notions of gender and sexuality.

In conclusion, aside from some limitations, Tinder can be perceived as a progressive app on the dating market, offering a dating experience to different kinds of people and taking into account the blurred boundaries between online and offline interactions. ((Want to read more on Tinder? Here is an article from our Masters of Media blog that compares male and female perspectives on Tinder.))

*”Are You Ready To Get Tinderized” is a slogan used by Tinder in the promotion of their application and therefore property of gotinder.com. More about Tinder could be found on Tinder.

References

Hancock, Jeffrey T., and Catalina L. Toma. “Putting Your Best Face Forward: The Accuracy of Online Dating Photographs.” Journal of Communication 59.2 (2009): 367–386. Wiley Online Library. Web. 6 Oct. 2013.

Quiroz, Pamela Anne. “From Finding the Perfect Love Online to Satellite Dating and ‘Loving-the-One-You’re Near’: A Look at Grindr, Skout, Plenty of Fish, Meet Moi, Zoosk and Assisted Serendipity”. Humanity & Society 37.2 (2013): 181-185. Sage Journals. Web. 6 Oct. 2013.

Toch, Eran, and Inbal Levi. “Locality and Privacy in People-Nearby Applications.” Toch Research Group at Tel Aviv University. Web. 6 Oct. 2013.